Better relations with China used to be a bipartisan issue in Washington.

Beginning with Richard Nixon’s history-making visit to Beijing in 1972, subsequent administrations – both Democrat and Republican – worked to improve relations with Beijing.

Democrat Jimmy Carter formally recognized the People’s Republic of China over Taiwan, Republican George H.W. Bush maintained dialogue with Chinese leaders in the years following the Tiananmen Massacre, and Democrat Bill Clinton supported China’s membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO).

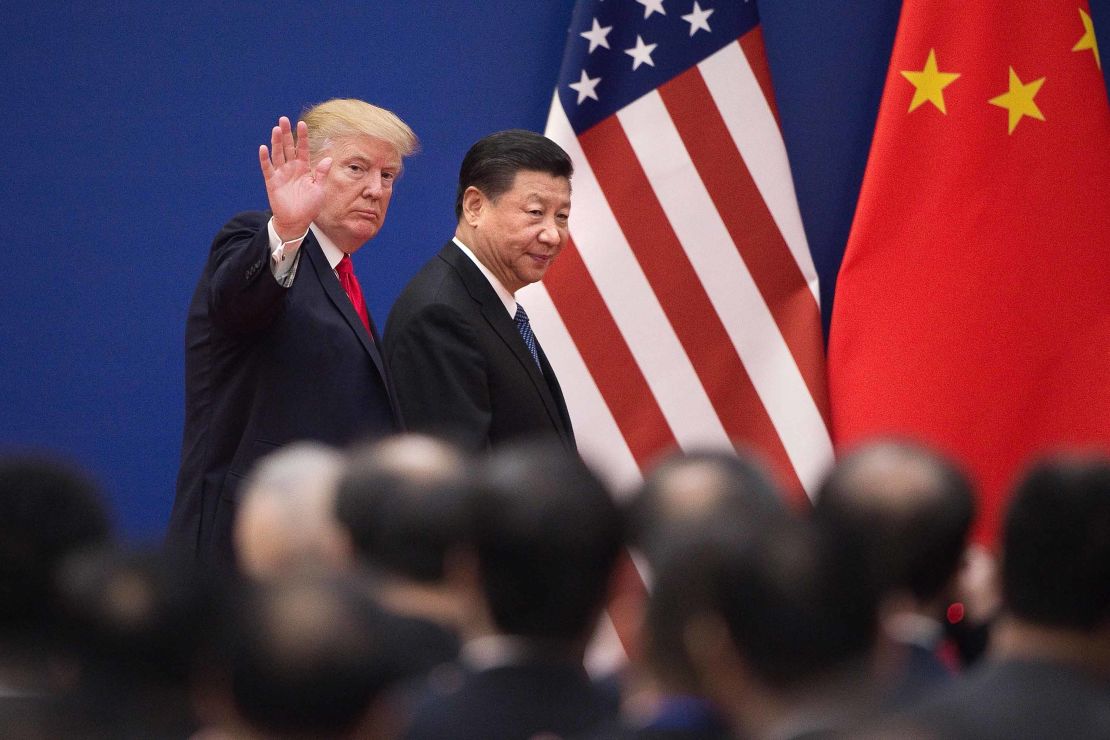

That sense of steadiness and dependability has begun to unravel during President Donald Trump’s time in office. This week, he ramped up a crackdown on Chinese telecoms giant Huawei, amid a worsening trade war with Beijing that is causing economic hardship on both sides.

But while there are many topics where Trump is an iconoclast, out of step with some of his Republican colleagues, let alone the Democrats, this is not it. Bipartisan consensus has swung hard against Beijing in recent years, with some opposition lawmakers in Washington even calling on Trump to take a harder approach.

“There is a broad hawkishness on China that straddles left, right, and center,” said Patrick Lozada, China director at the Washington-based strategic advisory firm Albright Stonebridge Group (ASG). “The problem with this consensus is that in the absence of a credible counter-argument, the actual facts on the ground can sometimes be lost as people compete to see who can be more hawkish.”

Trade war

When Trump introduced new tariffs on Chinese products last year, there were complaints from top Democrats – that he didn’t go far enough.

“The United States must take strong, smart and strategic action against China’s brazenly unfair trade policies,” Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi said at the time. “Yet, today’s announcement is merely a start, and the Trump Administration must do much more to fight for American workers and products.”

