The first thing Harmony Allen remembers after her rape is standing in the shower.

“I didn’t even remember how I got back to base, everything just seemed like a blur. When I got in the shower, I saw the runs of blood just roll off me,” Allen told CNN. “The shower water turned red.”

Almost 17 years later, Allen would come face to face with her rapist in a military courtroom. He would be tried, found guilty of rape and jailed. Then, a 2018 decision by a military appeals court in another case would eventually set her attacker free.

It is a decision she and a bipartisan group of lawmakers are fighting to change today.

Allen was 19 years old, just three months into her radiology technician training at Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas, when a course instructor raped and beat her on August 25, 2000.

That night, Allen was at a club on base where Air Force instructors and students ate and drank. After other instructors left, Master Sgt. Richard Collins lingered.

“When he came over to start talking to me, that was weird in itself,” Allen said. “Because they’re not allowed to talk with students.”

Master Sgt. Collins appeared intoxicated. His voice was loud, his movements, clumsy. When Collins said that he was going to drive home, Allen, who doesn’t drink, stepped in and offered to call a taxi or a base shuttle.

“In the army, it’s our battle buddy. You always look out for your battle buddy,” Allen said. “In the Air Force, it’s your wingman.” Allen later wrote in court documents that she thought she was being a “good wingman.”

When Collins declined a taxi and shuttle, Allen offered to drive him home.

He accepted.

Moments after Allen helped Collins through his front door and into the foyer, he pinned her against a wall and pressed his forearm into her chest.

When she yelled and resisted, adding that she was engaged to be married, Collins threw her to the floor.

Allen’s head split open.

As she regained consciousness, Allen fought and squirmed beneath him. Collins punched her in the face.

Her eyes fixated on a family photo of Collins with his wife and children.

“I looked at that picture the whole time he was raping me.”

When the case went to trial more than a decade later, the nurse who initially examined her in August 2000 still recalled the brutal details of the attack.

After she finished Allen’s rape kit, the nurse had her rushed to Sheppard Air Force Base Emergency Room.

The nurse testified that out of 200 examinations, she only had to do that once in her career.

“I was the worst she’d ever seen,” Allen said. “She still remembered my case because I was the only case that after she did the rape kit she had to send it on to a trauma center for the beating I took during the rape.”

‘Not a case of he-said, she-said’

Master Sgt. Richard D. Collins was tried for the rape of Harmony Allen before a military court on Eglin Air Force Base in Florida in late February 2017. He pleaded not guilty.

During the trial, Allen was asked to point out the man who raped her. “As soon as I looked at him, I vomited” on the witness stand, she said.

A jury of his peers found Collins guilty of rape and sentenced him to 16 ? years in prison, a punishment Allen describes as “very strategic.”

“It took me 16 ? years to get that justice,” she told CNN.

But he was released after serving just two years of his sentence due to a decision by the top US military appeals court last year.

When Allen was raped in August 2000, it was believed that there was no statute of limitations for military sexual assaults. If there was enough evidence to convict, the verdict would stick – years or even decades later.

That changed in February 2018, when the US Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces found that only a five-year statute of limitations applied to sexual assaults that occurred between 1986 and 2006.

Because Allen was raped in 2000 and Collins was not convicted until 2017, he could appeal his guilty verdict under this new ruling.

On July 23, 2018, Collins’ appeal was granted. His conviction of rape was set aside on appeal, and the sentence was overturned.

Though it took nearly 17 years to get a conviction, she reported her rape several times throughout her military career.

Documents provided to CNN show that Allen reported her attack at least five times to Air Force medical and mental health personnel between 2001 and 2011.

In April 2011, after exhibiting signs of PTSD, Allen showed photos of Collins to her clinical psychologist, an Air Force captain.

“I brought in pictures of him, I said this is who raped me. This is Richard Collins, he’s a master sergeant. I said Master Sgt. Richard Collins raped me,” she told CNN.

Still, an official investigation was not launched until March 11, 2014, after Allen left the military and sought VA benefits for PTSD related to her attack. At that time, she was asked to link her treatment to an event she experienced while on active duty.

It took two years and 11 months, but this investigation eventually led to trial and Collins’ conviction.

“This was not a case of he-said, she-said. There was hard evidence. There were witnesses,” Allen said.

“I fought so hard to get the justice to have him put away for what he did. To have that ripped away after finally getting it is so hurtful and crushing and it just questions my belief in the justice system.”

Collins and his lawyer declined CNN’s request for comment. Eglin Air Force Base’s Director of Public Affairs Andy Bourland confirmed to CNN that Collins continues to live on the base with his wife and children.

Following the dismissal, Allen received a letter from the Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff acknowledging the “damage” that had been done to her and her family. “Please know that I am sincerely sorry for everything that happened to you while you were on active duty,” it read.

In a statement to CNN Friday, the Air Force recognized Allen’s “overwhelming pain and suffering.”

“Ms. Allen will always be part of the Air Force family with continued access to professional helping resources through this difficult time.”

Ultimately, the Air Force concluded, it must comply with the order from the appeals court.

Harmony’s Law

Allen’s case has sparked action from a bipartisan group of House lawmakers.

Rep. Brian Mast, combat veteran and Harmony Allen’s congressman, introduced a bill in her name – “Harmony’s Law” – to close the statute of limitations loophole for rape and sexual assault in the military prior to 2006.

“Harmony’s Law” has 16 co-sponsors, so far – nine Republicans and seven Democrats.

“This wasn’t intended by the military. This wasn’t intended by the Congress or anybody else. Those that have committed these crimes are not going to be set free on the technicality of a falsely created statute of limitations by a court that was not meant to create law,” Mast said.

But at least two sexual assault convictions have already been overturned as a result.

Last month, the Pentagon released a report that estimated sexual assaults across the US military increased by a rate of nearly 38% from 2016 to 2018.

For Allen, her case is emblematic of the military’s sexual assault problem.

“The stats are back up. The conviction rate is back down. And I’m like, yeah, I wonder why,” she said.

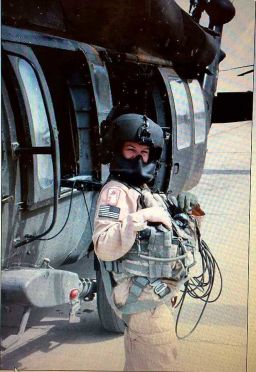

Nearly two decades after her assault, Allen is now an advocate for military women with head injuries as part of the non-profit Pink Concussions.

In 2006, she sustained a traumatic brain injury during a parachute landing. Dr. Phillip M. Holman wrote after her TBI diagnosis that her experiences in the military – “the physical injuries and the stress,” he wrote – “severely exacerbated” her brain injury.

Every other week, she is in treatment for the TBI and for PTSD.

“I had a lot of pride for my country. I wanted to serve. I wanted to defend my country, and that became hard when they weren’t doing what they should’ve been doing to help me when I needed help.”

Reflecting on her treatment at a military hospital back in 2000, Allen said she was handed passes to get out of class and Motrin for her injuries.

“Motrin is the military’s wonder drug,” Allen said. “But no, Motrin doesn’t fix [this].”

CNN’s Veronica Bautista contributed to this report.