NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope has run out of fuel, and its mission has come to an end 94 million miles from Earth, the agency announced Tuesday. The deep space mission’s end is not unexpected, as low fuel levels had been noted in July.

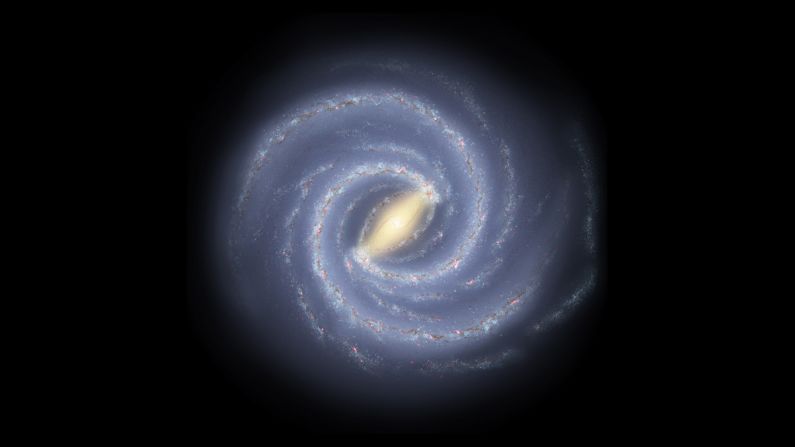

The nine-year planet-hunting mission discovered 2,899 exoplanet candidates and 2,681 confirmed exoplanets in our galaxy, revealing that our solar system isn’t the only home for planets.

