They are members of an unnecessarily large fraternity.

There’s Charles Johnson, the father of two whose wife died in Los Angeles during childbirth in 2016. He has turned his anger into advocacy.

And Darin Horath, who lost his fiancée and their newborn daughter in September in rural Indiana. For him, the emotions are still raw.

Justin Waclawek is among them. He lives in Buffalo, New York, with his 6-month-old daughter and has focused his energy on being a new father since losing his wife in August.

And there’s Craig Krejci in Ohio, whose first wife died in childbirth in 2012. He hopes that his journey can help other men for whom America’s maternal mortality crisis has hit home.

The rate of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States has steadily increased since 1987.

In 2018, the year with the most recent national data, 658 women in the United States died while pregnant, in childbirth or within 42 days after pregnancy, according to data in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistics Reports in January.

In 2017, the year with the most recent global data, the United States had a higher maternal death rate than the lower-income countries of Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Portugal, Qatar, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Uruguay, according to separate data from the World Health Organization and several other groups.

“Before this happened to us, I had no clue,” Charles said about the maternal mortality crisis and losing his wife Kira Johnson.

“I was oblivious to the fact that a woman that was in exceptional health, who was obsessive about her prenatal care, who did everything right, who was healthy and who was supposed to be at one of the best hospitals in the country would walk in and not walk out to raise her boys,” he said. “It just didn’t cross my mind.”

Charles, Darin, Justin and Craig are just some of the partners and fathers who have been left in the wake of America’s disturbingly high maternal death rate. They are outraged and heartbroken, but also hopeful and taking steps to heal.

Theirs is the other story of America’s maternal mortality crisis.

‘There is a failure and a disconnect’

Memories of Kira Johnson are prominent around the Atlanta home where Charles Johnson raises his two sons, 5-year-old Charles V and 3-year-old Langston.

Family photos hang on the walls and Charles said that he tells his sons to “make mommy proud” every day.

“For me, it’s a feeling of loss coupled with being lost – and understanding that there is no way that you can ever fill this void,” Johnson said about losing his wife. “I didn’t have the option of succumbing to my rage. I had to focus on what I knew Kira would want me to do and expect me to do, which was making sure that my boys were OK above all things.”

In April 2016, within 12 hours of welcoming his youngest son, Charles lost his wife Kira.

Langston was born via a planned Cesarean section at 2:33 p.m., and after Kira was out of the operating room, Charles said that he noticed blood running through her catheter – a sign of excessive bleeding or postpartum hemorrhage.

“I could see the Foley catheter coming from Kira’s bedside begin to turn pink with blood,” Charles said, adding that he told doctors numerous times about the bleeding and his concerns.

“It wasn’t until 12:30 a.m. the next morning that they finally made the decision to take Kira back to surgery,” he said. “When they took Kira back to surgery, and he opened her up, there were three and a half liters of blood in her abdomen, from where she had been allowed to bleed internally for almost 10 hours, and her heart stopped immediately.”

At 2:22 a.m., Kira was pronounced dead at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, according to a lawsuit that Charles filed. She was 39 years old.

Charles, the son of prominent TV judge Glenda Hatchett, sued the hospital in 2017 for the death of his wife. With the case still pending, Cedars-Sinai told CNN in a statement that the hospital could not respond directly due to privacy laws.

Overall, “Cedars-Sinai thoroughly investigates any situation where there are concerns about a patient’s medical care,” the hospital said.

Charles has been working as an advocate to raise awareness around maternal mortality – and especially how women of color in the United States face dramatically higher maternal death rates than white women. Kira, a black woman, was in that highest risk group.

Black and Native American women are about three times as likely to die from pregnancy or delivery complications as white women. That disparity increases with age, as black and Native American women older than 30 are four to five times as likely to die from complications, according to the CDC.

This disparity remains despite the mother’s socioeconomic status and education level. Kira was a successful entrepreneur who spoke five languages, ran marathons and had her pilot’s license.

“There is a failure and a disconnect for the people who are responsible for the lives of these precious women and babies to see them and value them in the same way that they would their daughters, their mothers, their sisters,” Charles said.

Charles now works to raise awareness around maternal death.

In 2017, he launched the organization 4Kira4Moms to advocate for improved maternal health policies in his late wife’s honor. His work included advocating for the passage of the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act.

Congress passed that legislation in 2018, which provides funding for state and local surveillance of maternal deaths. Some of that funding supports the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health or AIM, which provides approaches that states can take to improve maternal safety and outcomes, including specific tools and initiatives.

