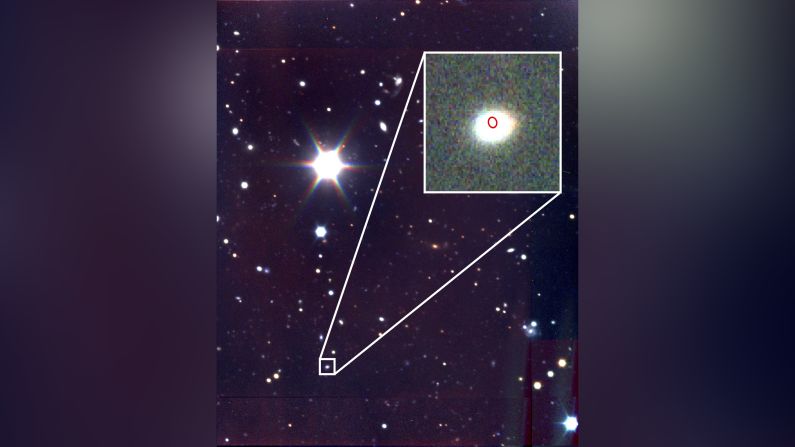

When stars behave strangely, astronomers take notice. In the case of a star known as HD74423, it was amateur astronomers who first spotted the anomaly in data captured by NASA’s latest planet-hunting space satellite TESS. What they didn’t realize was that they were looking at an entirely unknown type of star – the first of its kind.

This star of interest, located about 1,500 light-years from Earth, was flagged to the astronomy community – but astronomers didn’t understand it either.

“What first caught my attention was the fact it was a chemically peculiar star,” said Simon Murphy, study co-author and postdoctoral researcher from the Sydney Institute for Astronomy at the University of Sydney. “Stars like this are usually fairly rich with metals – but this is metal poor, making it a rare type of hot star.”

