Editor’s Note: Kate Maltby is a broadcaster and columnist in the United Kingdom on issues of culture and politics, and a theater critic for The Guardian newspaper. She is also completing a doctorate in Renaissance literature. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

Before Hilary Mantel turned her attention to 16th-century English statesman Thomas Cromwell, the subject of her 2009 novel ‘Wolf Hall,’ the British novelist had long been preoccupied with ghosts.

On the first page of her memoir ‘Giving Up The Ghost,’ she writes of catching a glimpse of her deceased stepfather on the stair – this is nothing unusual, she tells us, because “I am used to seeing things that ‘aren’t there.’” The chief ghost who haunts that memoir is ‘Catriona’, Mantel’s imagined daughter; not merely unborn, but unconceived. Mantel underwent an emergency hysterectomy at the age of 27, devastating her body and wrecking her chance of children. She writes eloquently about the ghost nature of fantasy families, the phantoms who inhabit the lives we dream for ourselves.

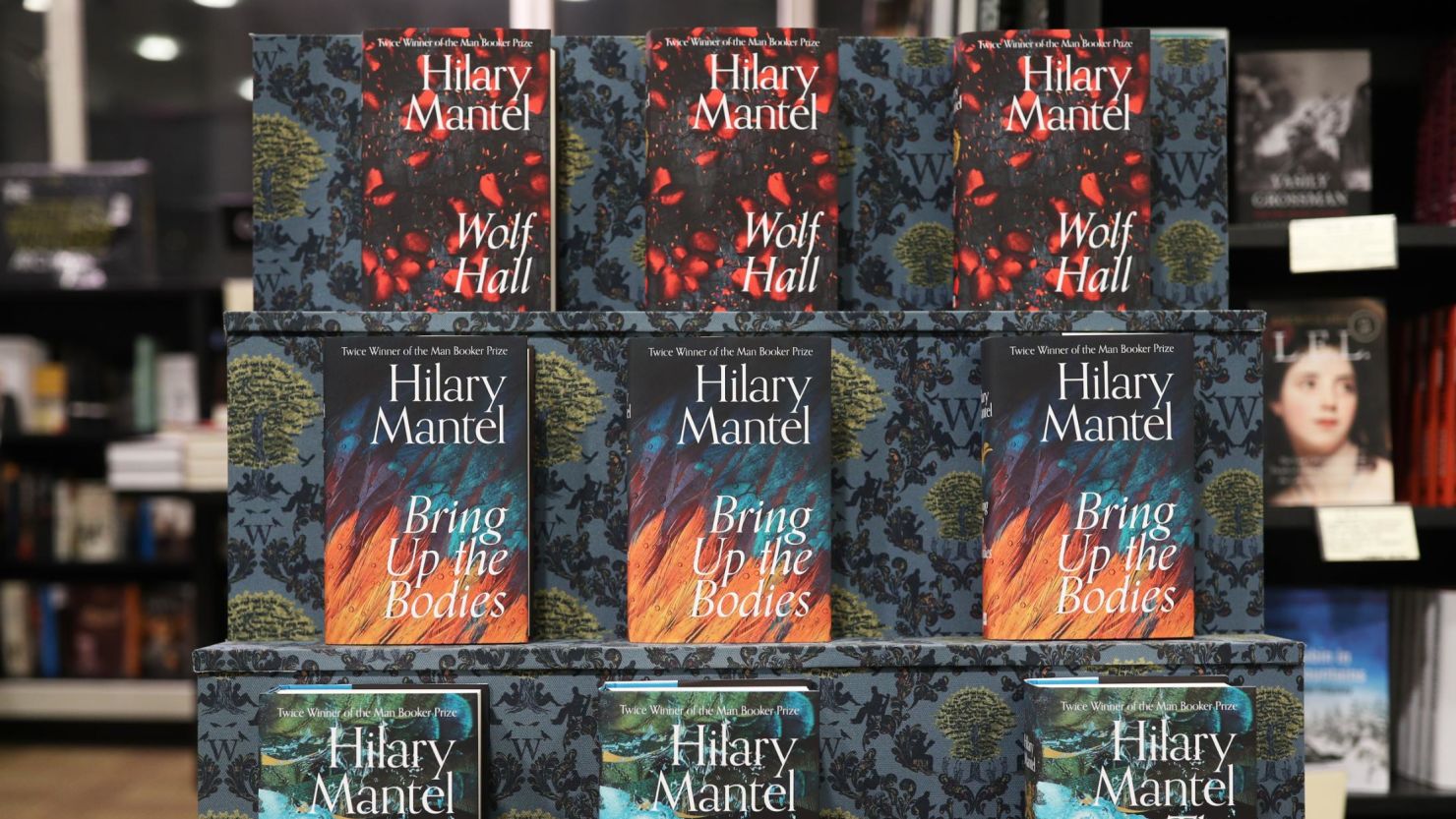

‘Wolf Hall,’ which traced the early life of Henry VIII’s most competent minister, was followed in 2012 by ‘Bring Up The Bodies.’ Between them, the two novels have sold over 5 million copies worldwide. The last in the trilogy, ‘The Mirror and The Light,’ has just been published. Read all three together, and you realize we have been reading ghost stories all along.

‘The Mirror and the Light’ is an accomplishment in multiple forms at once: an expression of Mantel’s advanced academic understanding of Tudor history; a poetic homage to the literary culture of the period; a theological meditation on the eschatology of a Christian soul; a Faust tale of damnation; a feminist cry against ways in which women have historically been bought and sold. But above all, it is an innovation in the ghost story.

The mind of Thomas Cromwell

Throughout this trilogy, we have traveled inside the consciousness of Thomas Cromwell. The real Cromwell was a brewer’s son who became a lawyer and later right-hand man to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the English churchman who failed to facilitate Henry VIII’s divorce from Katherine of Aragon. When Wolsey fell from Henry’s favor, Cromwell took over, administering the country for Henry and nudging him towards a Protestant reformation of the English church. But establishing the Church of England meant conflict with the orthodox Catholic Thomas More (the antagonist of Book 1). Keeping up with the capricious Henry, a king haunted by his own miscarried sons and fear of impotence, meant disposing of Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn (the antagonist of Book 2.)

