For a club so intent on making history, it is perhaps apt that Bayern Munich will at last honor one of the club’s most important figures who helped lay the foundations for its future greatness.

Some 86 years after he was forced out of office by the Nazi regime, Kurt Landauer’s statue will take pride of place at S?bener Strasse, Bayern’s state-of-the-art training facility on the land acquired for the club by the man himself in the aftermath of World War II.

Sculpted by artist Karel Fron, the statue was the brainchild of the Kurt Landauer Foundation, which was established to protect his memory and as a vehicle for social change.

Due to be unveiled in May, the statue cost 70,000 euros ($79,000), with the money raised through donations from fan groups as well as private donors.

“Kurt Landauer laid the infrastructure for all the multimillion dollar players that are at Bayern today,” a Kurt Landauer Foundation spokesman told CNN Sport.

“On the one hand, it shows that there was a club before the golden period of the 70s when Bayern won three consecutive European Cups.

“But we also hope it means that people will now go and learn about how the Jewish people were persecuted under the Third Reich.”

For many football fans, Bayern has always represented success. A five-time champion of Europe, a winner of 28 domestic league titles and 18 domestic cups, the Bavarian club has been a powerhouse of German football for decades.

And yet, it was not always like that. At the time of the Nazis taking power in 1933, Bayern had just won the league title for the first time in its history under a Jewish coach and Jewish chairman.

That chairman was Landauer. Born into a Jewish family in 1884, Landauer began his time at Bayern by playing for the club’s youth team.

His career was cut short when he moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, to train as a banker before returning to Munich where he was elected as the club’s president in 1913.

But his tenure was soon interrupted after he was called up to serve in the German army in World War One.

It was upon his return to the club in 1919 where he resumed his role as president that Landauer began transforming the club from an amateur set-up to a more progressive and forward thinking enterprise.

“Laid the foundations”

“Kurt Landauer laid the foundations to enable Bayern to become what it is today,” club historian Fabian Raabe told CNN.

“He is probably one of the three most important people in the history of our club and that is remembered by the supporters.

“You have to remember, that before him, football had an amateur nature to it. He was an innovator and changed all of that. He made sure the players and coaches got paid properly.

“He was integral to the club’s first title victory in 1932 and everything he built helped pave the way for where we are today.”

READ: ‘The word Jew was not a common insult when I went to school … it is now.’

Just a year after Bayern’s title victory under Jewish coach Richard “Little” Dombi, Landauer’s tenure at the club came to an abrupt end with the rise of the Nazis.

The Nazis branded Bayern a “Jewish club” and Landauer resigned from his position as anti-Semitic legislation began to affect the every day lives of Jews in Germany.

Landauer lost his job at a publishing firm and was forced to seek employment at Rosa Klauber, a Jewish-owned laundry business.