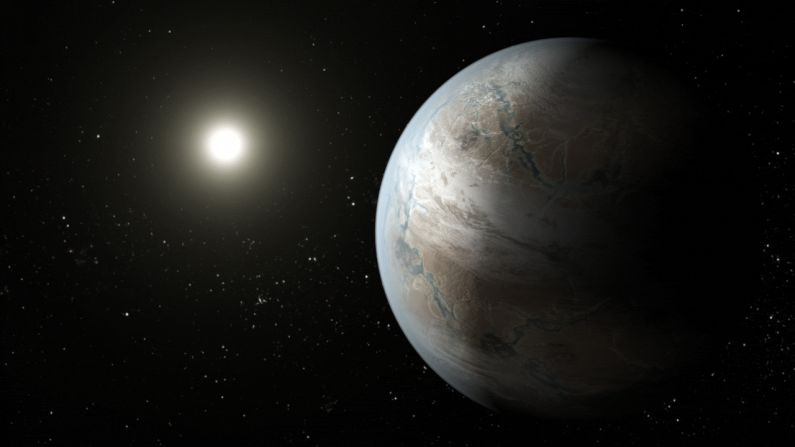

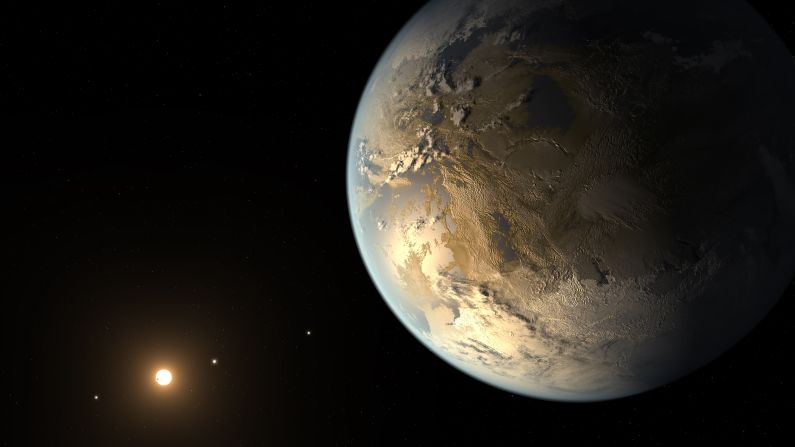

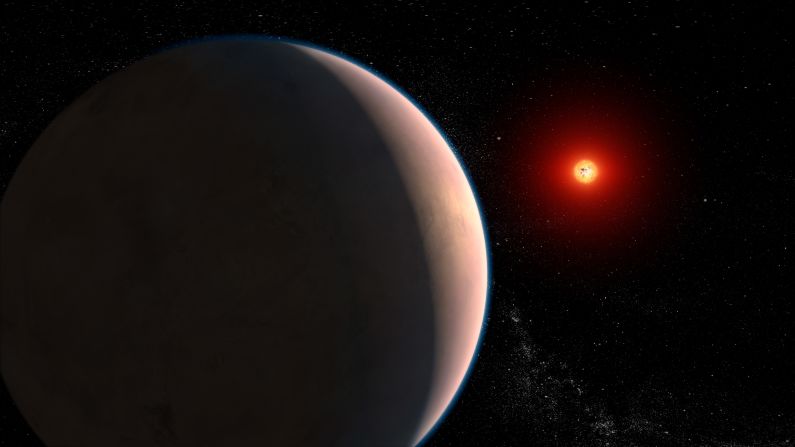

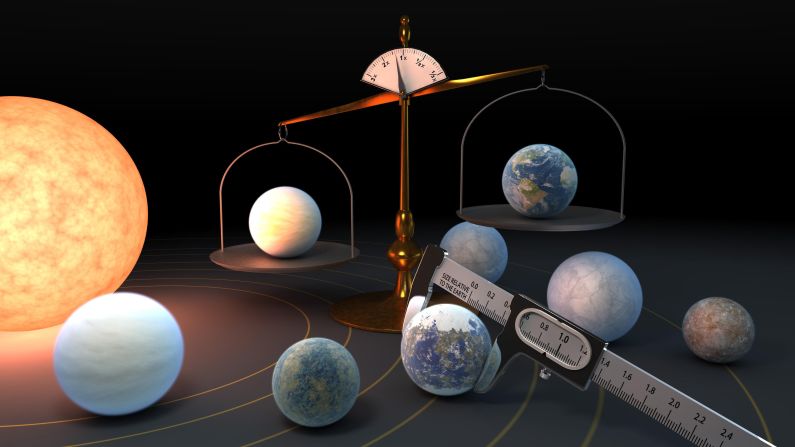

Kepler allowed astronomers to discover that 20% to 50% of the stars we can see in the night sky are likely to have small, rocky, Earth-size planets within their habitable zones – which means that liquid water could pool on the surface, and life as we know it could exist on these planets.

The final commands have been sent, and the spacecraft will remain a safe distance from Earthto avoid colliding with our planet.

“As NASA’s first planet-hunting mission, Kepler has wildly exceeded all our expectations and paved the way for our exploration and search for life in the solar system and beyond,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “Not only did it show us how many planets could be out there, it sparked an entirely new and robust field of research that has taken the science community by storm. Its discoveries have shed a new light on our place in the universe and illuminated the tantalizing mysteries and possibilities among the stars.”

The Kepler mission was named in honor of 17th century German astronomer Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion.

Kepler, the telescope, reached more than twice its initial target, accomplishing original mission goals and seizing unexpected opportunities to answer questions about our galaxy and the universe, according to Charlie Sobeck, project system engineer at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

