Editor’s Note: Swanee Hunt, former US ambassador to Austria, is founder of the Women and Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and founder of Seismic Shift, an initiative dedicated to increasing the number of women in high political office. She is also the author of “Rwandan Women Rising.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

One of the most telling moments in the history of feminism occurred in 1838, at the Second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, an integrated meeting. The convention grew out of the correspondence of Maria Weston Chapman, a Boston abolitionist, and Mary Grew of Philadelphia, who had organized a school for black children, and their effort to coordinate the work of female anti-slavery societies.

Inside Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia, which had been built under abolitionist auspices and been dedicated only days earlier, 3,000 black and white women met to hear prominent abolitionists like the Grimke sisters, Lucretia Mott and William Lloyd Garrison speak. As men and boys hurled rocks through the windows, the speeches continued, even as they were drowned out by the pack gathered outside, outraged by the racially mixed gathering. The organizers had refused to submit to the mayor’s request that the meeting be restricted to white women only. The next day, a mob estimated at 10,000 burned down the hall – as police and firemen stood by. White and black women delegates linked arms to move through the crowd, and Sarah Pugh, a Philadelphia teacher who was president of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, offered the use of her school room as a place for the convention’s closing session.

One delegate to the convention, Laura Lovell of Massachusetts, recorded her impressions of the scene of the fire: “We walked out to witness the speedy destruction of that beautiful building which the diligent axe and hammer had been, for months, patiently rearing; that building, which the friends not only of abolition, but the friends of free discussion, the friends of civil and religious liberty, the true philanthropists and patriots of our land had reared….”

The report of civil authorities investigating the arsonists questioned how else residents could respond when confronted with “the unusual union of black and white walking arm and arm in social intercourse.” Unsurprisingly, a grand jury exonerated the rioters.

This episode captures in sharp relief how suffrage activism for women arose in the 19th century alongside anti-slavery passion, producing in special cases like the Philadelphia meeting, cross-racial affiliations. But risky collaborations like theirs were the exception; whether conscious or not – a sign of the times or not – racism was part of the women’s suffrage initiative from its earliest stages.

These were hardly cowardly women; were they being biased or strategic? The answer is: both. From the beginning, movements for civil rights for black Americans and for women have worked in both tension and synergy – and some of that persists to this day. So it’s important to look at the history to understand how we got here.

Far from being antiquated, this question about inclusiveness in the battle for the franchise now drives our work toward personal integrity, a sounder society, and a livable future. This week begins the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution, encoding the universal right of women to vote. We’d better get the next 100 years right.

Foremothers of women’s suffrage

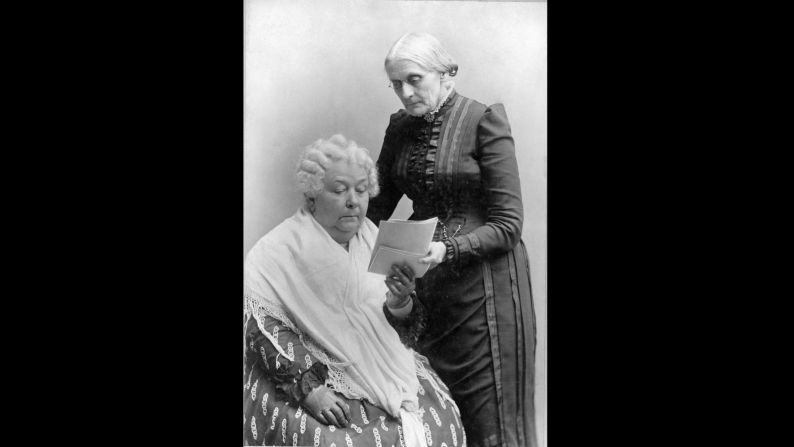

In 1848, over tea, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and four other women conceived a women’s rights meeting at Seneca Falls, New York. Five days later, eleven resolutions in the resulting Declaration of Sentiments were accepted unanimously. Only women’s suffrage passed with a razor thin margin. Some 300 people had unwittingly launched a world-changing crusade.