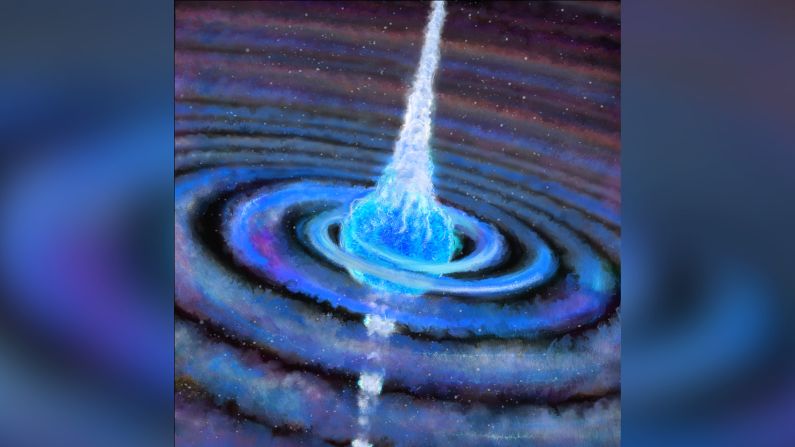

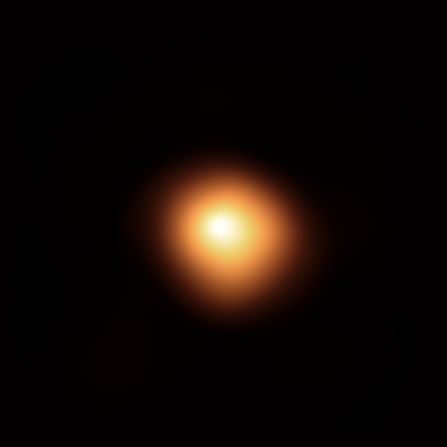

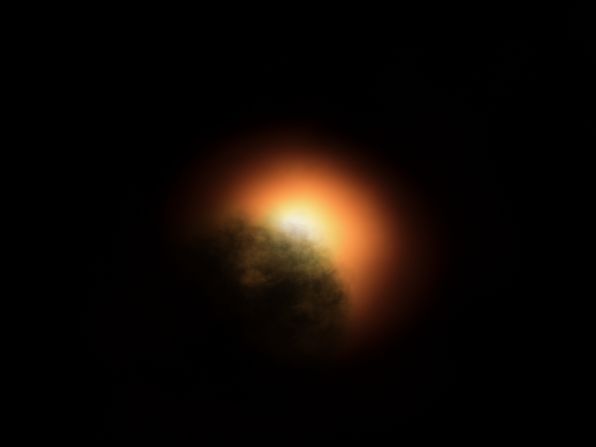

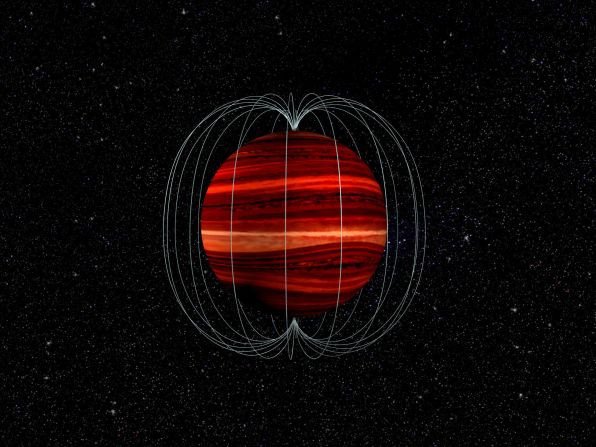

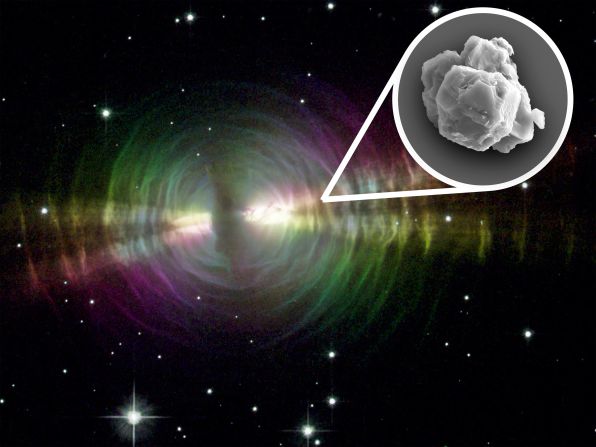

The star is about 1.7 times the mass of our sun. And they saw it pulsating – but just on one side of the star, a heartbeat blinking at us from a great distance.

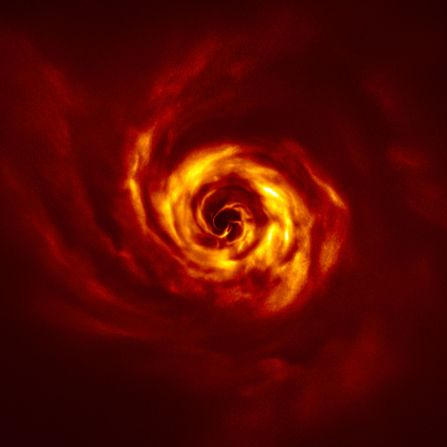

Stars are known to pulsate, and even our sun exhibits this kind of activity due to hot gas churning beneath the surface, causing oscillations.

No matter the age of the star or how long or short these oscillations last, all pulsating stars are usually similar in that the pulsating can be seen on all sides of the star.

Until now, that is.

This new star only appears to be pulsating in one hemisphere of its surface.

“We’ve known theoretically that stars like this should exist since the 1980s,” said Don Kurtz, study co-author and inaugural Hunstead Distinguished Visitor at the University of Sydney from the University of Central Lancashire in Britain. “I’ve been looking for a star like this for nearly 40 years and now we have finally found one.”

