Americans spent $1.4 billion on the most popular brands of children’s fruit drinks and flavored waters last year. Yet according to nutritional guidelines, none of the drinks were healthy.

Why would loving parents do this? Perhaps because US beverage companies spent $20.7 million to advertise fun, fruity drinks with added sugars to families in 2018, according to Children’s Drink Facts 2019, a new report from the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity.

“I know that parents want their children to be healthy, but the sweetened drink market is just incredibly confusing to parents,” said lead author Jennifer Harris, the principal investigator for the three-year study funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics is alarmed that children consume so much added sugar,” said Dr. Natalie Muth, a pediatrician and lead author of the AAP policy statement on ways to reduce sugary drink consumption in children and teens.

“Added sugars increase the risk of many health harms including type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, heart disease and childhood obesity,” said Muth, who was not involved in the study. “Labels on drinks are confusing and misleading, causing parents to think they are providing their children a healthy drink when in actuality they are not.”

Confusing marketing

Two-thirds of the 34 sweetened drinks analyzed in the Children’s Drink Fact report contained no juice, yet images of fruit appeared on 85% of the packages. Most drinks which did contain juice capped the amount at 5%.

“Most of the sweetened drinks say, ‘good source of vitamin C’ or ’100% vitamin C’ but they have no or little juice,” Harris said. “A lot of them say ‘low sugar,’ ‘less sugar.’ But they don’t say it’s because there’s added low-calorie artificial sweeteners in there. It’s just very confusing.”

It’s not just parents. Children are being exposed to advertising, the report found. Kids between the ages of 2 and 11 saw twice as many ads for sweetened drinks than ads for beverages without added sugars, and four times as many ads as adults.

Two of the most popular drinks — Kool Aid Jammers and Capri Sun Roarin’ — advertised their drinks directly to kids on children’s TV programs, the report said.

Both drinks contain 0% juice but have pictures of fruit on the front of the packaging. CNN reached out to Kraft Heinz, who manufactures both products, and did not receive a response.

Many major drink manufacturers have pledged to change how they advertise to children.

The American Beverage Association (ABA), which represents some of the drink manufacturers, provided this statement: “Our companies strictly follow guidelines established by independent monitors that limit the marketing of beverages to children to 100% juice, water or dairy-based beverages and monitor TV, radio and digital advertising to confirm compliance.”

There are several loopholes in their responsible marketing policy, Harris said. For example, children do see ads when watching TV with their parents.

“Also, the ABA does not consider packaging designed to appeal to children as marketing to children,” Harris said. “Both Hi C and Tum E Yummies are Coca-Cola children’s sweetened fruit drinks with packaging clearly aimed at children.”

Added sugars and artificial sweeteners

One third of all the sweetened fruit drinks contained at least 16 grams of sugar, more than half of the maximum amount of sugar a child is supposed to get each day. A few are even worse, like Coca-Cola’s Minute Maid Lemonade fruit drink.

“The small 6-ounce juice box has 21 grams of sugar,” Harris said. “Children are not supposed to consume more than 25 grams of sugar a day. So that one juice box would use up most of that allowance for the day.”

When contacted by CNN for comment, Coca-Cola provided a link to recent efforts to reduce sugar across their portfolio.

Research shows that parents don’t want to give their child drinks with artificial sweeteners. Yet 74% of the tested sweetened fruit drinks and flavored waters contained low-calorie sweeteners. Both sugar and artificial sweeteners were in 38% of the beverages.

“If you look at the packaging of the products, it’s impossible to tell what’s inside the product just from the front of the package,” Harris said. “You have to turn it over and look at the ingredient list to see how much juice is in it, or to see if it has added sugar or low-calorie sweeteners.”

Starting on January 1, major brands with $10 million or more in sales must now disclose added sugars on the nutrition label on the back of all products, according ot new guidelines from the Food and Drug Administration. Smaller manufacturers have an extra year to comply.

But the new label will not list low-calorie artificial sweetener, Harris said. Those will remain hidden in the list of ingredients, requiring sharp-eyed parents to search them out.

One worry, she said, is that parents may not recognize the chemical names for sweeteners, such as aspartame, acesulfame-potassium, sucralose, stevia, neotame or saccharin.

Yet avoiding sweetened beverages, especially those that are extra sweet because they are artificially sweetened, is critically important for children under age 5.

“That’s the age when kids’ taste preferences are developing,” Harris said. “So, if they get used to really sweet products, and artificial sweeteners can be overly sweet, then when you try to get your child to drink plain water or plain milk, it just doesn’t taste good to them. Under 5 is a really critical time.”

Stevia, made from a plant leaf, is often considered by parents to be “healthy,” but Harris said there’s no evidence that “it’s any different from the other sweeteners except that it’s made from a leaf as opposed to chemicals.”

“Nobody knows the impact it may have,” Harris said. “Nobody has been able to do the research, especially with children.”

Reaction to the report was negative from health groups

Reaction to the Children’s Drink Fact report from national health and nutrition organizations was cutting.

“As a nation we have to say ‘no’ to the onslaught of marketing of sugary drinks to our children,” said registered dietitian Rachel Johnson, former chairwoman of the American Heart Association’s nutrition committee, in a statement.

