Rachel always thought it was best to hide her religion from her high school students. The trouble started a few years ago when she let slip to a student that she was Jewish.

“I found swastikas scribbled in their textbooks, they drew penises around my name on the blackboard, and they’d yell like ‘Hey, Jew’ at me during class,” said Rachel, a teacher in Berlin. “It became harder… to do my job.”

Rachel, whose name has been changed because of safety concerns, went to her headmaster, and then to the police, but she said neither took her complaint seriously and would not intervene.

She said things got worse. The students saw Israel as a menace, an oppressor of the Palestinian people and viewed her as a stand-in for the Jewish state, she said. They took out their frustration by screaming anti-Semitic slurs at her.

Last year, she decided to switch schools for her own safety. She has not told her new students she’s Jewish.

In a country still haunted by the Holocaust, anti-Semitic incidents in the classroom offer clear evidence that deep wounds haven’t healed. Some Jewish teachers and students say they are caught between a surge of traditional right-wing anti-Semitism and threats from Muslim immigrants angry at Israel.

Unsure of how to deal with anti-Semitism in the classroom, Jewish teachers very often keep incidents to themselves to avoid tipping off their own religious identity, according to Marina Chernivsky, the head of the Berlin-based organization Kompetenz Zentrum für Pravention und Empowerment (or Competence Center for Prevention and Empowerment), which provides counseling to individual and institutions after anti-Semitic and discriminatory incidents.

She recently held a workshop to help Jewish teachers deal with anti-Semitism in their classrooms. Around 20 Jewish teachers attended the session; Chernivsky said it was the first time many of them opened up about the problem.

“It’s not normal to be Jewish in Germany so anti-Semitism is not normal to talk about,” Chernivsky said. “It’s very taboo.”