Johnson said that the work being done through the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act and AIM has been “tremendous,” but action is needed to make tools and protocols mandatory.

“When these tools and these protocols are suggestions and not mandate, that’s where the implicit bias and the arbitrary decision-making slips in,” he said. “So we’re looking for additional oversight. We’re looking for standards that are mandated and not just suggested for prenatal care. We’re looking at standards for transparency and very importantly accountability.”

While reflecting on Kira’s death, Charles said, “There’s nothing that can prepare you for what it’s like when your child wants to know why mommy isn’t coming home.”

He hopes that his advocacy can help “prevent one Dad from having to have these conversations with their children.”

For some, maternal mortality can include the devastating loss of a child too.

‘To be blunt, it’s a living hell’

Darin Horath is taking time to heal in New Mexico – some 1,200 miles from his home in Indiana. That’s where he lost his fiancée, Maryanne Holiday, and their daughter, Isabella, in childbirth in September.

“To be blunt, it’s a living hell,” Darin said.

The deaths came after Mary underwent an emergency C-section in late September. About 45 minutes after the procedure, Mary’s doctor told Darin and Mary’s mother that the baby had died. Mary was still in recovery at the time.

Mary’s doctor asked, “‘Which one of you two want to give her the news when she wakes up?’” Darin took a deep breath, looked at the doctor and said, “’If you go in there with me, I’ll tell her.’ And her doctor said, ‘Absolutely, no problem.’ “

What happened next, Darin said, was a blur.

Mary’s health took a turn and her medical team immediately made preparations to rush her to another hospital. Before they were able to move her, she died of an amniotic fluid embolism, Darin said. She was 31. Darin didn’t have a chance to tell her about Bella.

The condition, also called AFE, is a rare but catastrophic complication of pregnancy in which amniotic fluid or other debris enters the mother’s circulatory system.

The Amniotic Fluid Embolism Foundation notes that “AFE is a life-threatening, acute and unexpected birth complication that can affect both mother and baby” and “the exact mechanism of what causes AFE is unknown and it remains unpreventable.” The foundation also notes that amniotic fluid or fetal debris often enter the mother’s bloodstream during labor but only in some cases it can result in life-threatening illness or death.

“We didn’t know about the mortality rate, AFE, anything,” Darin said. “It was all new.”

As Darin takes the time to grieve, he cherishes the memories he shared with Mary. They met online – even though Darin programmed the settings in his online dating profile to connect him only with people within 50 miles.

“She was the only one that popped up out of 50 miles away,” Darin, 46, said.

“Things progressed and we started talking about starting our own little family. We found out she was pregnant, and we were going to get married before she had Bella but she decided to wait until afterwards because she wanted Bella in our wedding,” he said. “So that was our plan.”

Darin is grateful for his friends who are hosting him in New Mexico as he heals, he said. Next, he plans to return to the Midwest to be near family: his parents, brother, sister and 20-year-old son from a previous relationship.

He encourages other fathers in his same situation to “definitely see a therapist about it, friends and family – that’s basically how I’m getting through it.”

In the meantime, Darin said he hopes his story can shed light on a “very real problem” in the United States.

“It’s 2020 now,” he said. “Stuff like this shouldn’t happen.”

‘Everyone keeps asking me if I’m OK. I tell them I have to be’

Justin Waclawek and his wife Alison, both pharmacists, were aware of the maternal mortality crisis in the United States but never thought they would be personally impacted.

“I’ve known that the US has a higher rate than a lot of the other developed countries, which is shocking,” Justin said from his home in New York. “My wife had traveled to some third-world countries and had seen the birthing process over there and we had discussed when she got back how crazy it is that we still somehow have a high maternal death rate.”

Then in August, following a healthy pregnancy, Alison had complications after her labor was induced. She was rushed into an emergency C-section, where she died of an amniotic fluid embolism at age 31. Justin and Alison’s daughter, Ada, survived, but was monitored and intubated for one week.

“A week later, we had a memorial service for my wife and I got to take my baby home afterwards,” Justin said, choking up a little as he spoke.

Ada is now a healthy 6 month old. When she has difficulty sleeping through the night, Justin remains by her side. When she refuses to drink her bottle, he keeps his patience. Family and friends help him care for his newborn daughter by watching her whenever he needs to do laundry or simply take a shower.

“Everyone keeps asking me if I’m OK. I tell them I have to be,” Justin, 30, said matter-of-factly.

“I have this tiny little life that depends on me for everything,” he said. “It’s like riding a rollercoaster. You have these highs when she does something that makes you smile and then it just hits you that Ali’s not here to see it, too.”