“We know what works to protect kids’ health and it’s time we put effective policies in place that bring down rates of sugary drink consumption just like we’ve done with tobacco,” Johnson added.

The report recommends manufacturers clearly label all added sugars, including low-calorie sweeteners, and display the percentage of juice on the front of the drink package, where it is more likely to be seen by consumers.

The report also suggests that the FDA prohibit the misleading use of fruit images on drinks with little to no juice and require manufacturers to meet the nutritional claims on their packaging.

Finally, the report says state and local taxes on sugary drinks should widen to include children’s fruit beverages and flavored waters, with the hopes that higher prices would discourage use.

“This may include sugary drink taxes combined with increase education on health harms, such as through warning labels,” said the AAP’s Muth. “Parents also play an important role by modeling healthy drink choices and refusing to purchase sugary drinks.”

Healthier choices

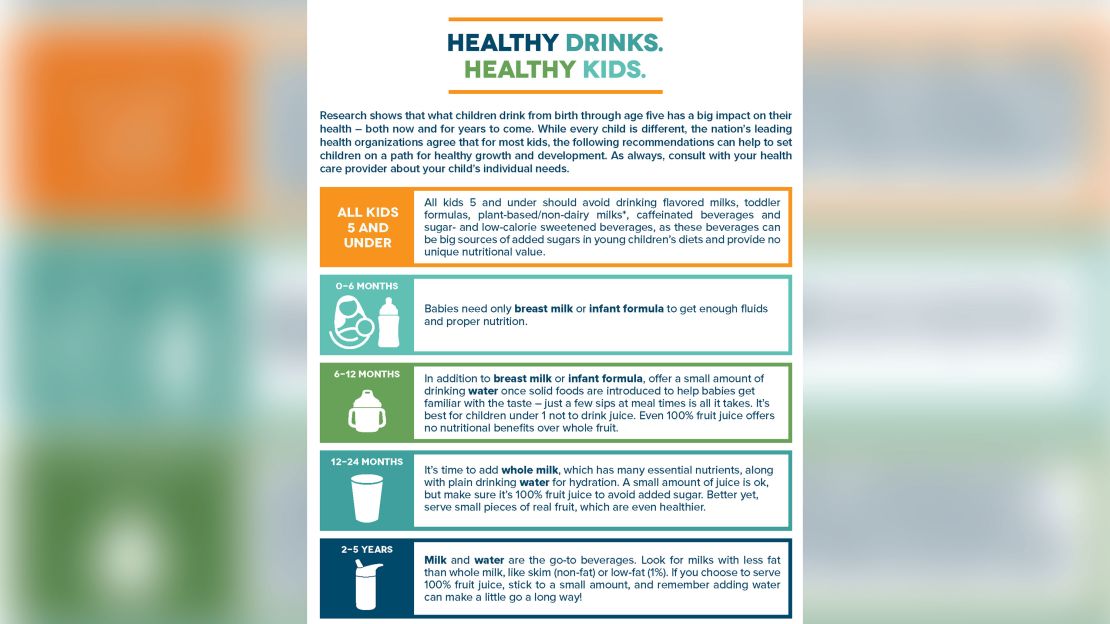

The American Heart Association joined the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry to publish a consensus statement in September that lays out what children 5 and under should drink.

“All kids 5 and under should avoid drinking flavored milks, toddler formulas, plant-based/non-dairy milks, caffeinated beverages and sugar- and low-calorie sweetened beverages,” the recommendations say, “as these beverages can be big sources of added sugars in young children’s diets and provide no unique nutritional value.”

Babies under six months only need breast milk and formula. As for juice, the group says it’s best to avoid juice for children under 1. “Even 100% fruit juice offers no nutritional benefits over whole fruit.”

That’s because the natural sugars in juice contribute to weight gain and dental decay as much as other sugars, say pediatricians. While juice does contain some vitamins and a bit of calcium, the overall lack of protein and fiber make it a poor choice for a healthy drink.

The drinks of choice for a child’s second year of life should be water and whole milk, the groups advises. “A small amount of juice is OK,” the recommendations say, “but make sure it’s 100% fruit juice to avoid added sugar. Better yet, serve small pieces of real fruit, which are even healthier.”

Between age 2 and 5 parents should move to skim or low-fat milk and keep pushing water to hydrate their children. Juice should be kept to a minimum and “remember adding water can make a little go a long way,” the guidance says.

And as the child grows, “water and milk are the preferred go-to beverages for all kids,” said Muth.

For parents who plan to provide 100% juice, the Children’s Drink Fact report had a bit of good news.

Beverage manufacturers have made some strides: there were 33 different brands of either 100% juice or juice-water blends.

But be careful with 100% juice boxes and pouches, the report said, because most contained more than 4 oz, which is the maximum daily amount of juice recommended for toddlers between the ages of 1 and 3. A few even contained more than 6 oz., the max recommended for preschoolers aged 4 to 6.

Most of the juice-water blends, the report said, contained less than 50 calories, and were lower in total sugars and calories than 100% juice.