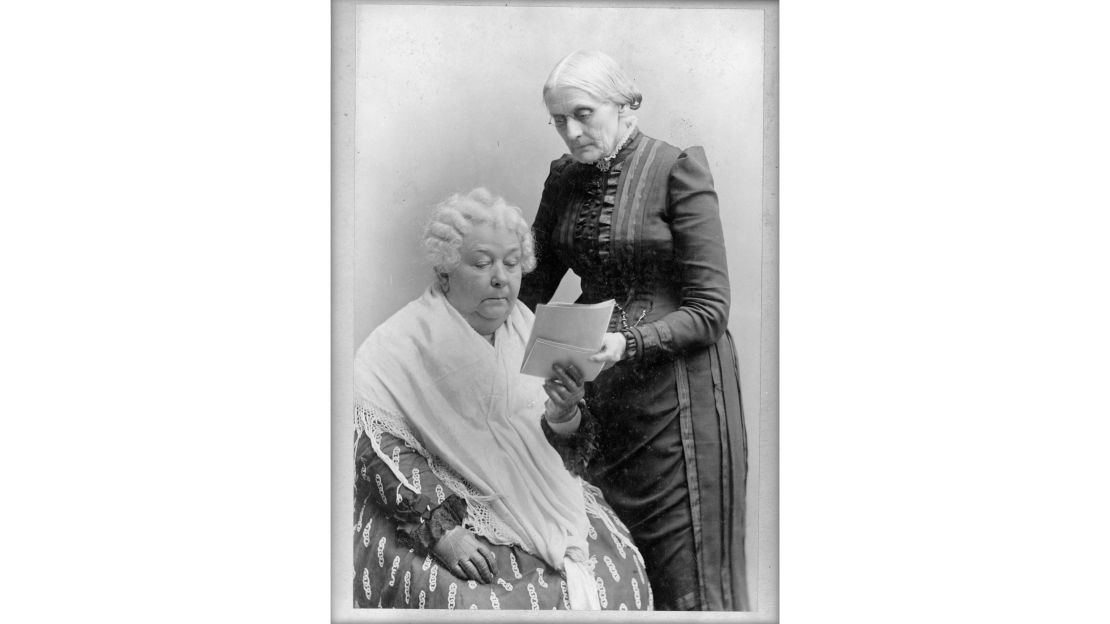

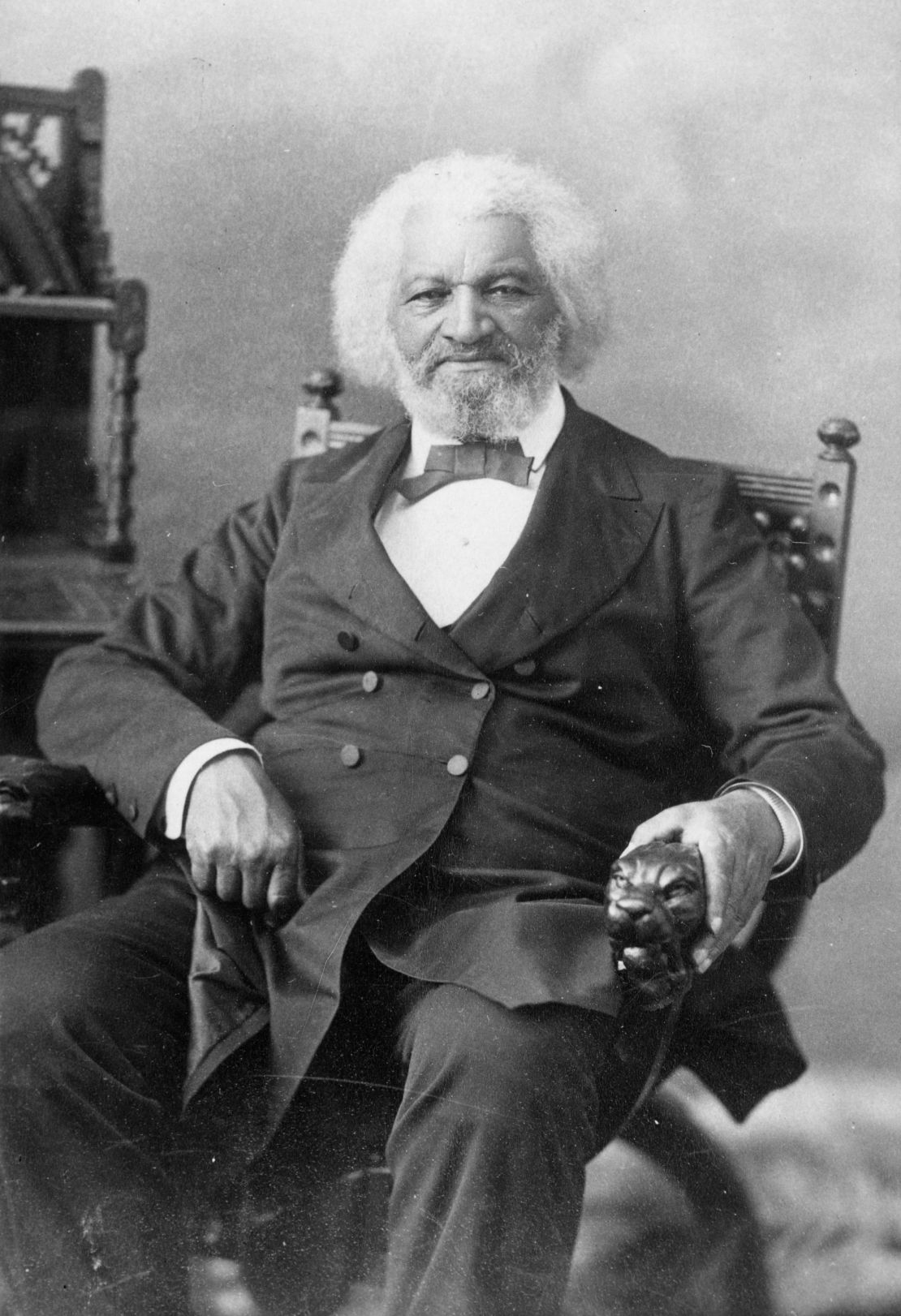

Soon after, when Stanton met the dynamic Susan Anthony, a lifelong relationship was forged. The duo, commonly referred to as the “foremothers” of women’s suffrage, likely didn’t understand the travesty of abolitionist Frederick Douglass being the sole African American invited to Seneca Falls. (No black women were among the hundreds discussing women’s rights.) True, he had been helpful to their cause, particularly suffrage. “The case is too plain for argument,” he wrote. “Nature has given woman the same powers, and subjected her to the same earth, breathes the same air, subsists on the same food, physical, moral, mental and spiritual. She has, therefore, an equal right with man.”

However, after the Civil War, Douglass saw a necessary political choice. Believing two suffrage efforts were impossible to achieve, he directed his eloquence toward men of his own race rather than females of any race: “When women, because they are women, are dragged from their homes and hung upon lampposts; when their children are torn from their arms and their brains dashed upon the pavement; …then they will have the urgency to obtain the ballot.” Feeling betrayed by their ardent champion, Stanton and Anthony did not hide their bitterness.

While Stanton was home raising five children, Anthony was delivering her friend’s take-no-prisoners speeches at rallies coast to coast. Across the years, they were dauntless, pulling no punches. Among a host of other tactics, they published a women’s newspaper, Revolution, where, in addition to advocating for women’s votes, they also went on record opposing the 15th Amendment.

Though they split with Douglass, broadly speaking, the pair understood the importance of unity. And even with that in mind, they worked zealously for almost half a century without achieving their goal.