The study published Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

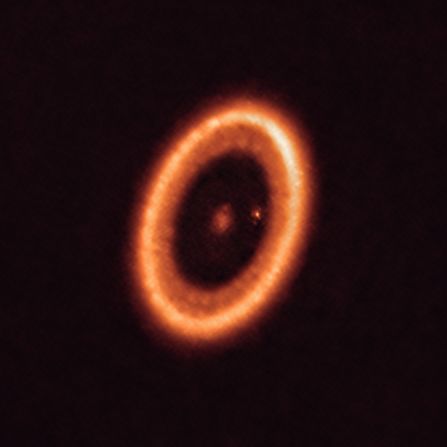

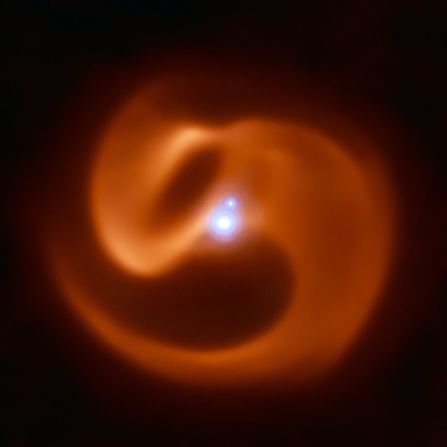

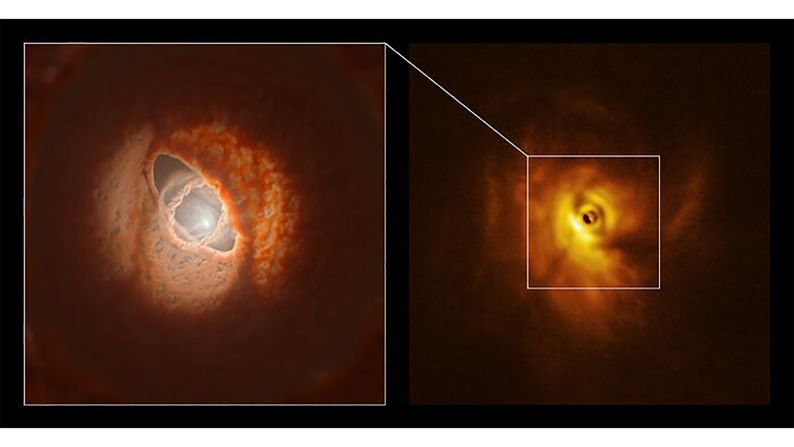

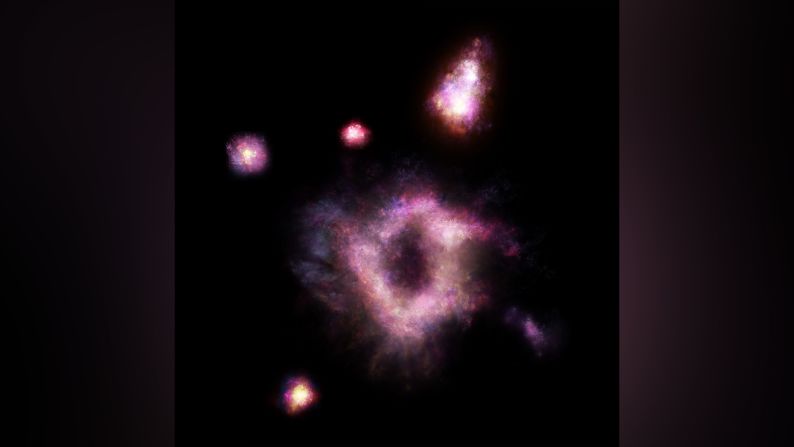

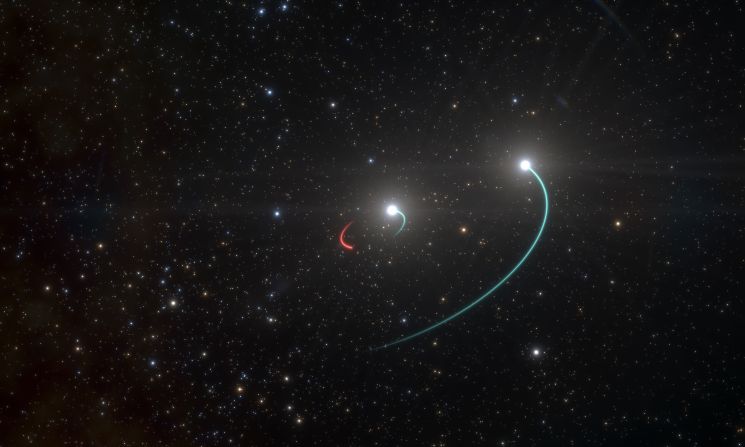

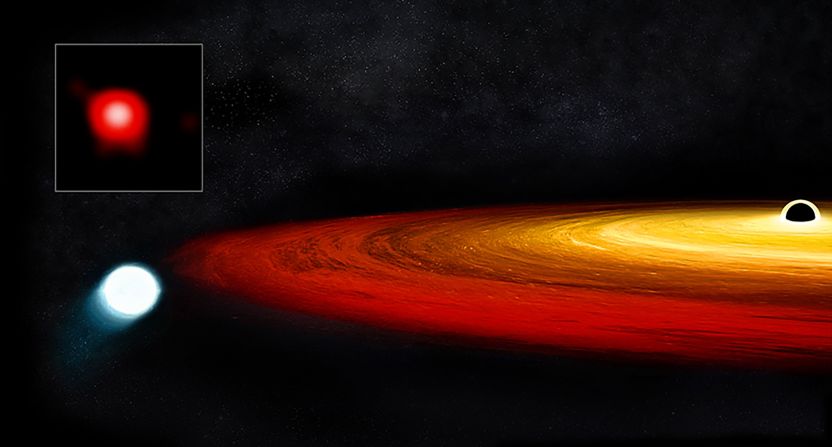

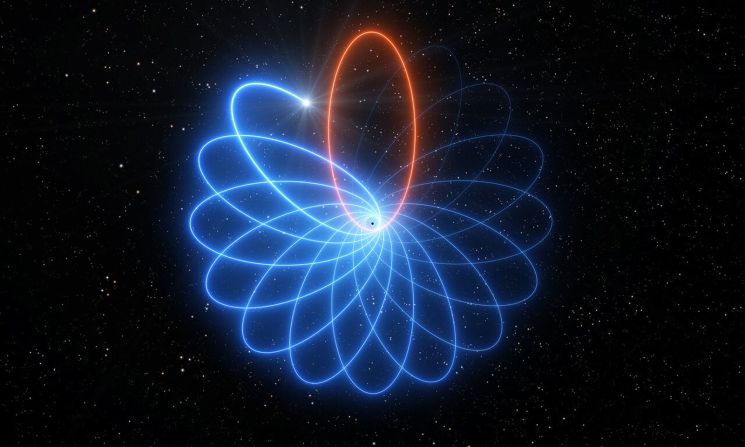