Mantel exaggerates the poverty of Cromwell’s childhood and gives him a drunken, abusive father. She also invents a childhood rivalry with More, with Cromwell a boy servant at the elite institute at which More is educated. Childhood injustices matter to Mantel: “I don’t know if there is a case on record of a child of seven murdering a schoolteacher,” she writes in her own memoir, “but I think there ought to be.”

Cromwell, as Mantel presents him, has always been a man who lives his dreams, memories and metaphors all at once. Like Mantel, he is haunted by lost daughters. The first words of ‘Bring Up The Bodies’ suggest their blood-stained ghosts. “His children are falling from the sky. He watches from horseback; acres of England stretching behind him: they drop, gilt-winged, each with a blood-filled gaze.” Only later does Mantel enlighten the reader: Cromwell is watching the flight of two hunting-hawks, named for those dead daughters.

This opening is typical of Mantel’s prose. It uses the present tense. It constructs a third person voice which feels like the first person. The prose in ‘The Mirror and The Light’ is a little less opaque, its nuances a little less subtle. So is Cromwell himself: a Faust-figure much closer to damnation than the equivocating humanist of the earlier books. His sins are no longer deniable. Neither are the family ghosts. His dead children appear to him; so does his old protector Wolsey. So do his executed foes. Thomas More is always there. (“Nothing ended with his death. It only began.”) Anne Boleyn and her alleged lovers. (Were any of them guilty? asks a servant. Cromwell avoids the question.) Even a rival boy from Cromwell’s childhood. These are intimate enemies, more familiar than family.

The ‘Wolf Hall’ trilogy will endure as one of the extraordinary literary achievements of our lifetime. Judged by that standard, The ‘Mirror and The Light’ is a worthy conclusion, even if the first two volumes have jaded the critical eye and attuned us to the odd flaw. At nearly 900 pages, it is too long. Hilary Mantel should feel no need to prove her historical expertise by now, but she drifts at times too deep into extensive technical descriptions, digressions on how the Tudor nobility feasted or how their king costed the construction of his warships. She has always had a knack for ekphrasis, the technique of describing a work of art within a work of art. But in ‘Wolf Hall’ her hero’s voice always inhered to his descriptions: in ‘The Mirror and the Light’ we don’t always hear him there.