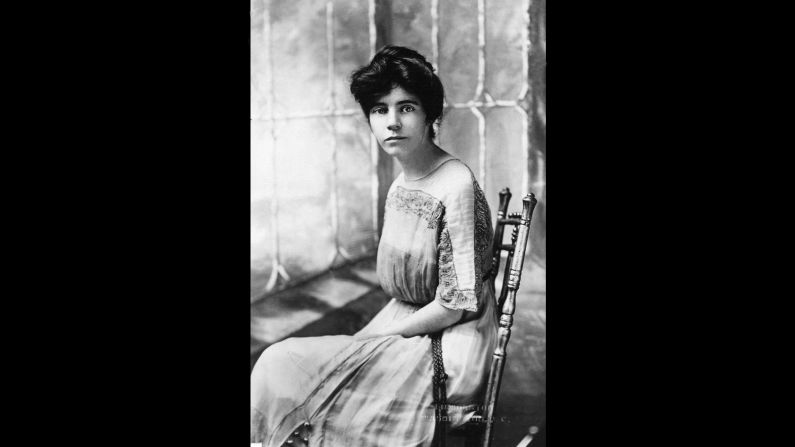

Fast forward to early 20th century London, where more militant protesters (humiliated as “Suffragettes” by a British newspaper, originating the term) were breaking windows, burning buildings, and more. Among its followers was a 25-year-old American student, Alice Paul.

