Editor’s Note: David Gelles is CNN’s executive producer of political and special events programming. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

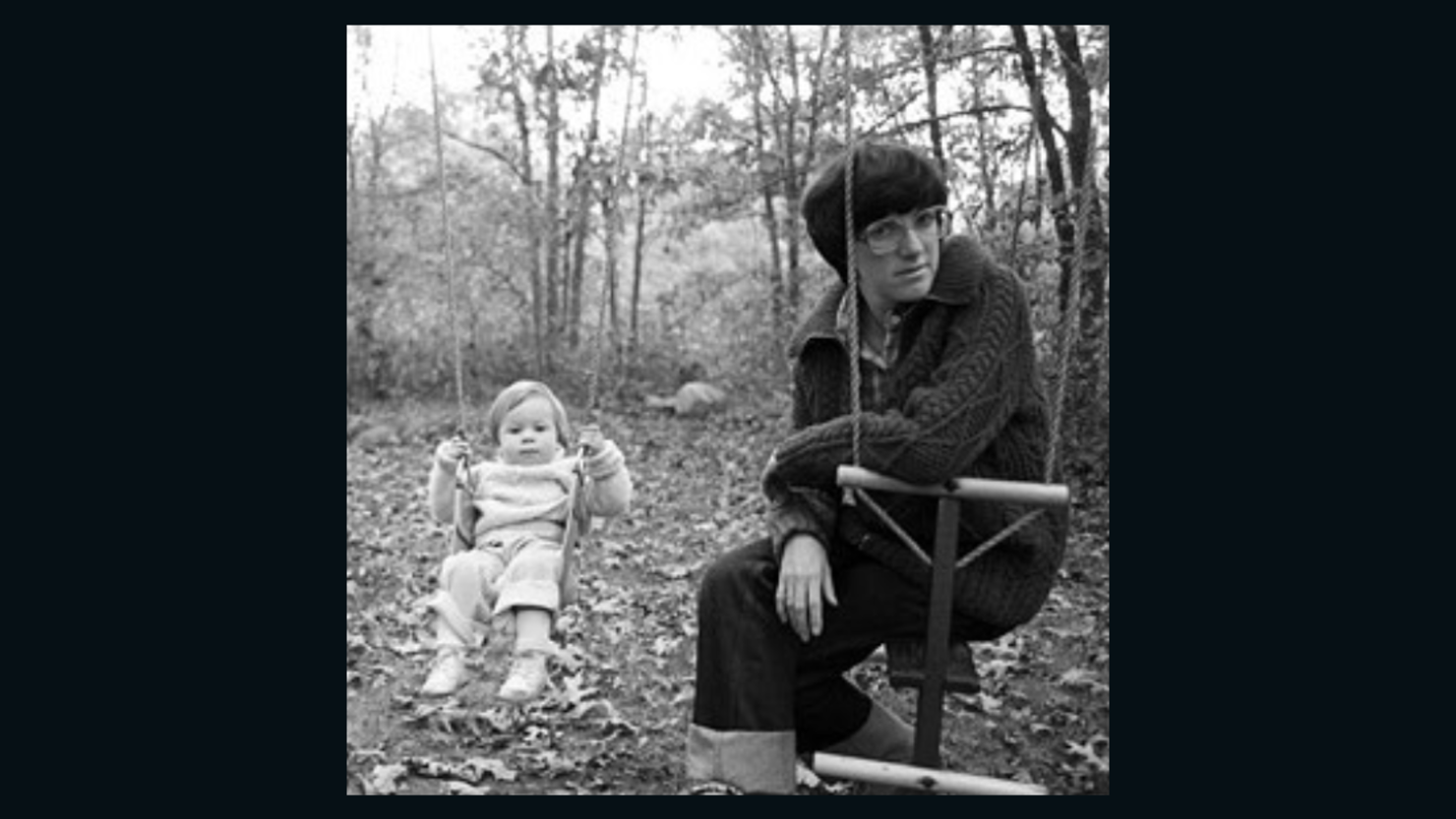

For the past 10 months I had been planning my father’s eulogy. I was rehearsing lines in my head, jotting down ideas when they came to me, trying to perfect it, so it would be just right for when the moment came. But in a cruel twist of events I was forced to write a eulogy for my mother with less than 24 hours’ notice.