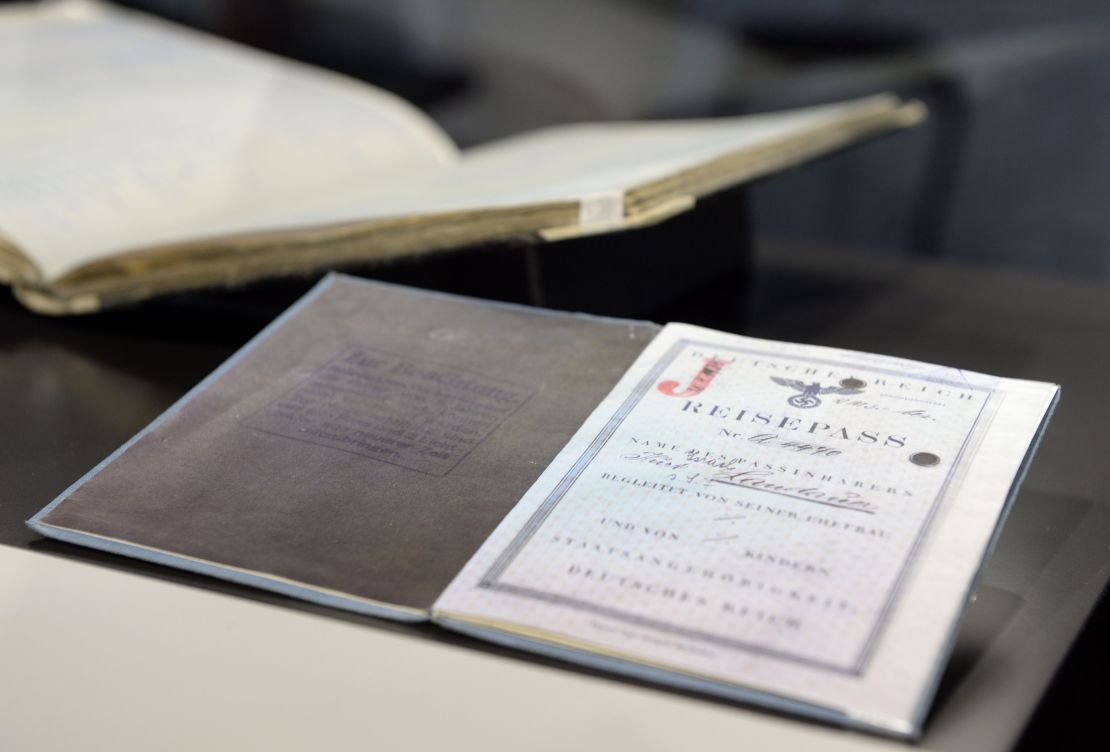

In 1938, the day after Kristallnacht – the rampage of state-sponsored violence by the Nazi regime against Jewish communities – which caused widespread looting and destruction of Jewish properties across Germany and Austria, Landauer was arrested and sent to Dachau concentration camp.

Unlike many others, Landauer was fortunate. He spent 33 days in Dachau, his military service as a solider during World War I securing his release and enabling him to escape to Switzerland in March 1939.

READ: CNN poll reveals depth of anti-Semitism in Europe

While Landauer spent the war years in relatively safety, his family was not so fortunate. His three brothers, Paul, Franz and Leo were all murdered by the Nazis and his sister, Gabriele, was deported and never seen again.

When he did return, Landauer redoubled his efforts to make sure Bayern would be a more professional looking club, securing land for a training ground, advocating payment for players and ensuring the team could compete with its rivals until he left the role in 1951.

His tale has enjoyed a renaissance in recent years. Raabe believes much of that has to do with the way public perception of football has changed since Germany hosted the World Cup in 2006.

He believes that whereas football in places such as Britain has long been seen as part of the country’s social history, the sport was seen more as entertainment in Germany.

“In the 1970s and 1980s there was little time for remembrance or history in Germany,” Raabe said.

“It was really in the early 2000s and then after the 2006 World Cup that things began to change and young people started to ask questions about our history.”

Since then, numerous articles and documentaries on Landauer’s life have become part of the club’s folklore with fans adopting his legacy and publicly celebrating the club’s Jewish background.

“I think that Landauer’s story inspires because of the message it sends,” Raabe says.

“He came back to the place where his family had been killed by the Nazis because he loved the club so much and fans are moved by that.

“They also feel that his legacy has helped make what this club has become and want to tell his story. The ultras are telling fans that they’re proud to have a Jewish story and that if other people have a problem with that then they don’t belong at Bayern.”