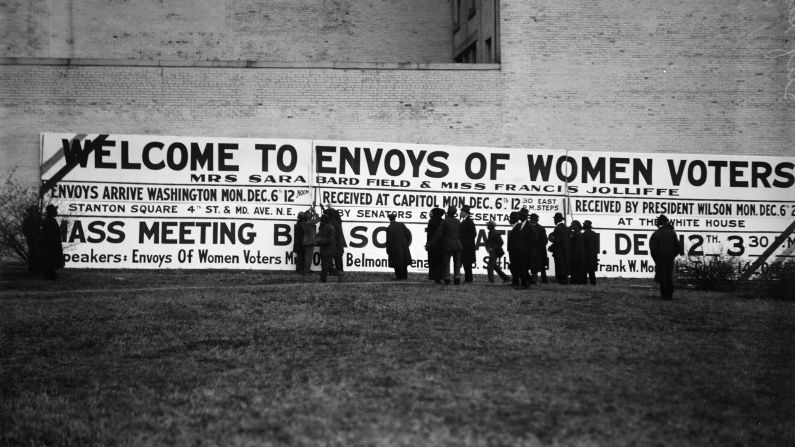

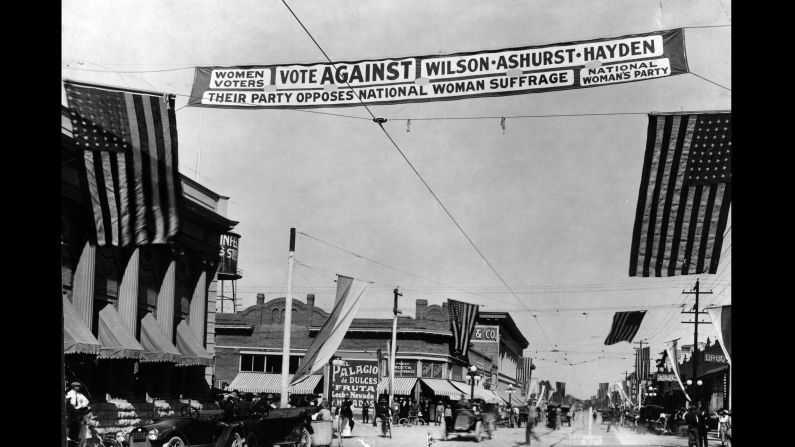

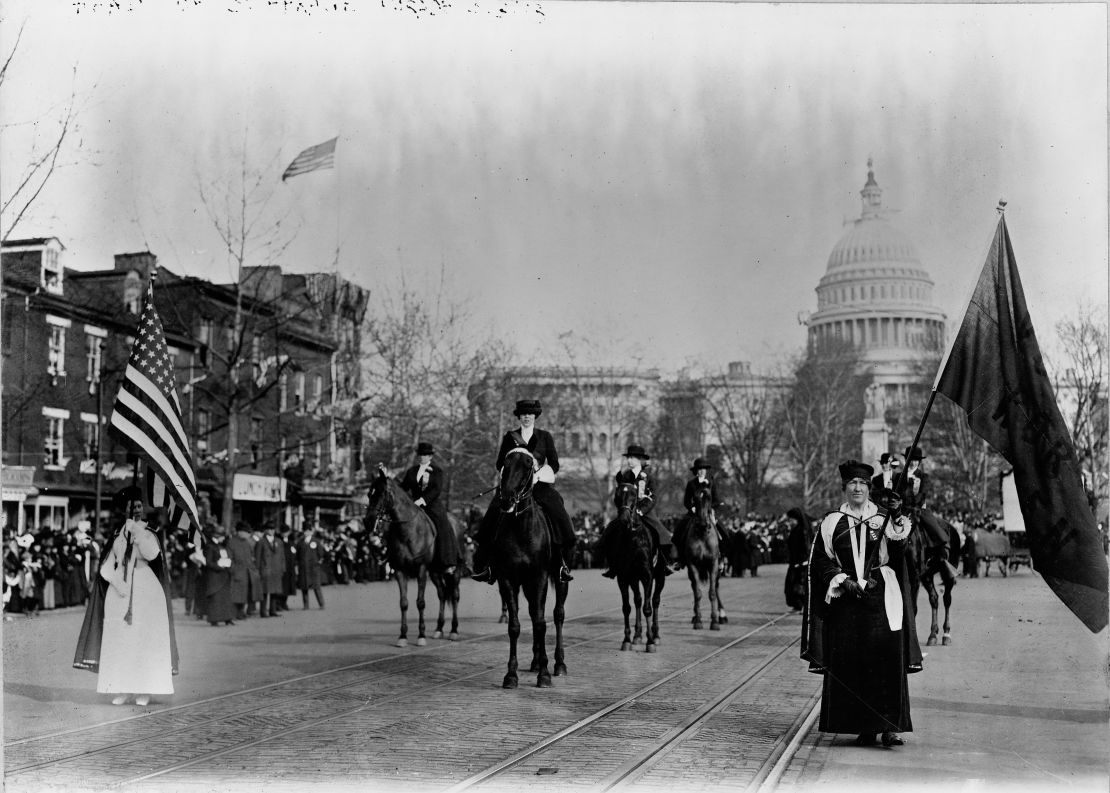

Back home, Paul and firebrand Lucy Burns organized a march, the first large US protest for political purposes, with half a million spectators along the route from the Capitol to the White House. Although the planners announced that all women were welcome, members from the South declared they would not march with the National Association of Colored Women.

