Editor’s Note: Julia A. Minson is an associate professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, where Charles A. Dorison is a doctoral candidate and Todd Rogers is a professor of public policy. The views expressed in this commentary are their own. View more opinion on CNN.

What were you doing on January 20, 2017?

Like many Americans, you may have tuned in to watch President Donald Trump give his inaugural address. Or, maybe like others, you may have avoided it entirely, for fear of how it would make you feel.

As behavioral scientists aiming to understand what drives political division, we saw this as a perfect opportunity to conduct an experiment. Seconds after the address ended, we used an online platform to recruit over 200 Americans who had voted for Hillary Clinton to participate in a survey.

We first asked the voters to predict how they expected to feel if they were to watch the 17-minute inauguration address (which most of them had avoided doing), by checking off which emotions they would experience and how strongly. We then asked them to watch the entire address and report how they actually felt by considering the same emotions again.

A few hours and a collection of angry emails later, we had our results: It turns out, listening to Trump’s inaugural address wasn’t as bad an experience for them as the Clinton voters had predicted. While our participants may not have been persuaded by many of Trump’s arguments, they ended up agreeing with more of his speech than they expected going in. Indeed, participants reported that the experience was better than expected 61% of the time, exactly as expected 11% of the time and worse than expected just 28% of the time.

To us, this study suggested that political disagreement might not elicit as much negative emotion as people typically expect it to. It also provided a small window into how Americans could begin to bridge divides by exposing themselves to contrary political positions.

Of course, one study was not enough to fully convince us. Maybe it was just something about this speech, or this day? Isn’t it the case that any president has a team of professional writers crafting speeches that would have broad appeal?

To test this possibility, in a new study we collected 15 arguments from Trump supporters and showed them to 400 liberal participants. Again, we found the same pattern: While the liberal participants didn’t find the experience overall pleasant, it wasn’t as negative as they expected going in. The majority of participants experienced stronger positive emotions and weaker negative ones than they expected.