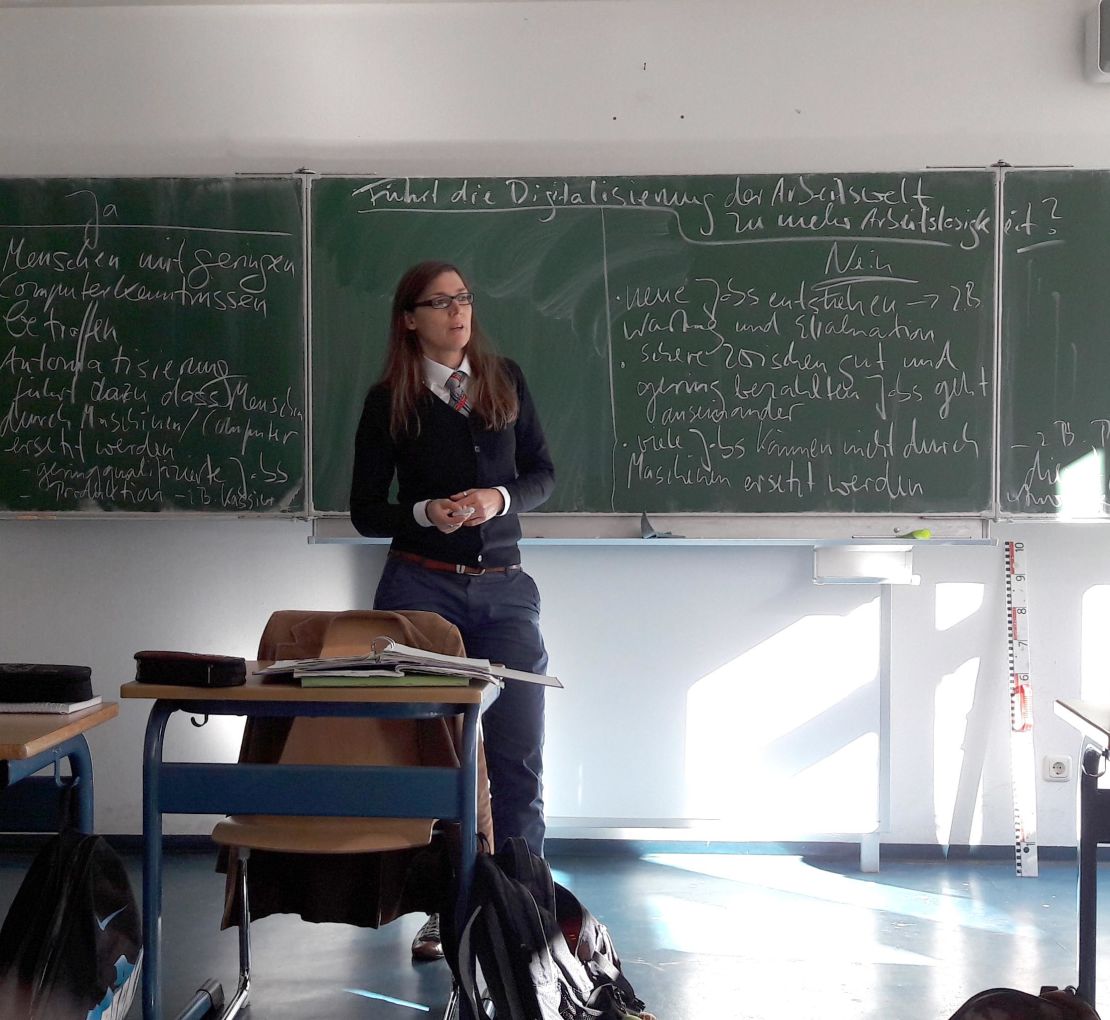

It took history and politics teacher Michal Schwartze years to reveal her religion to her students.

The Frankfurt based 42-year-old said she didn’t feel comfortable teaching about the Holocaust, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or anti-Semitism in Europe without being transparent with her students.

“I don’t say hey I am Jewish, but I make it clear that I am personally affected,” said Schwartze.

A few years ago, Schwartze penned an article in her school’s newspaper encouraging students to stop using the word “Jew” as a slur. She said she took a risk writing the piece, but it raised awareness around anti-Semitism at her school.

“Fortunately, I have colleagues who are sensitive and a headmaster who has an interest in preventing anti-Semitism,” says Schwartze. She cautioned that Jewish teachers who don’t have similar support need to “hide their identity.”

Berlin’s Department of Research and Information on Anti-Semitism (RIAS) said serious incidents affecting Jewish students and teachers in Berlin’s schools doubled from 15 to 30 in 2017 and the rate is on a similar pace this year. RIAS said most episodes still go unreported. Those that were reported included a 16-year-old girl taunted by classmates who chanted “gas for the Jews.” A 14-year-old boy who was bullied, kicked and shot with an air gun because he was Jewish. And a Jewish student at a prominent international prep school who had cigarette smoke blown in his face while his assailants asked how it felt to be sent to the showers.

Nineteen-year-old Florian M?tzschker told CNN he faced so many threats at his Berlin high school that he had to use a separate entrance.

“As a Jew in Germany you feel attacked on all sides,” he said. “There’s no trusting the German government to protect us.”

Career diplomat Felix Klein, 50, was appointed in April to a newly created cabinet-level position: Germany’s anti-Semitism commissioner. He said although anti-Semitic attitudes have long bubbled below the surface in Germany, those views are now exploding into the open.

“The word Jew as an insult was not common when I went to school,” said Klein. “Now it is, and it’s even an insult at schools where there are no Jewish students. That’s a problem.”

Forgetting the Holocaust

German high school students learn about the Holocaust in the ninth grade, around the age of 14 or 15. They’re taught about the state-sponsored murder of millions of Jews and they take field trips to nearby concentration camps. A generation ago, teachers lingered on the events of the Third Reich, making sure to present it to students as part of their country’s heritage. Now, as survivors dwindle and the immigrant population grows, Jewish leaders fear that history is being cleaved from the German experience.