Even today, as the expansion of those tariffs have started to bite both consumers and manufacturers at home, offering a tantalizing attack line for Democrats in 2020, criticisms from those in the party’s leadership are of Trump’s execution, not his target.

“We should not be having a multifront war on tariffs,” Democrat Senator Chuck Schumer said this week. “I would focus everything on China. And get the Europeans, Canadians and Mexicans to be on our side and focus on China. Because they are the great danger.”

On Trump’s side of the aisle, voices critical of his deal have been outweighed by Republicans wanting to take an even harder line on China – even as many sought to rein him in on expanding tariffs against European allies.

“The President is right to hold China’s feet the fire on this,” Senator John Barrasso told CNN on Wednesday. “They wouldn’t be negotiating at all if it weren’t for what the President has done … The President has his own timeline. I support what he is doing.”

Broad front

“I’m hard-pressed to think of another consensus in American foreign policy that’s moved as far and as fast as the US consensus on China,” Richard Hass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, a New York-based think tank, said in February.

“People have grown weary of Chinese trade practices, of technology theft. But it’s also a reflection of what’s going inside China … with the treatment of the Uyghurs, the abolition of (term) limits by the president. And it’s also because of strategic concerns such as the South China Sea and what China has done there.”

Lozada, the ASG analyst, said that “Beijing has failed to grasp the changing nature of US politics and the growing concerns about the slow pace of reform in China. When President Trump took office, they regarded him as a transactional businessman without taking serious his remarks about trade on the campaign trail and growing skepticism of China’s role in the global economy at all levels.”

Bipartisan China hawkishness isn’t only hurting Beijing on trade either.

Human rights, often an overlooked topic in relations with Beijing, have come back to the fore, along with calls for punitive sanctions that would further weaken China’s economy in the middle of a trade war.

This week, leading Hong Kong democrats were on Capitol Hill to testify before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), a bipartisan panel which issues an annual report on the state of human rights in China and has grown in influence under the Trump administration.

In his opening remarks, CECC chair James McGovern, a Democratic congressman, said he believed “it is time for the United States to consider new and innovative policies to support the people of Hong Kong.”

McGovern and others have suggested Washington review the US-Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992, under which it treats the city as a separate customs territory to the rest of China, so long as Hong Kong remains “sufficiently autonomous.” Suspending Hong Kong’s special status could devastate the city’s economy and also hit Beijing hard, given its reliance on Hong Kong’s financial sector.

CECC members, including Republican Senator Marco Rubio, have called for China to be sanctioned under the Magnitsky Acts for its oppression of the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang, where hundreds of thousands if not millions of mostly Muslim people have been detained in “re-education camps.”

The Magnitsky Acts, which impose visa sanctions and asset freezes on alleged human rights violators, were originally introduced to go after Russia and have since been expanded to target officials from Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, and other countries.

A bipartisan group of lawmakers, led by Rubio, have called for China to be added to the list. Doing so would strike a major blow against the finances and freedom to travel of top Chinese officials, but would also torpedo any hopes of improving relations with Beijing.

Dangers of further split

Despite widespread skepticism and hostility towards China in Washington today, better bilateral relations in the past paid off for both countries. China’s economy exploded after it entered the WTO in 2000, and the US has long enjoyed the benefits of cheap Chinese manufacturing.

The chances of relations reaching a breaking point and turning into an open conflict are slight, but very real. US military leaders have expressed alarm over China’s moves in the South China Sea and towards Taiwan, as Washington has ramped up its own military engagement in the region, something Beijing regards as a provocation.

Taiwan has bought weapons from the US and lobbied for even greater support from Washington. The island’s de facto independence from China has always been guaranteed to some extent by a belief that the US may come to its aid in a military conflict with Beijing.

While relations are unlikely to sour to the point of actual conflict there is a risk of a new Cold War developing, with other nations forced to choose sides.

That could create a bloc allied against Washington, something that it has not faced since the height of the original Cold War. As commentator Henry Luce wrote in December, better relations between Washington and Beijing under Nixon helped exacerbate the Sino-Soviet split, one factor which resulted in the USSR’s eventual collapse.

“Mr Trump is triggering a ‘reverse Nixon’,” Luce wrote. “Decades of convergence is going into reverse. It is happening at a speed that is taking even Americans by surprise.”

That was five months ago, and things have only sped up since then.