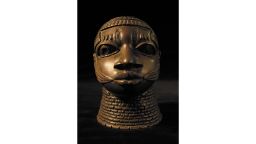

More than a century after British soldiers looted a collection of priceless artifacts from the Kingdom of Benin, some of the Benin bronzes are heading back to Nigeria - with strings attached.

A deal was struck last month by the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) that would see “some of the most iconic pieces” in the historic collection returned on a temporary basis to form an exhibition at the new Benin Royal Museum in Edo State within three years.

More than 1,000 of the bronzes are held at museums across Europe, with the most valuable collection at the British Museum in London.

Nigerian governments have sought their return since the country gained independence in 1960.

Temporary solution

The agreement represents a breakthrough for the BDG, which was formed in 2007 to address restitution claims.

The group comprises of representatives of several European museums, the Royal Court of Benin, Edo State Government, and Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments.

The returns are contingent on the timely completion of a new Royal Museum, adjacent to the Royal Palace that once housed many of the bronzes. Nigerian officials presented plans for the Museum at a BDG meeting in October. A spokesman for the Governor of Edo said that designs are being finalized in collaboration with the Royal Court of Benin.

A spokesman for the British Museum said European museums would play an active role in developing an elite institution suitable for housing exhibits that are considered to be among the greatest ever African artworks.

Follow CNN Africa on social media

“The key agenda item (at the October meeting) was how partners can work together to establish a museum in Benin City with a rotation of Benin works of art from a consortium of European museums,” the spokesman said.

“The museums in attendance have all agreed to lend artifacts to the Benin Royal Museum on a rotating basis, to provide advice as requested on building and exhibition design, and to cooperate with the Nigerian partners in developing training, funding, and a legal framework for the display in a new planned museum.”

Details about which pieces will be returned and how many are yet to be established. Dialogue is ongoing between the parties of the BDG, and the group is scheduled to meet again in Benin City next year. The present agreement notes that Nigerian partners have not ceded claims for permanent restitution, and officials remain determined to secure the bronzes on a permanent basis.

“We are grateful these steps are being taken but we hope they are only the first steps,” Crusoe Osagie, spokesman for the Governor of Edo, told CNN. “If you have stolen property, you have to give it back.”

Osagie called for greater pressure on European governments to return the bronzes.

Breaking the deadlock

Nigerian claims received a boost with the release of a new report commissioned by the French government that calls for wholesale restitution of artifacts seized during the colonial era.

The report from academics Felwine Sarr and Benedicte Savoy, prompted by President Emmanuel Macron’s 2017 commitment to return African heritage, recommended that items taken without consent should be liable to restitution claims.

Many of the estimated 90,000 artifacts of sub-Saharan African origin held at French institutions could be contested under the report’s criteria.

Sarr and Savoy further recommended that key, symbolic pieces long sought by claimant nations should be immediately returned - including several French-held Benin bronzes.

The report also proposed a series of bilateral agreements between the French government and African states to bypass French laws barring museums from releasing their collections, which have proved a longstanding barrier to restitution. Such agreements would allow for permanent restitution rather than loans.

The French government has responded to the report by announcing an initial 26 artworks will be returned to the state of Benin, with further restitution to follow.

Pressure building

France’s example will increase the pressure on museums across Europe, which has been building on several fronts.

Grassroots campaign groups within European countries are demanding restitution, such as in Germany, where 40 organizations recently signed an open

letter calling for the return of historical artifacts.

The letter prompted German institutions to conduct inventories of their collections to determine which items were acquired illicitly.

There is also growing recognition of the validity of restitution claims from a new generation of political leaders. Leader of the UK Labour party Jeremy Corbyn has said that if elected, his government would be willing to discuss the return of “anything stolen or taken from occupied or colonial possession.”

Several influential private collectors have also taken the side of African claimants, such as British citizen Mark Walker, who voluntarily returned a set of Benin bronzes captured by his grandfather.

Museums are also facing a raft of increasingly determined claims from the governments of dispossessed nations across the world, from sub-Saharan Africa to Greece’s claims for the Elgin Marbles, to Chile’s appeal for Easter Island statues.

Few longstanding observers of a saga that has been taking place since the end of the colonial era expect these matters to be resolved quickly. President Macron’s initial commitment to return just 26 pieces suggests a long term process.

Museums and national governments are likely to resist wholesale restitution, and national laws preventing museums from disbursing their collections will continue to present a formidable barrier.

But if the wheels are turning slowly, they do at least appear to be shifting.