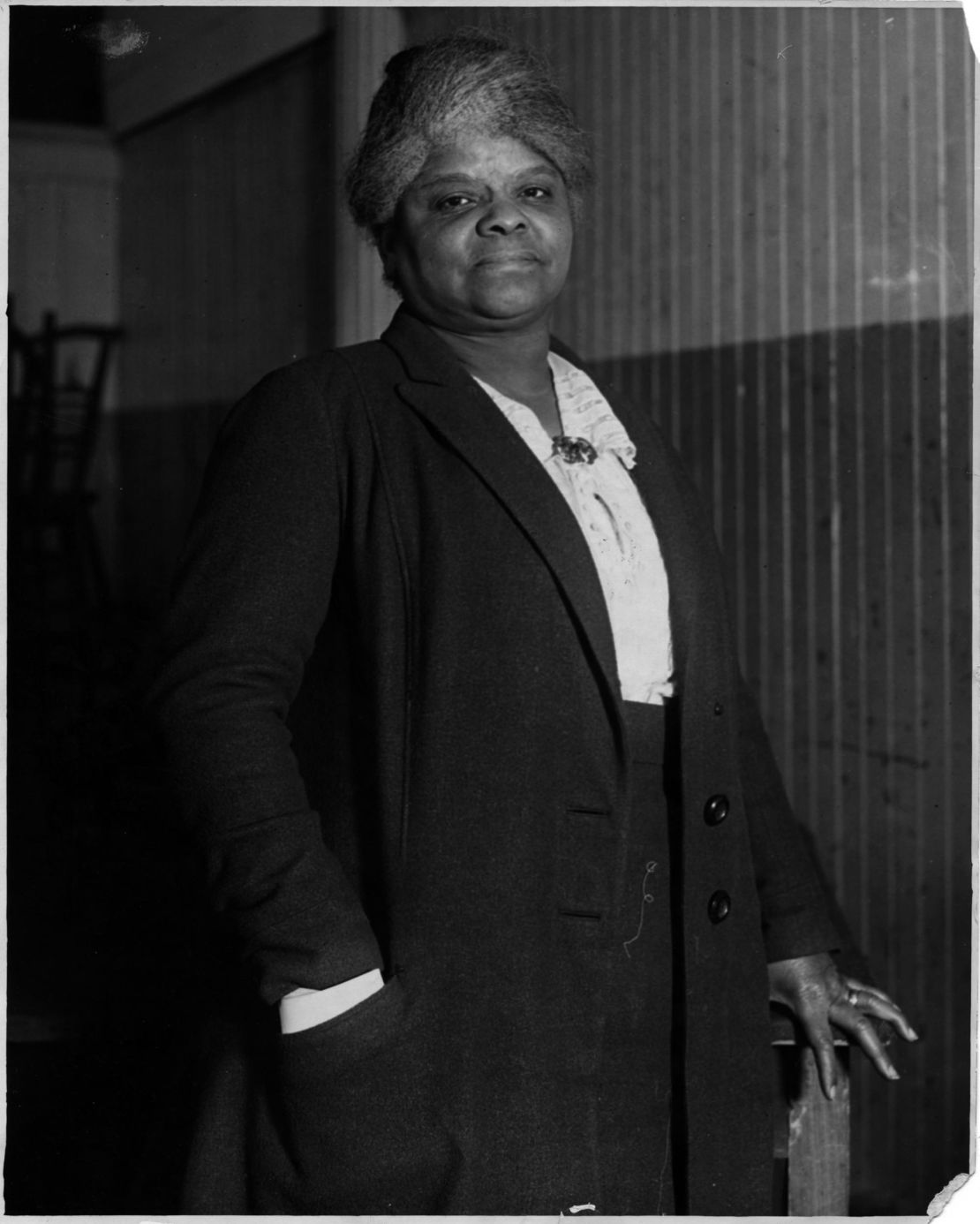

The compromise was to segregate the demonstrators, with white women, then men, then “colored” women in the line. Ida B. Wells, a world-class journalist and fervent anti-lynching reformer, was an indefatigable critic of the segregation. After the parade began, she advanced to the front section. More than a hundred marchers were hospitalized after enraged men hurled trash and bottles at them.