Justin said he met Ali, a former cheerleader for the Buffalo Bills, in pharmacy school.

“The first time I saw her, it sounds so cliché, but my eyes just lit up. I mean, she was gorgeous,” he said. “She just really cared about her patients and her people and everyone in her life and she had that ability that when you looked at her, you believed what you were saying was important. She had a way of making everyone feel special.”

Now Justin notices that same quality in their daughter Ada.

“Her eyes do that same thing when she sees you or she sees someone,” he said. “They sparkle.”

Finding hope after loss

Craig Krejci, 43, has had nearly a decade of healing after the maternal death of his son’s mother – and he hopes that his journey can help other fathers and offer them hope.

Paula Mounts and Craig had one of those movie plot romances.

They worked together at Key Bank in Cleveland, Ohio, and crossed paths often. Almost everyone around them sensed sparks, but it took years for Paula and Craig to let those sparks fly.

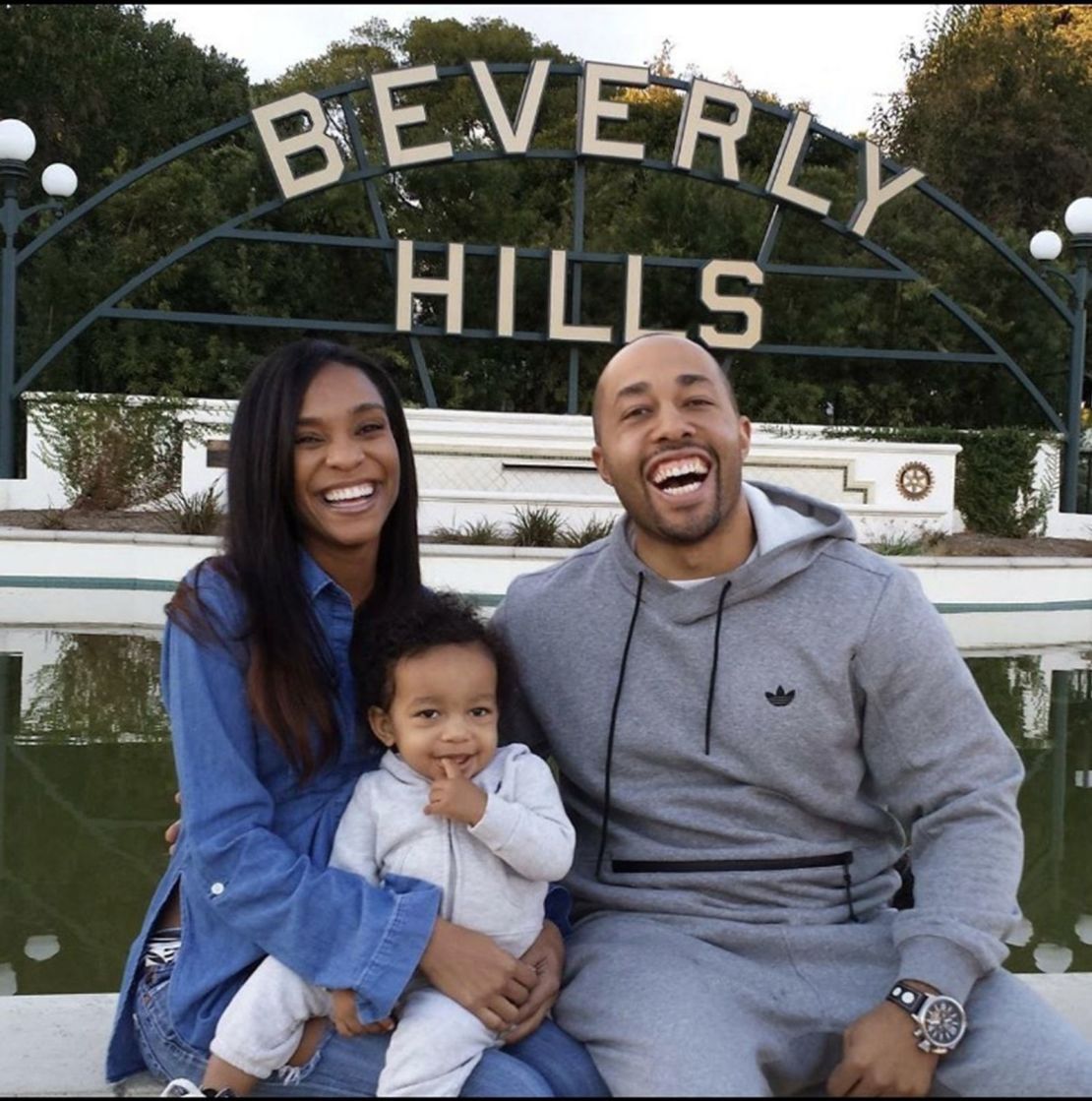

They started dating in 2010, wed a year later in Mexico and then became pregnant with their first child – a baby boy.

