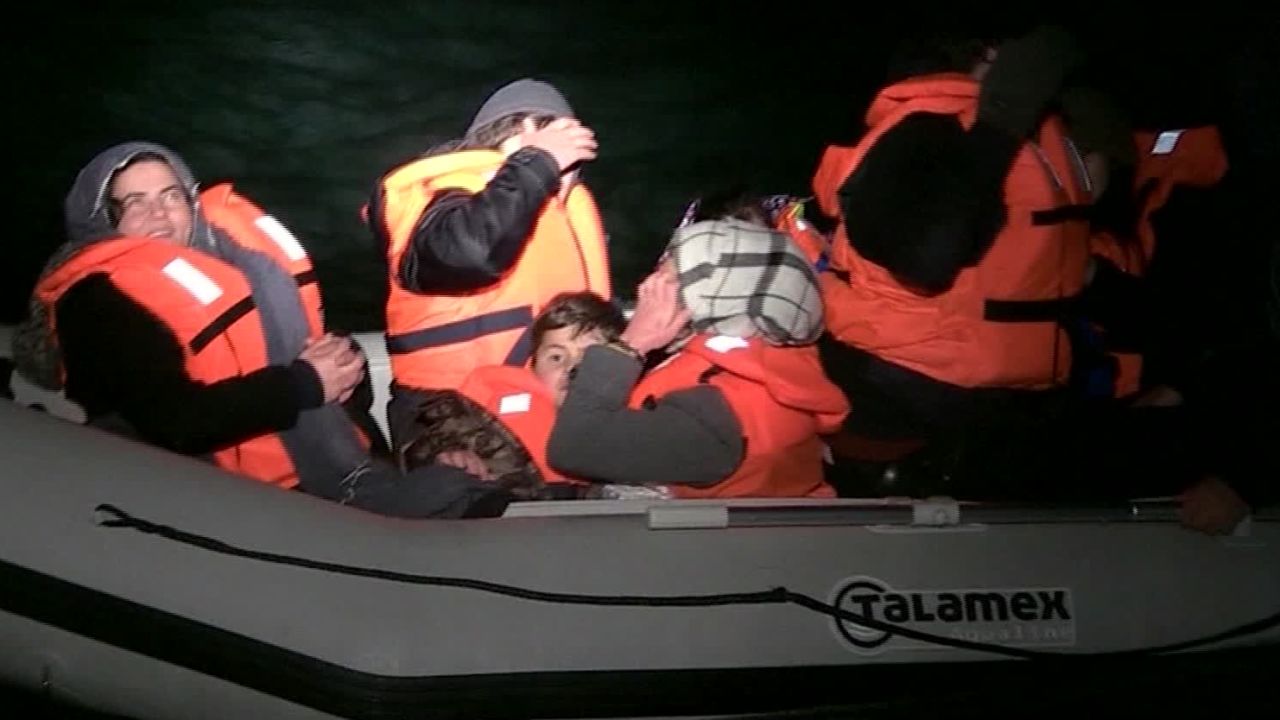

On Christmas Day, 40 people in five separate groups reached British shores after a journey by boat across the English Channel. On Thursday, another 23 were found, the Press Association reported. Then, on Friday, two more boats carrying another 12 people – 11 of them Iranian – were intercepted off the coast of Dover.

Their attempts are not unique – the number of migrants attempting to reach the UK by boat has grown over the past several months.

The spike over the Christmas period is “deeply concerning,” the UK Immigration Minister Caroline Nokes said. “Some of this is clearly facilitated by organized crime groups, while other attempts appear to be opportunistic,” she added, stressing the dangers faced by those attempting to traverse the one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

In a statement on Friday, UK Home Secretary Sajid Javid declared the migrant crossings a “major incident” and “asked for an urgent call with his French counterpart over the weekend to reaffirm the continuing need for the UK and France to work closely together to tackle the problem.”

For many migrants and smugglers, however, the Christmas period is seen as perhaps the most inviting window to reach Britain all year.

“Smugglers are making calculations – and maybe they’re foolish calculations – that borders are less well policed at this time of year,” Leonard Doyle, spokesman for the International Organization for Migration, told CNN.

Dwindling options

This week’s rise in activity across the Channel also reflects the dwindling options facing migrants who hope to make their way to Britain.

Until now, migrants sought to smuggle themselves aboard the trucks that regularly cross the Channel on ferries or by rail from France. But this, they say, has become more expensive, with people-smugglers charging thousands of euros for each attempt.

“The UK has invested a lot of money in protecting the lorry routes” from migrants crossing from France, said Nando Sigona, an associate professor in international migration at the University of Birmingham. “That route has probably been sealed off, or made more difficult to pursue.”

“This is the other option,” he told CNN. “No other alternative is available at the moment … once it becomes visible that it is possible to take this route, others will follow.”

Many of the migrants attempting the crossing over the past several months told UK authorities they came from Iran.

British government figures show that once they get to the UK, Iranians do stand a relatively good chance of being granted asylum. Of 2,500 requests by Iranians in 2017, more than 1,000 were successful. This compares with just over 200 successful requests by Iraqis out of 2,300 applications over the same period.

Economic hardships and political persecution in Iran are undoubtedly creating a “push factor” to leave the country, Sigona said, noting the effect of re-imposed US sanctions on an already faltering Iranian economy.

“You can see people starting to leave the country because of the increase in unemployment, especially among young men,” he said.

Brexit fears

Fears over Brexit could also be at play, experts said. The looming specter of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union on March 29, and the uncertainty it’s creating, may be giving people smugglers an avenue to exploit.

“If people think the borders are going to change, [the smugglers] could be telling people that as a way of getting them to prop up the money,” Doyle, the IOM spokesman, said, which could create a belief that this is the “last chance to get through.”

“That doesn’t mean there is going to be a change – but that’s how people are exploited,” he added. “These people have quite often never been in a boat before, so they don’t know what it means. They’re offered a way [across] and they take it.”

Hadi, a 32-year-old Iranian migrant living in the northern French coastal city of Dunkirk, told CNN earlier this month that “once the UK has left Europe,” he expects the crossing to get harder, “with more policemen.”

Success breeds imitation

And if Brexit provides a ticking clock for those wishing to migrate, anti-migrant sentiment in Europe only accelerates it, according to Sigona.

“A lot of people we are seeing arriving were already in Europe,” Sigona said. “They see gradually the closure of EU states to the people who arrived in 2015, and 2016, and 2017. So they believe this is the only opportunity to reach the UK, which for some of them is the preferred destination.”

A number of European countries have closed their ports to migrants in recent years – including Italy, whose hardline Interior Minister Matteo Salvini made the move in June. “Italian ports are CLOSED!” Salvini tweeted last week after rejecting a request to dock in Italy by a charity rescue ship carrying more than 300 migrants. “For the traffickers of human beings and for those who help them, the good times are over,” he added.

As the number of migrants crossing the English Channel grows, so will the “element of imitation,” Sigona said. “If it works then word spreads around … people start to be channeled towards certain routes because it seems to be working.”

“What will be more interesting will be what happens in the spring and summer,” he added, predicting more attempts to traverse the perilous waters than in previous years – and warning: “it’s more likely that there will be a deadly incident.”