If America does not collectively adopt healthier eating habits, over half of the nation will be obese within 10 years.

Even worse, one in four Americans will be “severely obese” with a body mass index over 35, which means they will be more than 100 pounds overweight.

That alarming prediction, published Wednesday in NEJM, was the result of a study analyzing self-reported body mass index (BMI) data from over six million American adults.

Considering the challenges of battling weight loss, that’s devastating news for the future health of our nation.

“Given how notoriously difficult obesity is to treat once it’s established, you can see that we’re in an untenable situation,” said Aviva Must, chair of Tufts University’s Public Health and Community Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

“The societal cost is high,” she said, “both in terms of obesity-related health consequences and healthcare expenditures which could bring us to our knees.”

Startling state-by-state data

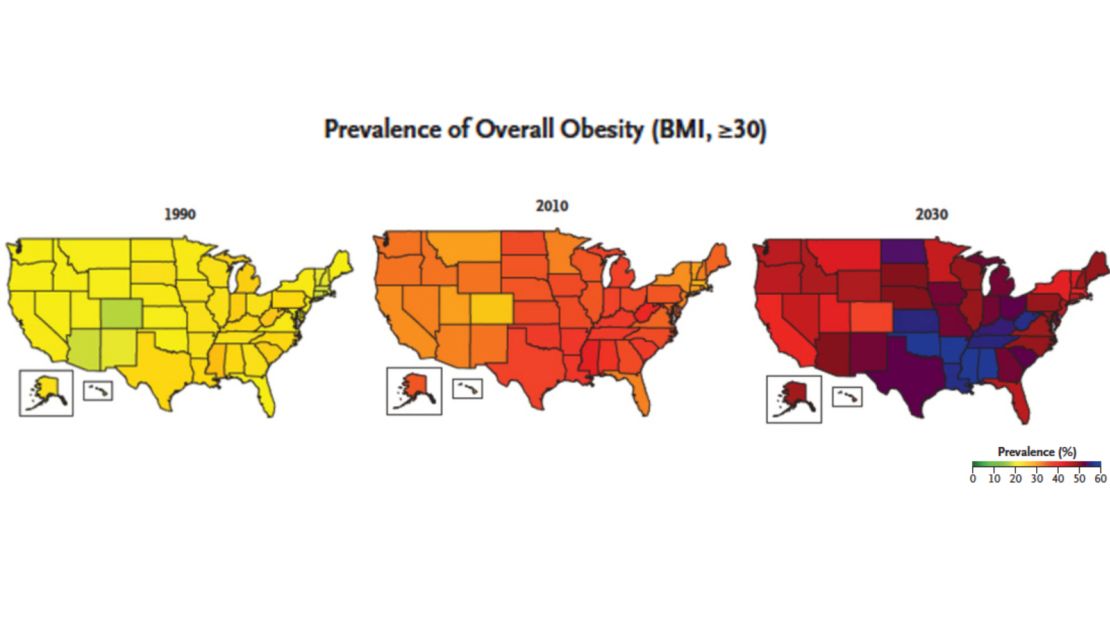

One of the first research efforts to drill down to the state level, the study found that 29 states, mostly in the South and Midwest, will be hit hardest, with more than 50% of their residents considered obese.

But no part of the country is spared – in all 50 states, at least 35% of the population will be obese, the study found.

“What’s even more concerning is the rise in severe obesity,” said lead author Zachary Ward, an analyst at Harvard Chan School’s Center for Health Decision Science.

“Nationally, severe obesity – typically over 100 pounds of excess weight – will become the most common BMI category,” Ward said. “Prevalence will be higher than 25% in 25 states.”

Currently, only 18% of all Americans are severely obese. If the trend continues, the study said, severe obesity would “become as prevalent as overall obesity was in the 1990s.”

The study also found certain subpopulations to be most at risk for severe obesity: women, non-Hispanic black adults and low-income adults who make less than $50,000 per year.

“And we find that for very low-income adults – adults with less than $20,000 annual household income – severe obesity will be the most common BMI category in 44 states,” Ward said. “So basically everywhere in the country.”

What happened?

“Fifty years ago, obesity was a relatively rare condition,” Must said. “People who were poor were underweight, not overweight. But that has changed.”

One reason is the rise of sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods, which contribute calories but little nutrition. Another is that the price of food, including unhealthy fast food choices, has fallen in America when you adjust for inflation.

“Low food prices are certainly part of it,” Must said. “Also limited options for physical activity. And there’s a lot being written about the stress of structural racism and how that influences people’s behavioral patterns. So it’s very complicated.”

Can we fix it?

“There’s no rosy picture here, but I don’t think we can throw in the towel,” Must said. “It will probably take lots of federal, state and local policy interventions and regulations to have a big impact. We can’t rely on individual behavior change in an environment that is so obesity promoting.”

Studies have shown some promising tactics, she said: bolstering local public transportation systems to encourage walking instead of driving; keeping schools open on weekends and during summers to allow access to gyms and swimming pools; and increasing support for farm-to-school and farm-to-work food programs, as well as farmers’ markets, to boost access to low-cost fruits and vegetables.

Other interventions include calorie labeling on restaurant and drive-thru menus and replacing vending machines with smart snacks in schools.

“We’ve also looked at eliminating the tax deduction businesses get for advertising unhealthy foods to children,” Ward said. “The money that they spend on advertising foods can basically be written off as a tax deduction.

“That could be one reason why we see such disparities by race, ethnicity or income,” Ward said, “because companies are directly targeting advertising at these groups.”

In a prior study, Ward and his team at Harvard found that three interventions saved more in health care costs than the price to implement them: elimination of the tax deduction on advertising; improving nutrition standards for school snacks; and imposing an excise tax on sugary beverages.

The most cost effective solution was the tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. The study found the tax saved $30 in health care costs for every dollar spent on the program.

“So much added sugar is delivered through sugar-sweetened beverages, and people do have other options for hydration,” Must said. “I think it’s an easy target.”

But not necessarily a popular one. Still, the complexity of the problem means that a solution will truly take a village, experts say, with every American doing their part.

“I don’t think it’s impossible,” Must said, pointing to a slowing of the obesity rate in children in America. That trend is the result of interventions in school lunches; snack programs; and a change in the nutritional allowances in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, which helps feed more than seven million pregnant and postpartum women and children until age five.

In 2009 the program decreased the intake of foods and beverages associated with excess weight gain. By simply cutting the juice allowance in half, reducing cheese, requiring whole grain products and requiring low-fat or skim milk, a study found the program reduced the obesity rate in children between two and four years of age and boosted the intake of fruits and vegetables.

That is certainly a model for future attempts among both children and adults, Ward said, adding that if Americans could just keep their current weight instead of gaining, the trends could be reversed.

“It’s really hard to lose weight,” Ward said. “It’s really hard to treat obesity. So prevention really has to be at the forefront of efforts to combat this growing epidemic.”

A previous version of this story misstated the study time period.