The pacing is dangerously uneven. The content covers the historical period between Anne Boleyn’s execution in May 1536 and the end of Thomas Cromwell’s career: it is surely no spoiler to note that the historical Cromwell was executed for treason in July 1540. But Mantel, like so many of us, is overly interested in the blockbuster elements of the Tudor soap-opera. Henry VIII’s marriage to Jane Seymour lasted just over a year but takes up the book’s first 520 pages. From then on, we rush headlong through the last stand of the Pilgrimage of Grace (a conservative rebellion in the Catholic-sympathizing North in 1536); Cromwell’s fight to ensure Protestant continuity after the death of Anne Boleyn; the arrangement and failure of Henry’s unconsummated marriage to Anne of Cleves; and eventually the downfall of Cromwell himself. The rush allows Mantel to capture the precipitate nature of Cromwell’s fall. But the upshot is that the reader is sometimes left feeling short-changed. Even a doorstopper of a novel like ‘The Mirror and the Light’ can be made to feel flimsy.

How much of this is truly history?

Yet even in the most frantic passages, Hilary Mantel has done her research. Annotations from the real Cromwell’s correspondence, still preserved in English archives, pop up throughout the text. Here is Cromwell’s notorious to-do list of judicial brutality: ‘the Abbot of Reading to be tried and executed’. (“He has seen the evidence and the indictments; there is no doubt of the verdict, so why pretend there is?”) Cromwell’s hand-scrawled final letter to the king when his own turn comes: ‘I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy.’

The scholarship of Diarmaid MacCulloch, Cromwell’s recent biographer and Mantel’s friend, leaves its fingerprints all over ‘The Mirror of the Light.’ This is a Cromwell busy with plans for re-draining England’s river system and sewer-drainage, and for an efficient new census system. (Both aspects are highlighted in MacCulloch’s work.) It is a Cromwell, too, who knows how to use a nationwide network of cousins (for who in Tudor England can one trust, but blood?)

How much of this is truly history? When I asked MacCulloch, he told me: “The England of ‘Wolf Hall’ is not exactly Tudor England, but a parallel universe based on her profound understanding, just as Philip Pullman’s Oxford (in the sci-fi series ‘His Dark Materials’) is not actual present-day Oxford, but is inconceivable without that actual present-day Oxford.” For Mantel’s own view of history-writing, we get a clue in one of her first novels, ‘A Place of Greater Safety,’ which takes the French Revolution as its setting. The year is 1774, the omniscient narrator tells us. “Everything that happens now will happen in the light of history. It is not a midday luminary, but a corpse-candle to the intellect; at best it is a second-hand lunar light, error-breeding, sand-blind and parched.” A ‘corpse-candle’ is a ghostly light that appears at hauntings in folklore, often lighting the way to a graveyard. This is Mantel’s idea of history: another ghost-story, always intimating our own mortality.

In ‘The Mirror and the Light,’ death brings neither clarity or reconciliation. “The dead wander the lanes of the next life like strangers lost in Venice,” Cromwell reckons. “Even if they met, what would they have to talk about?” One is reminded of Mantel’s 2005 novel, ‘Beyond Black,’ which introduces us to a suburban psychic named Alison. Alison reassures her clients that they will meet their loved ones again, but knows in her heart that “in fact, the chances are about the same as meeting somebody you know at a main-line station at rush hour. It’s not 14 million to one, like the National Lottery, but you have to take into account that the dead, like the living, sometimes like to dodge and weave.” In Mantel’s stories, human souls dodge and weave around each other, unwilling to make eye-contact whether living or dead.

Death stalks women, in particular. So precarious is the act of childbirth in the Tudor universe that, as Mantel reminds us, “a pregnant woman will usually not stand godmother to another woman’s child, as she deems her future too precarious.” She knows she may die: “if she is prudent, she settles her affairs.” This may all seem very Tudor in its barbarism, but Mantel burns with anger in her own memoir when she describes how male doctors in the 1970s refused until too late to take her symptoms of endometriosis seriously, forcing her ‘mangled’ hysterectomy. In ‘A Place of Greater Safety,’ 18th-century women endure similar fates while their husbands settle matters of state: one woman dies in childbirth after being told that “English overcoats,” or rudimentary condoms, “are not things that married men will entertain.”