It was my dad who was dying of brain cancer, but it was my mom who was now dead. And as the country was shutting down and canceling events because of coronavirus, I was now planning a funeral.

I always imagined my mom’s funeral would be when she was in her late 90s. After all, my grandmother lived until she was 97 – and pretty much outlived every one of her friends. She had good genes, everyone in the family had said.

My mother was just 75, younger than some presidential candidates, and still had dozens of friends who wanted to attend her funeral. But Saturday, in the hours after she died, hours after I watched her take her last breath, I was furiously texting her friends and saying, please don’t come to her funeral.

The synagogue was closed. The funeral home was closed, and we could do only a graveside service. On top of everything, my father was in failing health and social distancing was an imperative.

I promised everyone we would hold a fitting memorial service when we made it out of Covid-19’s wake. But it wasn’t any comfort to me or them. Social distancing, while an important step to slowing the spread of the virus, has deepened the pain of what my family and I have lost.

Instead, we gathered in the 48-degree windy March weather with a dozen family members and a rabbi as we said goodbye. We had a minyan (a gathering of 10 required for Jewish prayer), but barely. There were no hugs. No kisses.

As we partook in the Jewish ritual of shoveling dirt on the grave, the rabbi noted that not everyone may want to touch the handle of the shovel. Some just used their bare hands to help spread dirt on the casket.

After the funeral, I awkwardly elbow bumped the rabbi and we returned home to our quarantined quarters. Traditionally, Jews gather together in the home of the bereaved family and sit shiva. My earliest memory of a sitting shiva was after my grandfather died. I was 8. For seven days I hung out in my grandfather’s living room eating cookies as the smell of smoked fish hung in the air.

Now, in 2020, with coronavirus panic setting in, I consulted with my parents’ rabbi, who agreed we couldn’t have anyone come back to the house. The principle in Jewish law of pikuach nefesh, or the idea that preserving a human life overrides any strict religious rules, applied here – and so we could not gather a large crowd to grieve together.

There were just nine of us in the house after the funeral that day – my mother’s sister, her husband, and their daughter joined my father, my older brother, my wife and I, and our two kids.

Just like so many of the events playing out on cable news in 2020, it felt surreal. And, as I sat there, I could not help but replay the horrible chain of events that had transpired in the previous 24 hours.

I had gone to bed Friday night worried that if my mother died of coronavirus, I would become the sole caretaker for my father, who has terminal brain cancer.

The call came Saturday morning from the hospital. My mother was in the ICU and had been declared brain dead. The doctor told me she had suffered a ruptured brain aneurysm, and it was a non-recoverable event.

Early Friday, my mother had taken my father to the same hospital for a radiation treatment. When the procedure was over, my mother texted me. I texted back, “Great. Wash your hands.” I was freaked out over the thought of my mother being in a hospital and somehow catching Covid-19.

Friday night, my father’s doctor called to tell me they discovered more tumor growth in the most recent scan, and he had only one to six months to live. I called my mother, and she was distraught. She cried.

At midnight, my mom said she had a headache and asked my father to call an ambulance. By the time she got to the ER, she could no longer talk or breathe on her own. The same neurosurgeon who had treated my father hours earlier was called in to evaluate my mother.

My mom had been caring for my father around the clock since his diagnosis last June. I did everything I could to help her, but she took on the challenges of around-the-clock care. She told me there were many times when it was just too much to handle.

The doctors wouldn’t confirm it, but I’m convinced my mother died because she couldn’t bear to live without my father.

Everything has changed, people keep saying about living life with Covid-19 under lockdown and quarantine. But, in my particular case, it has made the sudden loss of my mother much more painful.