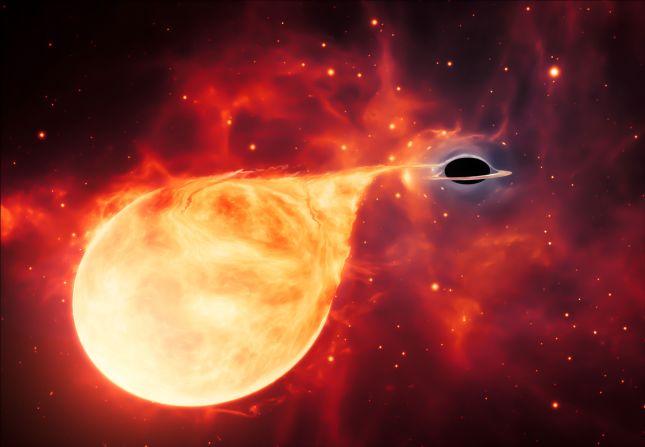

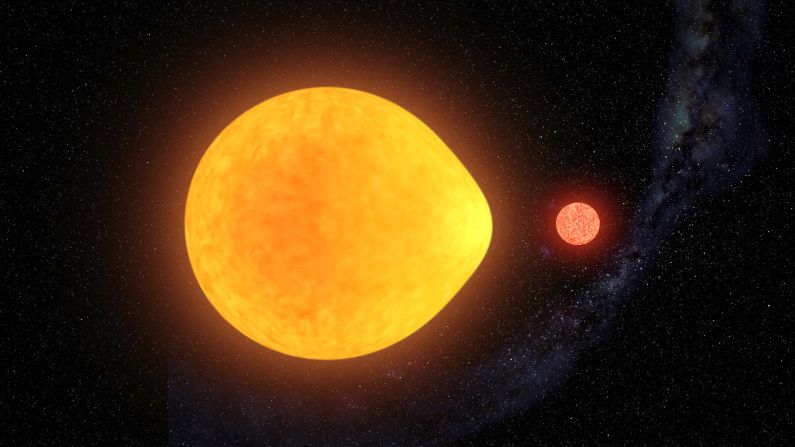

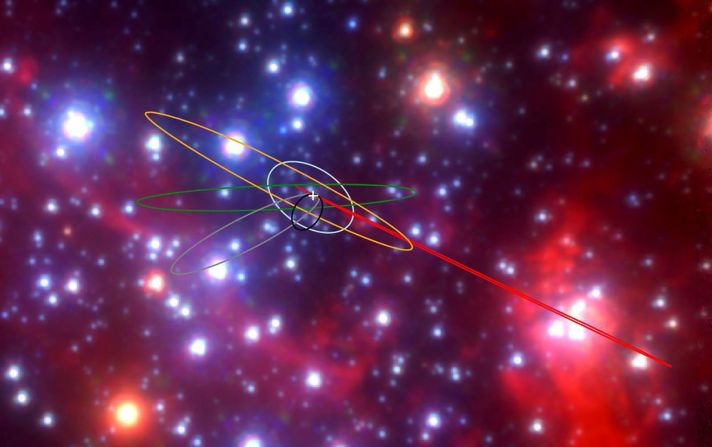

The researchers were also able to determine why this star is behaving in such a unique fashion. It’s one of two stars in a binary star system, partnered with a red dwarf star. Red dwarf stars are small, cool stars that are among the most common in our galaxy.