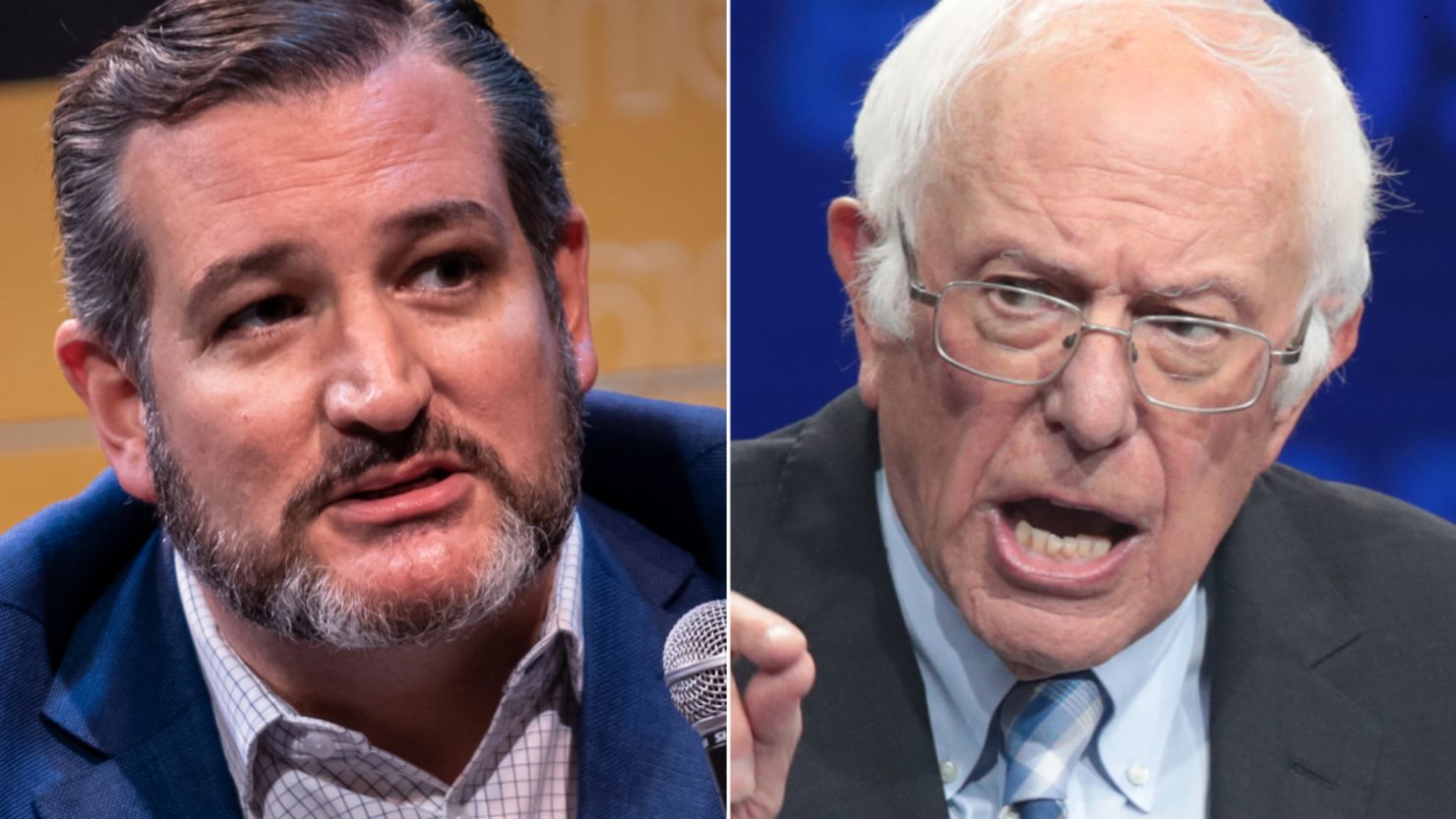

Still skeptical of our own results, we then conducted a follow-up study in which 200 liberals and 200 conservatives watched speeches by opposing-party senators (Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders). Here as well, listening to the other side turned out to be more tolerable than the partisans expected.

Importantly, the result was true for both sides – liberals (watching Cruz) and conservatives (watching Sanders). A couple more variations later – with a new set of speeches and a few new batches of participants – we were convinced.

The question was – why was this happening?

Individuals tend to avoid information that contradicts their prior beliefs. This phenomenon, called selective exposure, plainly means that people choose to only expose themselves to content they expect to agree with. Think of your conservative uncle who only watches Fox News, or your liberal nephew who listens exclusively to NPR.

In a recent study, conducted by researchers Jeremy Frimer, Linda Skitka and Matt Motyl, about two thirds of individuals preferred earning less money for study participation if it meant avoiding reading arguments opposing their beliefs. This, of course, can lead to concern that people form echo chambers, wherein like-minded citizens simply reiterate familiar and attractive positions.

Our paper, recently published in the journal Cognition, suggests that such selective exposure partly relies on miscalibrated emotional predictions.

People misjudge their emotions because they don’t realize that they will actually agree with some of the ideas on the other side. Even in the Trump inauguration speech, Clinton voters found some content they agreed with. When individuals overestimate how painful listening to the other side will be, they tend to avoid this information more than they otherwise would if they were making accurate predictions.

In fact, we find that simply teaching people about our research and thus recalibrating their emotional forecasts reduced selective exposure by up to a third. Liberal participants were more willing to listen to a speech by Cruz, and conservative participants were more willing to watch a speech by Sanders. And everyone was more willing to click on an opposing-party senator’s website and learn more about his or her policy positions.

Exposing ourselves to opposing views is no panacea. One rigorous experiment on Twitter demonstrated that encountering opposing opinions on social media may make things worse rather than better. However, our democracy requires us at a minimum to expose ourselves to a diversity of ideas.

Doing so is a necessary, but not sufficient, precondition for effective civil discourse. In today’s political environment, this can feel like a daunting task. But our research suggests a more hopeful outlook.

Whether you’re on the right or left, next time you encounter a headline from the other side, take the risk. It likely won’t be as bad as you think.