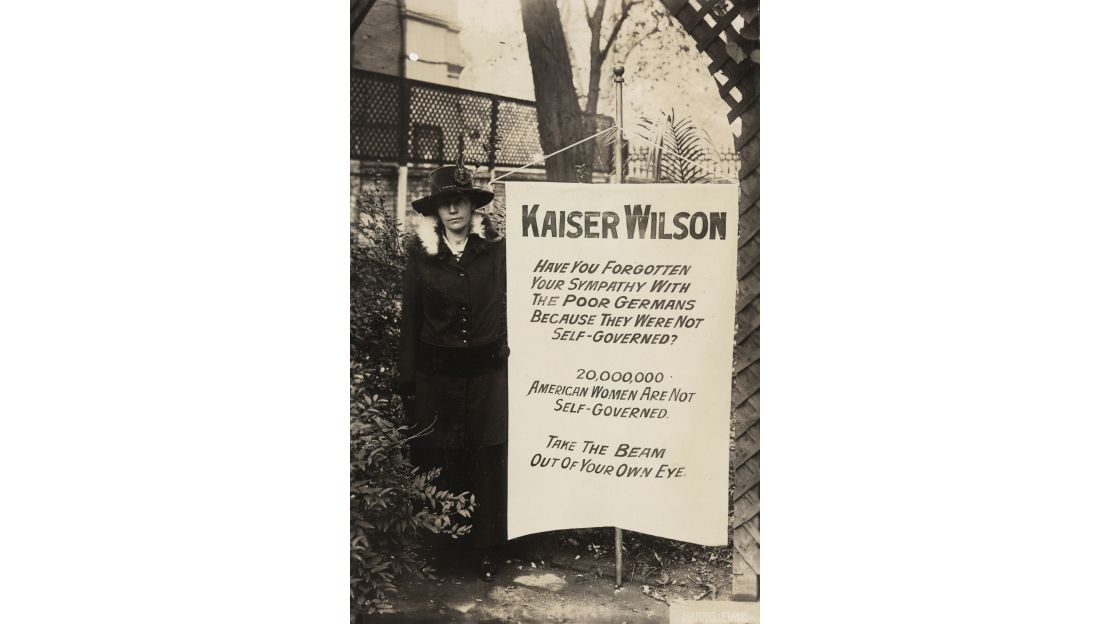

Another ingenious idea became an iconic image of the suffrage insurrection. In 1917 and 1918 (in the middle of WWI) Alice and Lucy organized one thousand (all white) “Silent Sentinels,” the first people to ever picket the White House. For 18 months, regardless of the weather, they stared down threats, taunts, and violence.

After six months, arrests began. Pushing the edge, Paul produced a banner with President Wilson’s own slogan, used to advertise war bonds: “The time has come to conquer or submit.” Incarcerated, she began a hunger strike that spread to other Sentinels. Doctors threatened to ship her off to an insane asylum and force fed her – an excruciating and humiliating ordeal. But the mistreatment galvanized public sympathy, creating momentum for the cause.

After a social movement eternity, in August of 1920, the 19th Amendment became law, guaranteeing that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged… on account of sex.”

Getting the vote was huge, but only the beginning. Women of color in much of the country would not be able to cast a ballot until decades later, when the Voting Rights Act challenged literacy tests and most poll taxes. (Barriers still exist, with gerrymandering and voter suppression.)

Still, race was but one divisive point within the movement. Another was tension with a more moderate, maternalistic approach – typified by satirical cookbooks with recipes like “Pie for a Suffragette’s Doubting Husband” and “Hymen Cake.” Women vowed to use the vote to “clean up” both “dirty politics and equally dirty city streets,” which included defending the rights of accused prostitutes, even as male politicians established a red-light district. Of course, with the lights on or off, men held sway over their wives’ bodies in a struggle that, astoundingly, continues now. Their power encompassed marital rape, beating, requiring or forbidding abortion, and more.

For years, women who could exercise their right to vote continued to be de facto bound to their husbands’ authoritarian choices, biases… and for all practical purposes, their votes. This is personal for me. During the 1950s and 60’s, it was impossible to imagine my mother not yielding to the choices she perceived my father would cast when in a private voting booth.

