Editor’s Note: Robert Klitzman is a professor of psychiatry and director of the masters in bioethics program at Columbia University. He is author of “Designing Babies: How Technology is Changing the Ways We Create Children.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The Trump administration put into effect new regulations just weeks ago that impede a crucial area of biomedical research – one which has helped millions of Americans. These new requirements have gone largely unnoticed, given the shifting daily barrage of political news, but this change should not be slipped under the rug. While political chaos understandably has dominated recent news, we should not simply ignore other important issues that affect us all.

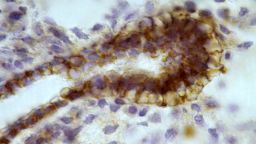

The use of a unique set of cells – human fetal tissue cells – has led to immense medical breakthroughs, including the development of vaccines for polio, measles and rubella, and improved understanding and treatment for Parkinson’s disease, cystic fibrosis, Ebola, HIV, Zika, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other disorders. These cells are taken from fetuses after elective abortions.

But President Donald Trump, to the delight of many anti-abortion groups, has thwarted any such future scientific advances by placing an additional layer of scrutiny on National Institutes of Health (NIH) research proposals that would use these cells. The new regulations, which went into effect on September 25, require, for example, that scientists seeking to discover treatments for specific diseases must now adequately justify, to a newly-formed “ethics advisory board,” each study’s scientific merit, and how they determined that no alternatives exist to using these cells.

This board could thus insist that scientists must first waste precious, limited time and resources trying a number of other possible scientific methods to demonstrate that they fail before using fetal tissue. Luckily, there is still time for Congress to step in and prevent the administration from stymying crucial scientific progress.

In announcing the new requirements, the Department of Health and Human Services states that “Promoting the dignity of human life from conception to natural death is one of the very top priorities of President Trump’s administration.” The phrase, “the dignity of human life from conception,” reveals the underlying anti-abortion bias. Embryos are worthy of respect, but many Americans support the right to have a legal abortion, and do not believe that life begins at conception.

These new restrictions parallel George W. Bush’s 2001 hindrance of stem cell research. In both instances, the scientific community has been overwhelmingly united in opposing these short-sighted, politically-motivated attacks on science that can aid millions of Americans.

Importantly, existing regulations already carefully review all fetal cell research, ensuring that it meets a high ethical standard. Women who wish to donate discarded fetal tissue already give careful informed consent. These new regulations merely add unnecessary bureaucratic burdens that will discourage vital research.

Some anti-abortion groups claim that other methods can be used instead, such as induced pluripotent stem cells or organoids – clumps of cells from only one type of precursor cell that form only one kind of tissue.

Yet these methods can produce certain insights, but not others. NIH hopes to fund up to $20 million on alternative approaches and has, for instance, sought comments on “potential alternatives” using mice, and other approaches. But these other techniques are in no way full alternatives or replacements for fetal tissue. Mice can shed light on certain biological processes but differ from humans in critical ways. Though promising in several areas, organoids and iPS cells involve cells created by scientists in small plastic lab containers, outside natural conditions and the body, completely isolated from any surrounding blood, nerve or other immune tissues needed for life itself.

Such products therefore have major limitations – too simple for examining the complex interactions between different types of cells that are critical in countless diseases and treatments. These other methods will unfortunately not be able to yield countless insights and benefits that fetal cells can provide. Fetal tissue is unique, able to advance new disease treatments in ways that these other cell types cannot.

The human immune system, for example, depends on white blood cells that destroy viruses and bacteria, but develop only in later fetal stages. To learn how to fight infection, these cells need to migrate and be educated by different fetal organs like spleen and thymus – which occurs in a fetus, but not in a dish. Scientists have tried but been so far unable to make these cells in isolation in a lab.

Fetal tissue is therefore uniquely useful for understanding and potentially developing vaccines and/or remedies for various infections and congenital abnormalities. Fetal cells are also important for comprehending neurological disorders, since we cannot remove tissue from live human brains for study to see what works over time. Thymus tissue discarded from surgeries performed on infants, which some anti-abortion groups allege could be used instead of fetal tissue, is in fact relatively rare – doctors perform many times more terminations of pregnancies than cardiac surgeries on infants, and in not all these surgeries on infants is the thymus removed. Some research also shows that removing the thymus can harm these infants as they get older. And even if surgeons remove this gland, not all parents would agree to have it used for research. There is not enough thymus tissue to advance science in the ways that fetal cells can.

Proponents of these regulations might argue that funding from individual states and private sources would be adequate for projects involving fetal tissue. But these studies often constitute early basic research, essential for developing treatments for myriad diseases. And NIH funds the majority of such basic biomedical work – on which the pharmaceutical and biotech industries depend to then test and market medical interventions.

If we don’t pursue this fetal tissue research, other countries, such as China, surely will, and then they will own the intellectual property and patents that emerge, gaining the economic benefits of these discoveries, along with the attendant scientific prestige.

The House of Representatives has taken an important step by voting to block part of Trump’s new regulations with an amendment to prevent an ethics board from reviewing NIH grant applications for research studies. But the Senate has not yet considered this possibility, and many scientists fear staunch Republican opposition.

The House and Senate should work together, through the appropriations process that is expected to continue until December 20, to overturn or at least temper these new restrictions. After all, the countless disorders fetal tissue research can impact all cross the political aisle.

If Congress does not halt these regulations, it should mandate that this new ethics committee is in fact balanced and recognizes the enormous value of the investigations at stake. Congress should also stipulate the criteria this board will use to evaluate each research project, and mandate that the committee should not evaluate the ethics itself but will merely verify that the existing robust ethical reviews have occurred through current research ethics committees, known as Institutional Review Boards or IRBs. Otherwise, this committee could argue that fetal tissue use is never morally justified.

Science has extended and improved human lives and can continue to do so. To be sure, we must proceed with care, following ethical principles to decrease risks and maximizing potential benefits of research, but that does not mean stopping such advances altogether. Instead, policy makers, patient advocacy groups and others should work together to aid, rather than block research that promises to yield treatments to assist all Americans.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the process through which Congress could overturn or temper the fetal tissue cell regulations. It is the appropriations process.