“There’s been an ever-growing tendency on the part of some in German education to universalize the lessons of the Holocaust,” said Deidre Berger, the head of the American Jewish Committee in Berlin. “This was a singular historical event that emanated from Germany, and when German students learn that they need to know that.”

And yet a CNN poll found that 40% of young German adults know little to nothing about the Holocaust. The numbers don’t surprise Saraya Gomis, the anti-discrimination commissioner for Berlin’s education, youth and family department.

“So often in schools, the Holocaust is only treated as something in the past and this has nothing to do with our present,” said Gomis, who is half-German, half-Senegalese. “It’s not enough to just go to concentration camps and say that was a long time ago and now we are good. The result is that students don’t see Jews as living people, just something that happened in the past.”

POLL: CNN poll reveals depth of anti-Semitism in Europe

Guillermo Pineiro, who teaches Spanish and German at a high school in Essen, said the history of the Third Reich is taught at school, but for students “it’s a little more abstract.”

Last year, after an incident where a group of students were caught using Jewish slurs in class, Pineiro decided to reach out to an organization called “Rent-a-Jew,” which finds Jewish volunteers who want to speak about their history and culture.

“It was the first time any of them had ever met someone Jewish,” Pineiro said.

Teachers not equipped

The German government is taking steps to address anti-Semitism in schools. It has dispatched 170 anti-bullying experts to selected schools across the country. Klein said his office is creating a nationwide registry where teachers, administrators, and the general public, can report anti-Semitic incidents. Right now, no such system exists, making it difficult for authorities to understand the scope of the problem.

CNN spoke with dozens of people, including Jewish teachers, students, and parents as well as German government officials and activists. They described a tendency among school administrators to cover up incidents and downplay anti-Semitic bullying. Anti-discrimination commissioner Gomis said many teachers and administrators are ill-equipped to recognize the problem and are more likely to make things worse.

“Many teachers and principals have a huge lack of knowledge when it comes to dealing with anti-Semitism,” Gomis said. “They’re not quite sure how to detect it, and when they do, they’re too busy or stressed to deal with it.”

Although 76% of Germany’s Jews believe anti-Semitism is a problem, 77% of non-Jews in Germany believe the opposite, according to a recent government report. And parents say that makes it hard for administrators to confront anti-Semitism in their own schools.

“If you ask somebody’s who’s not Jewish if there are problems with anti-Semitism in Germany, they would say no way,” said Wenzel Michalski, the father of a 15-year-old who was forced to switch schools after months of anti-Semitic bullying. “They think it’s a Jew making a fuss.”

Michalski is the head of the German chapter of Human Rights Watch. He said his son began attending Friedenauer Gemeinschaftsschule in December 2016. Its motto: “A School Without Racism”.

The grandson of a Holocaust survivor, Michalski’s son told his new classmates he was Jewish.

“He said it was like you could a hear a pin drop,” said Michalski. “His cover was blown. His new friends said you can’t hang out with us anymore because you’re Jewish and the attacks quickly became worse and worse.”

Michalski says his son, who was 14 at the time, was smacked on the head and kicked to the point where he developed bruises. Three months into his stint at the school, a fellow student shot him with an air gun while taunting him with anti-Semitic slurs.

Michalski said school administrators tried to play it off as “boys will be boys,” and were unwilling to do anything about the incident. He ended up pulling his son out of the school three months after he enrolled.

CNN has contacted the school for comment and did not receive a response. In an interview with the German publication Der Tagesspiegel, principal Uwe Runkel defended the school’s actions and said that administrators reacted quickly when they learned what had happened.

Runkel later posted a message on the school’s website detailing the steps he took to address anti-Semitism, which included reporting the incident to Gomis’ office and hosting group discussions, mediated by trained experts, where students and teachers could discuss how the school should deal with anti-Semitic bullying in the future.

A year and a half later, Michalski says the school still hasn’t taken the issue seriously enough.

