A staggering 600 million birds die every year in the United States after colliding with tall buildings. And Chicago, with its skyscrapers and location on a major migration path, is perhaps the biggest killer.

But for Dave Willard, a collections manager emeritus at the city’s Field Museum, the dead birds have been an unexpected scientific windfall. Each morning in the spring and fall, when birds make their epic journey between Canada and Latin America, he has headed out to pick up the dead animals from the street.

“I’ve just stopped for the season. The number of birds we get each day is highly variable depending on whether it’s a big day of migration. The maximum is 300 in a day,” he said.

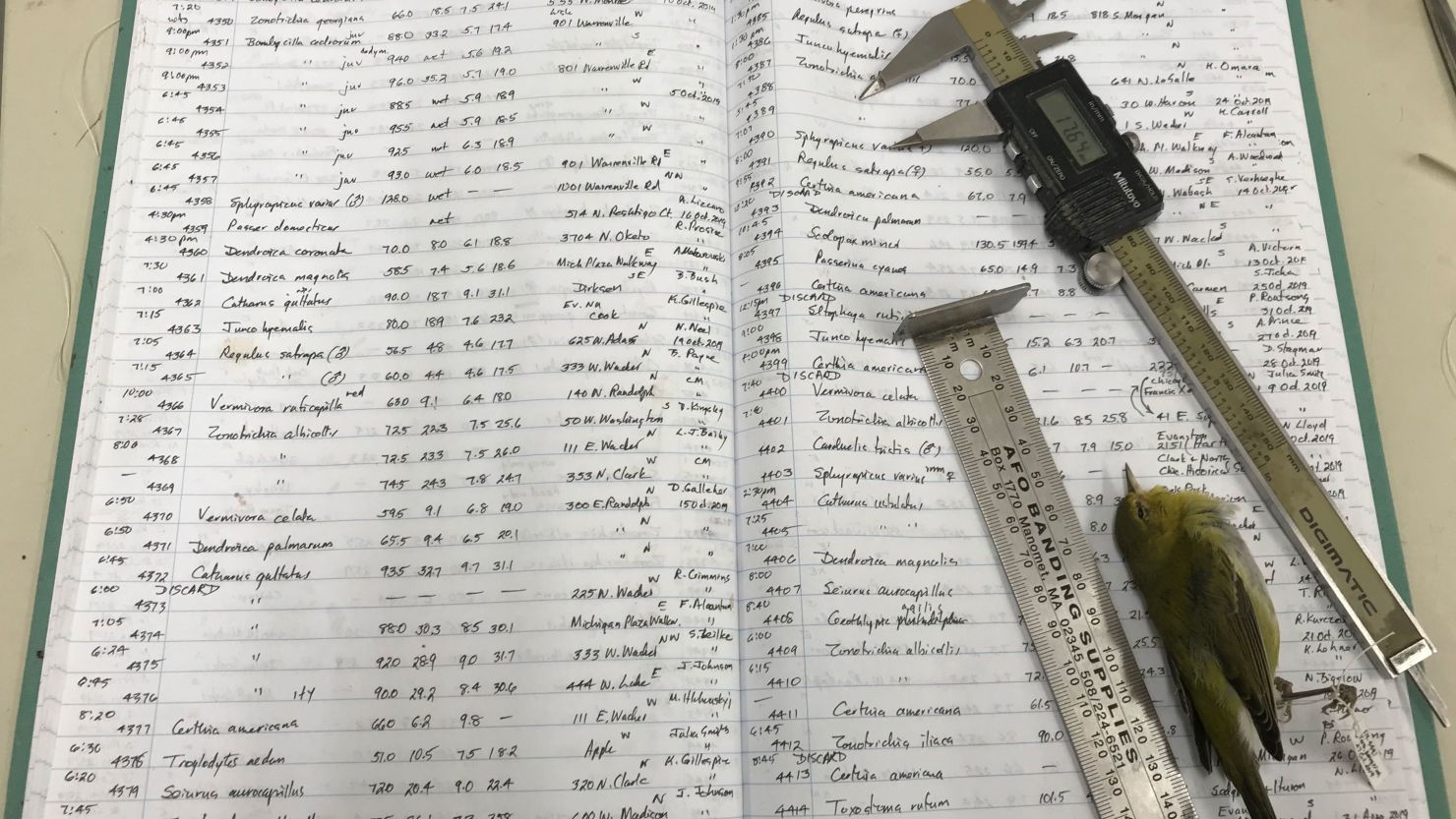

Along with a volunteer group, since 1978 he has collected more than 100,000 dead birds, carefully measuring them with a caliber and scale and cataloging the results by hand in a ledger.

Now, a comprehensive study of the unique and remarkably detailed data Willard amassed has shown that North American migratory bids have been getting smaller over the past four decades, and their wingspan wider. The changes appear to be a response to a warming climate.

“We had good reason to expect that increasing temperatures would lead to reductions in body size, based on previous studies,” said Brian Weeks, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability and lead author of the study that published Wednesday in the journal Ecology Letters.

“The thing that was shocking was how consistent it was. I was incredibly surprised that all of these species are responding in such similar ways,” he added in a press statement.

Warmer temperatures and smaller bodies

For the analysis, the biologists used 70,716 dead birds representing 52 species – including thrushes, sparrows and warblers – that Willard had logged between 1978 and 2016. Of those species, 49 saw statistically significant declines in body size. In particular, the length of the tarsus or lower leg bone, shrank by 2.4%.

Meanwhile, wing length showed a mean increase of 1.3%, with the species showing the fastest declines in tarsus length also showing the most rapid gains in wing length.

The authors suggested that the shrinking body sizes are a response to climate warming, with temperatures at the birds’ summer breeding grounds north of Chicago increasing roughly 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) over the course of the study.

Within animal species, individuals tend to be smaller in warmer parts of their range – a pattern known as Bergmann’s rule – the researchers said. Larger body sizes help animals in cold places stay warm, with smaller bodies holding on to less heat.

The bird’s wingspans may have increased to compensate for smaller bodies that produce less energy for the incredibly long distances the birds travel during their migrations.

While the changes in the birds’ body shape are subtle and not detectable by the human eye, the biologists said that the study is the largest of its kind and shows the most consistent large-scale responses for a diverse group of birds.

“Periods of rapid warming are followed really closely by periods of decline in body size, and vice versa,” Weeks said.

“Being able to show that kind of detail in a morphological study is unique to our paper, as far as I know, and it’s entirely due to the quality of the dataset that David Willard generated.”

The possibility of body size reduction in response to present-day global warming has been suggested for decades although evidence supporting the idea remains mixed.

Next, the researchers plan to use the data base to look at the mechanism behind the body size and shape changes and whether they are the result of a process called developmental plasticity – the ability of an animal to modify its development in response to a changing environment.

Willard began collecting the dead birds after someone casually mentioned they were hitting windows, including at McCormick Place, North America’s largest convention center, which is just a mile away from the Field Museum. Willard said he headed down there thinking, “Why let them go to waste when they could be specimens in a museum?”

“When we began collecting the data analyzed in this study, we were addressing a few simple questions about year-to-year and season-to-season variations in birds,” said Willard. “The phrase ‘climate change’ as a modern phenomenon was barely on the horizon.”