In this sport, a tiny miscalculation can mean the difference between victory and catastrophe.

And as difficulty levels soar to new heights, so do the risks of serious injury.

When Melanie Coleman, a gymnast at Southern Connecticut State University, died after falling off the uneven bars, veterans of the sport were stunned.

“It’s just not something that anybody can process,” her longtime personal coach Thomas Alberti said.

While a death in gymnastics is extremely rare, it’s happened before.

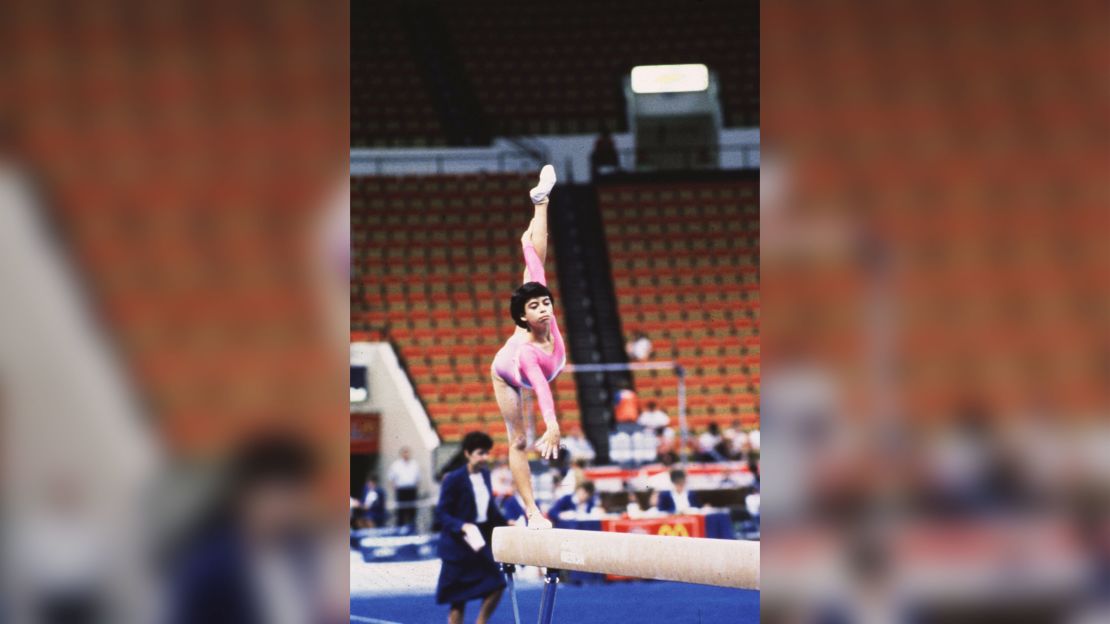

An Olympic hopeful’s tragedy helps change the sport

At 15, Julissa Gomez was on track to pursue her dream of competing in the Olympics. But just months before the 1988 Seoul Olympics, she slipped on a springboard that was supposed to propel her over the vaulting horse – the table that vaulters bounce their hands off of before flipping in the air.

Julissa’s head smashed into the horse, paralyzing her from the neck down. Three years later, the 18-year-old died of complications stemming from her injury.

After Julissa’s crash, the International Gymnastics Federation started allowing U-shaped mats around the vaulting springboard, wrote Joan Ryan, author of the book “Little Girls in Pretty Boxes.”

Yet more gymnasts suffered catastrophic injuries on the vault, leading to paralysis.

In 1989, Puerto Rican gymnast Adriana Duffy was paralyzed from the waist down after she crashed onto her neck.

In 1998, Chinese gymnast Sang Lan suffered a similar fate on the vault.

Widespread concern about these vaulting disasters helped lead to a major change in the future of gymnasts’ safety.

The thin vaulting horse that was easy for gymnasts to miss mid-air was replaced with a much broader vaulting table, giving gymnasts more room for error if their hands miss the mark.

When gymnastics gets too dangerous

Of course, catastrophic injuries such as paralysis are rare. But many gymnasts suffer a wide array of injuries as they test the limits of gravity and physics.

About 100,000 gymnasts suffer injuries every year, according to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Common injuries include wrist fractures, cartilage damage and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears.

And over the past 20 years, gymnasts have started the sport at earlier ages and are now performing more difficult skills, UPMC said.

In some cases, the skills are getting so dangerous that they’re actually banned.

The Thomas salto – first performed by American Kurt Thomas – involved leaping into the air and performing 1 1/2 flips and 1 1/2 twists. But instead of landing on their feet, gymnasts landed upside down, rolling forward on the backs of their shoulders.

In 1980, Soviet gymnast Elena Mukhina was attempting a Thomas salto when she broke her neck and became paralyzed. The move has since been banned for both men and women in international competition.

More recently, the debate over dangerous skills emerged this year when Olympic champion Simone Biles introduced a double-double dismount off the balance beam.

A double-double means a double backflip with two twists. Many gymnasts can’t do that on the floor, much less off a 4-inch-wide balance beam.

While gymnastics fans cheered the historic feat, officials came under fire for allegedly scoring Biles’ degree of difficulty too low.

Biles vented her frustration in a colorful tweet.

But the International Gymnastics Federation defended the scoring of Biles’ astonishing dismount, citing safety reasons.

“In assigning values to the new elements, the (Women’s Technical Committee) takes into consideration many different aspects; the risk, the safety of the gymnasts and the technical direction of the discipline,” the governing body wrote.

So while gymnasts push the sport to new heights, officials are pushing back. And that fine line between revolutionary and dangerous remains up in the air.