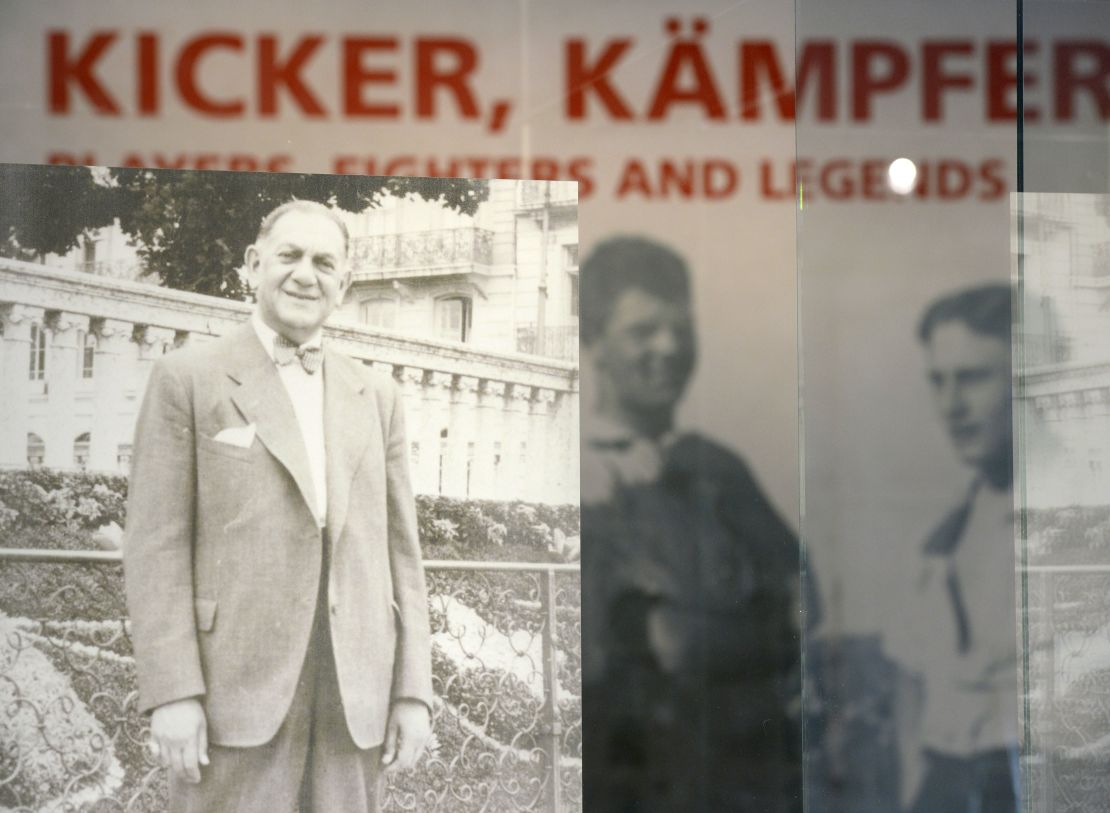

The club has embraced Landauer’s story too, donating money to local Jewish club TSV Maccabi Munich to help build a field named after Landaeur in 2010. There was even an inauguration friendly gainst a Bayern all-star team. There is also an exhibition dedicated to Landauer at the club’s Erlebniswelt museum.

In 2014, Bayern ultra group, Schickeria, was awarded the prestigious Julius Hirsch Award for bringing Landauer’s story back into the public’s consciousness.

The group established a yearly anti-racism soccer competition, known as the Kurt Landauer Cup, and brought banners and choreography into the stadium in his name.

The award, which is awarded to clubs for fighting social exclusion, racism and anti-Semitism, is named after Julius Hirsch, a German Jewish international who died at Auschwitz.

“It’s an important message to the football family that this was someone who made it back and did so with enthusiasm for the club, for the city of Munich where he was persecuted” Michael Linninger of the foundation told CNN.

“It’s a person to identify with at a time where football has changed a lot and those people to identify with are quite seldom.”

Landauer’s story resonates at a time where anti-Semitic attitudes and attacks have increased in Germany.

A CNN survey of seven European countries conducted in Germany, Great Britain, Sweden, France, Poland, Hungary, and Austria exposed the prevalence of anti-Semitism in 2018.

In Germany, the poll found that 55% of those surveyed believed that anti-Semitism is a growing problem in Germany today.

In addition, it also found that 40% of young German adults between the ages of 18-34 know little to nothing about the Holocaust.

Felix Tamsut, a journalist based in Germany who has reported extensively on German fan culture in football, believes the unveiling of the Landauer statue is most timely.

“It’s very significant at this time in Germany when anti-Semitism is on the rise, it’s actually football fans who are trying to fight and stand against it,” Tamsut told CNN.

“It is much more significant than people here can realize, and I’m saying that as a Jew living in Germany, not just a journalist.”

Tamsut believes much of the credit should go to the Bayern supporters, particular the ultras, who he says have been steadfast in their commitment to preserving the memories of the Jewish members of the club who perished in the Holocaust.

“The fact Landauer brought Bayern its first league title was of huge significance but they’ve also celebrated the lives of other Jewish members of the club.

“When you see a choreography inside the stadium about a Jewish Bayern Munich member it makes you emotional. The whole point of the choreography is to remind people that they have a responsibility and they need to act accordingly.”

Visit CNN.com/sport for more news and videos

In life, and now in death, Landauer and Bayern will now be inextricably linked.

There is a quote often attributed to Landauer, highlighting his love affair with the club.

“FC Bayern and I belong together and are inseparable from each other.”

Now it seems that Bayern feels the same way at last.