The same feminist anger burns here, beneath the descriptions of Jane Seymour’s preparations for childbirth. “Whereas we bless an old soldier and give him alms, pitying his blind and limbless state, we do not make heroes of women mangled in the struggle to give birth. If she seems so injured that she can have no more children, we commiserate with her husband.” Four hundred years later, Mantel had found herself wrestling with the same concerns. Would her husband leave her after her hysterectomy? “When women apes have their wombs removed, and are returned by their keepers to the community, their mates sense it and desert them.” The Tudor court; the London of the 1970s; an zoo of apes: it all comes down to wombs in the end.

Why these books haunt us

Where there is beauty in ‘The Mirror and The Light,’ it is usually found in poetry. Mantel is clearly familiar with the poetry of Thomas Wyatt, and with ‘The Devonshire Manuscript,’ a multi-authored collection of love poems scribbled by courtiers of Anne Boleyn in a single manuscript. Chris Stamatakis, Lecturer at University College London and a Wyatt expert, told me that in her “exhaustive, meticulous research into the historical record,” Mantel has throughout this trilogy managed to mimic the destablizing nature of the period’s poetry, where “interior selves are hard to disentangle from their external projections, from the dialogue and gossip of unreliable intermediaries, and are only half-glimpsed through their speakers’ precarious memories.”

The most vivid characters in the ‘Wolf Hall’ trilogy are, as Stamatakis put it, “half-glimpsed.” For much of Wolf Hall we barely meet Anne Boleyn, but we hear about her constantly – we see the negative space around her. (This why the television adaptation of the novel, which insisted on showing us Claire Foy’s cruel and simplistic Anne Boleyn instead of letting us imagine her in multiple second-hand versions, was less successful.)

If there is a charismatic figure of the same weight as ‘Wolf Hall”s Boleyn in ‘The Mirror and the Light’ it is the exiled William Tyndale, translator of the Bible into English, hero to hard-line Protestants, but anathema to Henry VIII because he refused to assist in his divorce from Katherine of Aragon. We never meet him. We hear many versions of his story. The single chapter in which we come to understand Tyndale’s fate, titled ‘The Bleach Fields,’ is the most powerful piece of writing I have read in years. To say a single word more is to spoil it.

Mantel, descended from Irish Catholic immigrants to England and educated by nuns she loathed, does not deliver a version of events that will please Roman Catholic readers. Relics are exposed as forgeries, monks as usurers. Her Thomas More – canonized in 1935 and glorified by Robert Bolt’s 1960 play, ‘A Man For All Seasons’ – is in Mantel’s telling a bloodthirsty theocrat, a biblical fundamentalist. (“He would chain you up, for a mistranslation. He would, for a difference in your Greek, kill you.”) But as the More scholar Joanne Paul reminded me, post-war historians disagreed. Geoffrey Elton notoriously labelled More “a sex-maniac;” for Jasper Ridley he was a blood-thirsty “fanatic.” If Mantel’s reading is ‘anti-Catholic’, so too is the research of a generation of scholars. Richard Marius’s ‘Thomas More: A Biography’ is well worth reading for those who want to see where Mantel draws her sources.

Mantel’s Cromwell appears first in Wolf Hall as More’s liberal, ethical foil. But if she imagines More in hell, there is enough evidence in ‘The Mirror and The Light’ to damn Cromwell, too. In ‘A Place of Greater Safety,’ Mantel averts her eyes before her revolutionary heroes reach the guillotine: “There is a point beyond which – convention and imagination dictate – we cannot go; perhaps it is here, when the carts decant onto the scaffold their freight, now living and breathing flesh, soon to be dead meat.” In ‘The Mirror and The Light’ she has no such qualms: we inhabit Cromwell’s consciousness even as the first inconclusive blows of the axe fall. (The axe is blunt: Cromwell of course, notes that he would have arranged his own execution more efficiently.) Only then can we follow him no further. But this being a ghost story, he will haunt us.