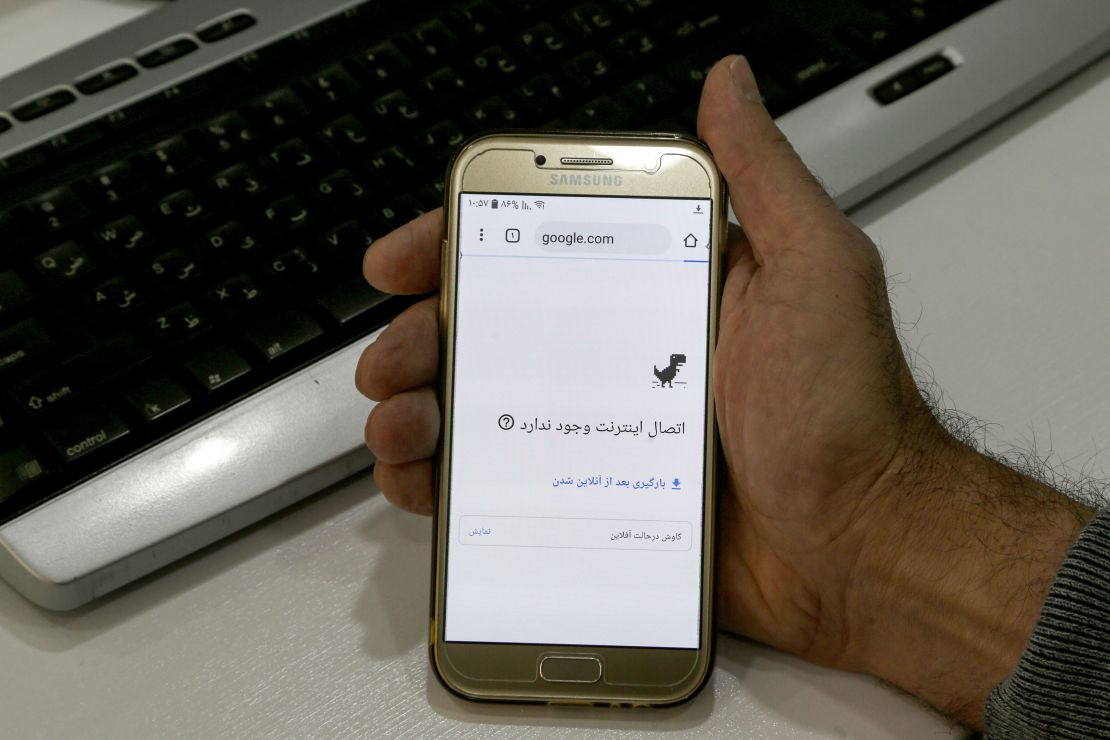

Iranians are still offline, three days after the government pulled the plug on the internet amid nationwide anti-government protests.

Experts say the shutdown is an attempt by the government to stop the flow of information and quash the demonstrations. David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, told CNN that the blackout makes it “harder for people to organize, harder for people to protest.”

“The impact is extraordinarily disproportionate because (it makes) it almost impossible for people to communicate with one another on the ground (and) with friends and family overseas and impossible for people to get information,” Kaye said.

Iran’s minister of telecommunications Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi said that the government had ordered the cutoff on Saturday and promised that it would return “soon,” state broadcaster Press TV reported Monday.

“Internet will return to the life of the Iranian people soon and the government [will] continue to develop it,” Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi said, according to Press TV. He added that some essential online services had been switched to Iran’s National Information Network (NIN), a centralized national intranet.

But on Tuesday, connectivity in Iran was down to just 4% of normal levels, according to Netblocks, a non-governmental organization that monitors internet governance.

“Despite authorities’ attempts to make some internal services available to a limited number of users, the shutdown continues and the internet as we know it is not available in Iran,” NetBlocks’ executive director Alp Toker told CNN.

Most complex shutdown yet

This is not the first time that Tehran has shuttered online access to stop information from spreading. “After the 2009 presidential election, the Iranian government realized that the internet is key for communication between people not just inside the country, but also outside the country,” Amir Rashidi, an internet security and digital rights researcher at the Center for Human Rights in Iran, told CNN. The center is a civil society non-profit organization based in New York.

“When the mass protests were going on in Iran in December 2017 and January 2018, as soon as they shut down Telegram, basically the protest was finished because people were not connected to each other and they couldn’t communicate,” he added.

This time though, the shutdown appears different.

Toker described the blackout as the “most severe disconnection tracked by NetBlocks in any country in terms of its technical complexity and breadth.” According to NetBlocks’ data, the switch off itself was so complex that it took 24 hours to complete.

And Doug Madory, the director of internet analysis at Oracle, said the latest incident is unusual in its scale. In the past, he said, Iran would either intentionally slow down the internet through bandwidth throttling, or block individual websites such as Facebook and Twitter.

This current blackout is way more advanced. “We’re seeing a variety of different actions take place – some networks have withdrawn their routes while others continue to announce routes but block traffic,” Madory wrote in a blog on Oracle’s website.

Kaye added that while Iran has been blocking websites for many years, it has not previously cracked down on the use of VPNs, private networks that allow users to bypass bans. He said the move suggests that “the concern isn’t merely that Iranians might communicate with one another, but also that they might communicate with the outside world and tell people what’s happening.”

Madory added that while the internet has grown bigger and more complex in Iran in recent years, the basic structur remains the same: Connectivity between Iran and the rest of the world flows only through state-controlled entities, which serve as “bottlenecks between Iran and the global internet.”

“These chokepoints suggest the Iranian government has architected, and will likely retain, the ability to control (and in recent days block) internet access of its people,” he said.

‘Shutdown epidemic’

The drastic measure taken by Iran is not unique. Myanmar, China, India, Zimbabwe, Venezuela and other nations have also previously blocked the internet.

“There’s a kind of epidemic of internet shutdowns around the world. And they all seem to have the same kind of impact and motivation,” Kaye said. “It’s a real effort to deprive people of their basic human rights to access information worldwide.”

Apart from blocking people from talking to each other, the blackouts are also radically limiting the amount of information that gets out of the country.

That has been the case in Indian-controlled Kashmir, where authorities imposed an almost complete communications blackout in August.

“We don’t know what’s happening in the country except through kind of intermittent information that might get out of the country,” Kaye said. “The design is clearly to make it harder for people to tell their story outside of the country.”