Women are the majority of voters

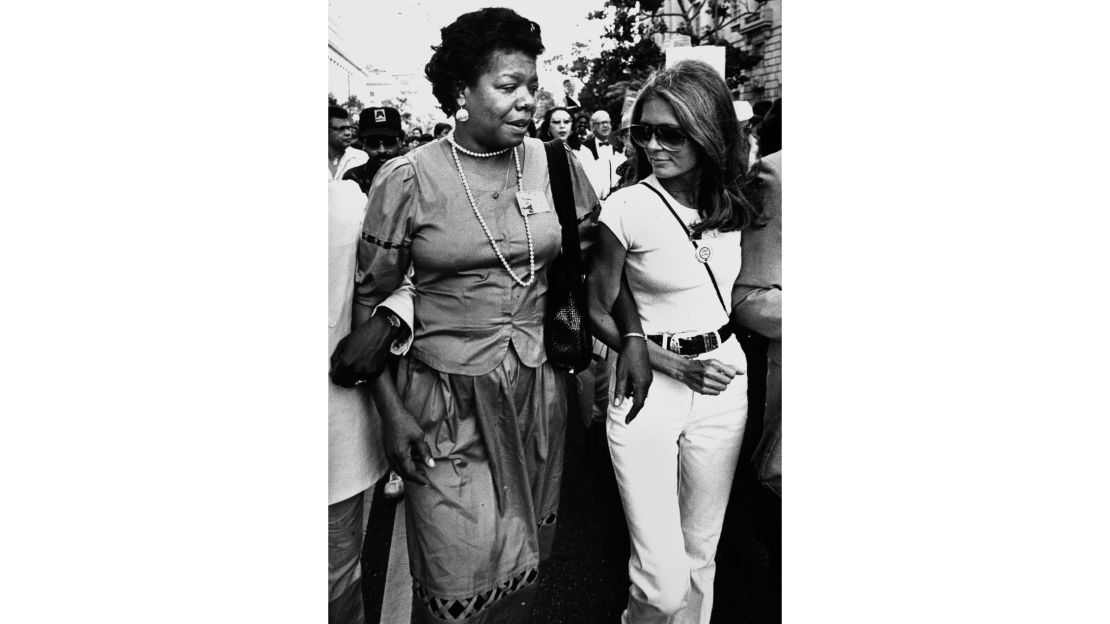

Fortunately, feminism took a major leap forward in the 1970s. Before reforms crept into Texas, I was aghast to meet a woman keeping her maiden name when she was married; or, worse, living in unwed sin. But marching for women, inspired by iconic feminist Gloria Steinem, became a way to express myself and be met with tears of gratitude or tear gas. It took guts. Like the organizers at Seneca Falls, as Steinem opened up the world for women and met incalculable resistance, she knew that every action was a tradeoff.

Today, women are the majority of voters, casting ballots at larger rates than men. (“Larger” means really larger: they’ve been outvoting men for almost three decades, by a margin of nearly 10 million. The issues they are facing at the polls are similar to those that animated – and divided – their foremothers. Fully 69% of women, compared with 56% of men, say the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities is very important, according to the Center for American Women in Politics. Likewise, women (52%) compared with men (38%) say abortion is very important to their vote.

After a trailblazer feminist was defeated despite her landslide popular win, and a misogynist who carried the electoral college was freshly sworn in, American women took to the streets as had their suffragist forbears. January 2017 was a bookend to Alice Paul’s January 1913 demonstration.

Organized by four brilliant activists, the 2017 Women’s March was the largest protest in US history, with throngs of over a million across the nation. Countless others in some 60 nations joined to the chorus of the concerned, the resistance to the coming political and moral nightmare. Tens of thousands waved placards with cheeky messages like “Fight Truth Decay,” “We Are Not Ovary-Active,” “A Woman’s Place Is in Your Face,” and “Viva La Vulva.”

Detractors who had a field day when there was discord among the leaders of this year’s march may not realize that it’s common, and chronic, for movements to experience tensions. We forget that MLK watched his back while moving forward, as Stokely Carmichael, Malcolm X, and a legion of others pulled away and took him on.

In contrast to the Declaration of Sentiments drafted by bonneted ladies, the Unity Principles of the 21st-century protest embrace the full spectrum of Americans. Their central goal is radical solidarity, made possible by “the connected nature of our struggles.”

Today, beyond protesting, women’s civic engagement includes running for office. With her candidacy, Hillary Rodham Clinton did indeed drive another stake into the glass ceiling, creating a chasm of a crack – one through which, two years later, more than 42,000 women have poured. Susan Anthony said her work would not be finished until women held office. Her dream is coming to pass.

But unlike the quest for women’s suffrage, we must understand that the broad differences among us are paradoxically essential to “a more perfect union.” The power of diversity is achieving long-overdue traction.

Get our free weekly newsletter

I like to imagine that Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Anthony, Alice Paul and Ida B. Wells will be watching this centennial year with proud amazement.