Paula, who was 36 at the time, immediately called her younger sister, Kristi Gray, to share the pregnancy news. The women, four years apart, were best friends. She could hear Paula’s joy through the phone.

“She was really excited – it was her first baby,” Kristi said.

In the months that followed, “we had a completely healthy and fine pregnancy the entire way,” Craig said.

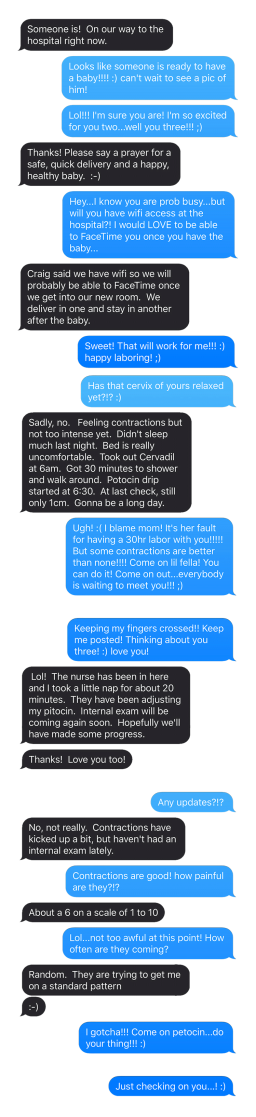

As time drew closer to Paula’s delivery date, she did not go into labor naturally – and at 41 weeks pregnant, which is considered a late-term pregnancy, Kristi said that Paula’s medical team decided to induce her labor.

While Paula was on her way to the hospital in Ohio, she texted to Kristi: “Please say a prayer for a safe, quick delivery and a happy, healthy baby. :-)”

Kristi, who was still in Atlanta, continued texting back and forth with Paula during the labor. The last text she sent to Paula was “Just checking on you…! :)”

On that Monday in late August 2012, Paula experienced complications and died of an amniotic fluid embolism. Paula and Craig’s baby, named Mason, survived the birth, but was monitored in the neonatal intensive care unit for six days.

“A lot of those days were obviously spent taking trips back and forth to the NICU,” Craig said.

“Mason did not come home until the following Sunday,” he said. “We had a lot of family and friends coming into town for the funeral. It was kind of a blur, assessing what happened, taking the next steps and the plans. … Obviously, I was still in shock.”

Once Mason was home, Craig said that his parents and Paula’s family helped him care for his newborn. While raising Mason, Craig has made an effort to be as transparent as possible with his son about what happened with Paula.

“We wanted him to understand,” Craig said. “We would show him pictures and explain she had to go to heaven and she still watches over you. We even found books around loss.”

From the time he was old enough, Kristi said that Mason has understood that “Paula is in heaven.”

“He would even go to my dad’s house and he would say, ‘Can I go speak to mommy Paula?’ And he would literally go down to where a picture of Paula was and he would just have a conversation with her,” Kristi said. “He’s done that multiple times – or when he was younger, he would look up at her picture and my dad would catch him just staring at her.”

As time went on and Mason grew older, Craig started to consider dating again. He first brought it up to his parents and Paula’s parents.

“The conversation about starting to date again I thought was going to be awkward, but everybody supported it completely, especially on Paula’s side,” Craig said.

When dating, he made an effort to be upfront and transparent about being a single father. Before long, he met his wife, Kate, and they instantly had a connection.

“Kate now is so engrained in the entire family – they text her and not me. They treat her like an equal and it has been a very smooth transition,” Craig said. “I got very lucky.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Paula’s family now hosts a 5K memorial fundraiser in memory of Paula each year to support the AFE Foundation, a patient advocacy organization that funds AFE research.

The event allows Craig, Kate, Mason, Kristi and other family members and friends to gather together. It was at that event in September when Mason, now 7, met Kristi’s infant son for the first time. The family was beaming with pride.

As Craig reflects on his life and family, he said that there is no blueprint for getting through grief – it will be a different journey for different people.

“I think every person’s situation is going to be different in how they handle the grief,” he said, “and how they want to plan out the rest of their life.”

CNN’s Robyn Curnow contributed to this report.