“When you see how they react, it’s not surprising that there’s a new generation of kids growing up as anti-Semites,” Michalski said.

Ready to leave?

Five years ago, Germany’s Jews would have never considered moving away from the country, according to Doron Rubin, the leader of Berlin’s Kahal Adass Jisroel community organization. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Germany was in the midst of a Jewish revival – the population had grown to over 200,000, and rabbis were ordained in Berlin for the first time since the Holocaust.

Now, Rubin said, the question of leaving is being discussed again.

“I think the German establishment is surprised to be dealing with anti-Semitism again,” said Rubin. “They thought it was something that’s past, and I think in recent years they’ve understood it’s a broader problem that’s not just going to go away.”

Community leaders in part blame an increase in inflammatory rhetoric from far-right parties like Alternative for Germany (AfD) for changing public discourse. They say it is not only Jews who are targeted by racist rhetoric – Muslim, African and LGBT communities are also affected.

“Right-wing populism plays a huge role in making people feel comfortable using slurs,” says Alexander Rasumny executive director of RIAS. “I think we’re seeing a shift in the thing that can be said in public, and opinions that are socially accepted.”

The neo-Nazi banners and salutes that have appeared at recent far-right protests have alarmed German Jews, but many say the more immediate threat is from parts of Germany’s immigrant population. They say they are often targeted with slurs by Muslims. According to Klein, traditional tools for tackling neo-Nazism are not a solution and he is looking to leaders in the Muslim community for help.

“When we talk about Muslim-originated anti-Semitism, I think we can only win that battle with the help of the moderate Muslims,” Klein said. “Without them, this won’t be a successful fight.”

Some of that work is already underway. Named after a heavily Muslim neighborhood in Berlin, the Kreuzberg Initiative against anti-Semitism (KIgA) sends teaching guides into more than 40 schools across Germany to help counsel young Muslims at risk of radicalization. One of the goals: encourage dialogue among Muslim students and their Jewish peers.

KIgA’s chairman Dervis Hizarci cautions against painting all Muslims as anti-Semitic. Doing so, he said, further alienates young Muslims who may also be facing discrimination in German society.

“We have to make Muslims feel addressed,” Hizarci said. “Fighting anti-Semitism among Muslims can only succeed if we do that together with Muslims. If we talk to Muslims instead of talking about them.”

Peaceful dialogue might be a difficult proposition, especially when many young Jews are determined to defend Israel’s policies. Before graduating last year, Florian M?tzschker said he was one of two Jews at a 1,200-student high school in Berlin’s Wedding district. M?tzschker didn’t come from a religious family, but the more he was threatened, the more he began dreaming of moving to Israel to join the Israeli army.

Last December, he was sitting alone in the school cafeteria when a group of Muslim classmates came up to him and started giving him a hard time about US President Donald Trump moving the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He tried to defend Israel’s claim to the city.

“That’s when they started saying over and over again, ‘We will destroy you’, and then one girl said to me ‘Adolf Hitler was a good guy because he killed the Jews,’” M?tzschker said. “She just kept saying it over and over again. I was in shock.”

He said the comment set him off. He told her she wasn’t allowed to say that. That’s when the group of students started swarming him, screaming “Israel is the murderer.”

“I was really, really scared,” M?tzschker said. “I couldn’t get out, they had me surrounded on all sides. It was like suffocating. I finally broke away, but even the teachers were scared to step in.”

For the rest of the year he spent breaks sequestered from his fellow students and covered his yarmulke under a baseball cap.

“I got through because I kept saying to myself, ‘One day soon, I will be in Israel and this will all be over.’”

Clarissa Ward and Antonia Mortensen contributed to this report from Berlin.

A special edition of CNN talk with Max Foster and Clarissa Ward will discuss the findings of the CNN/ComRes anti-Semitism poll. Watch on CNN International and Facebook.com/CNNI at 12 p.m. GMT.