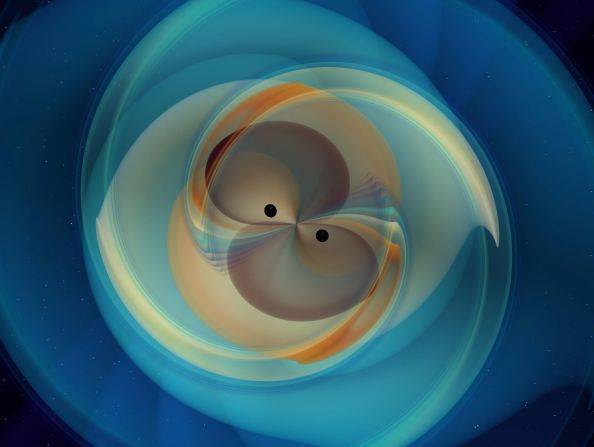

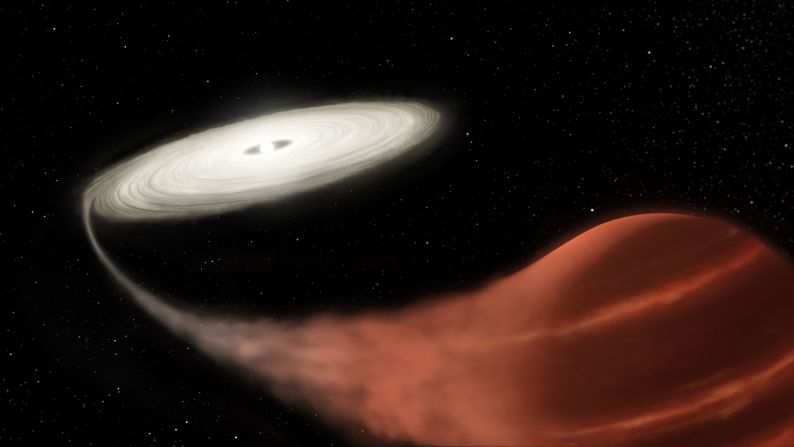

In this case, the two stars orbit each other so closely that they zip around each other in less than two Earth days. Given their proximity, the red dwarf star’s gravitational pull actually distorts the pulsations of the larger star. This causes the larger star to be distorted into more of a teardrop shape, rather than the usual sphere.

Amateur astronomers studying TESS data made available to the public spotted the star while searching for the telltale signals of planets around other stars. Many exoplanets, or planets found outside of our solar system, have been found to orbit red dwarf stars.

“The exquisite data from the TESS satellite meant that we could observe variations in brightness due to the gravitational distortion of the star as well as the pulsations,” said Gerald Handler, lead study author and professor at the Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Centre in Poland.

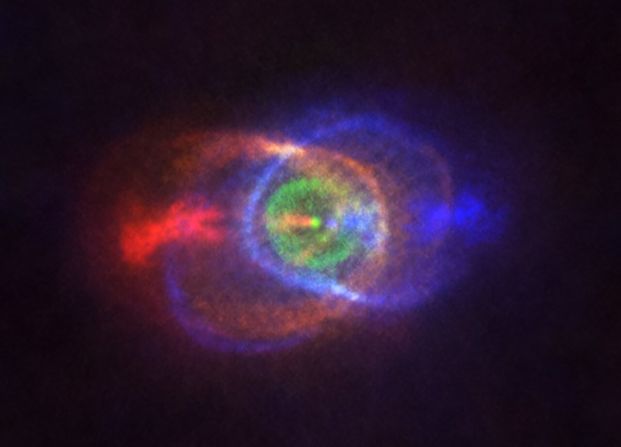

They were able to determine the source of the pulsation because the star varied in observations based on fluctuations in brightness, the angle of the star and how it was oriented in its binary system.

“As the binary stars orbit each other we see different parts of the pulsating star,” said David Jones, study co-author and researcher at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands. “Sometimes we see the side that points towards the companion star, and sometimes we see the outer face.”

The researchers said now that they’re aware this type of star exists, they expect to “find many more hidden in the TESS data.”