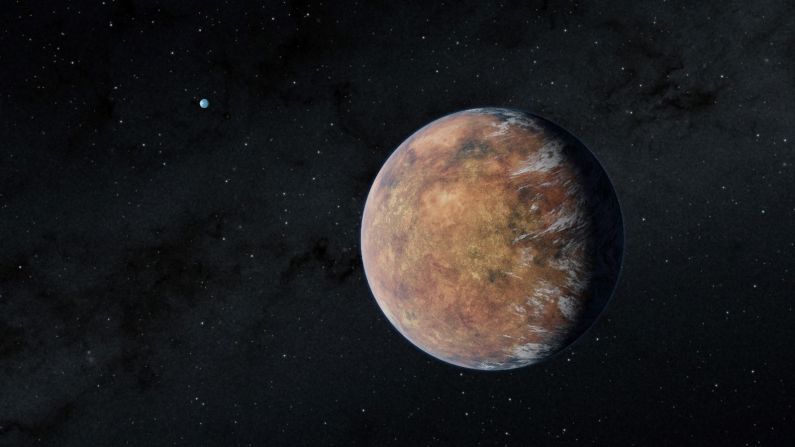

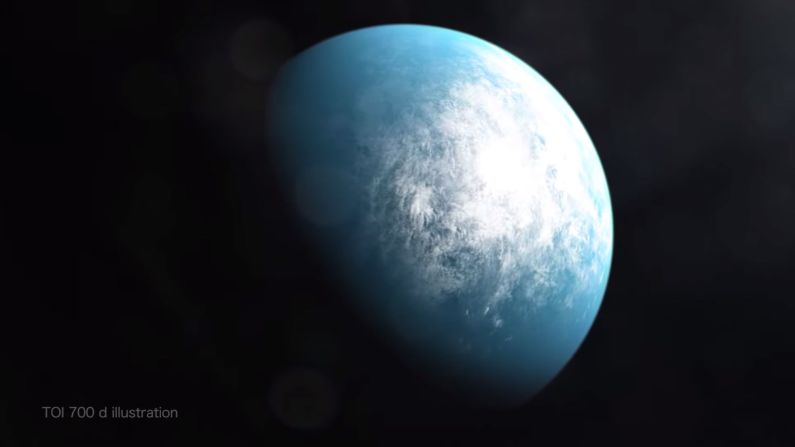

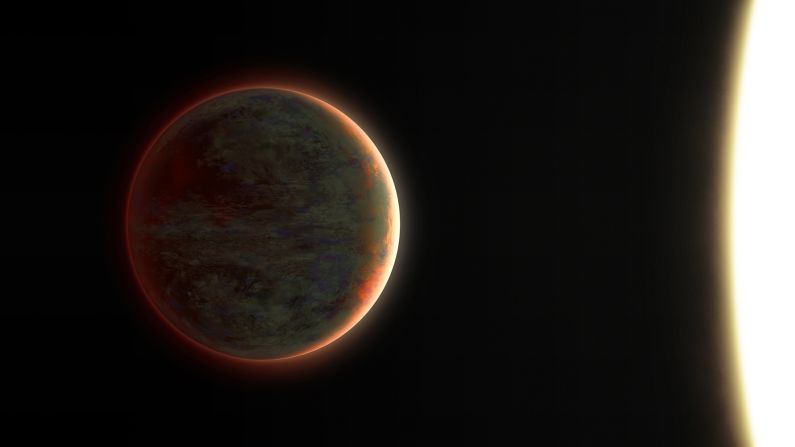

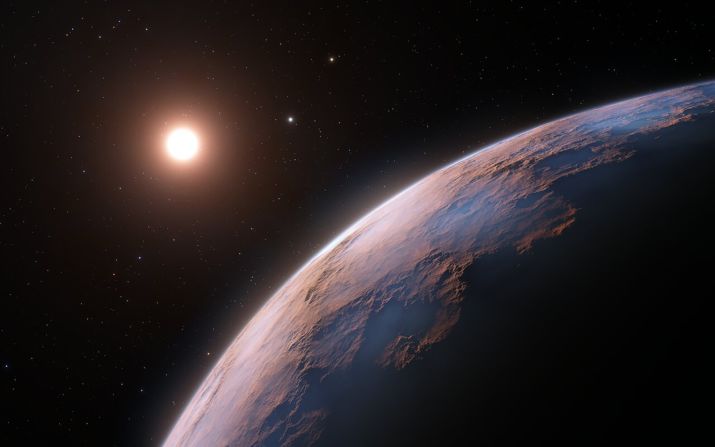

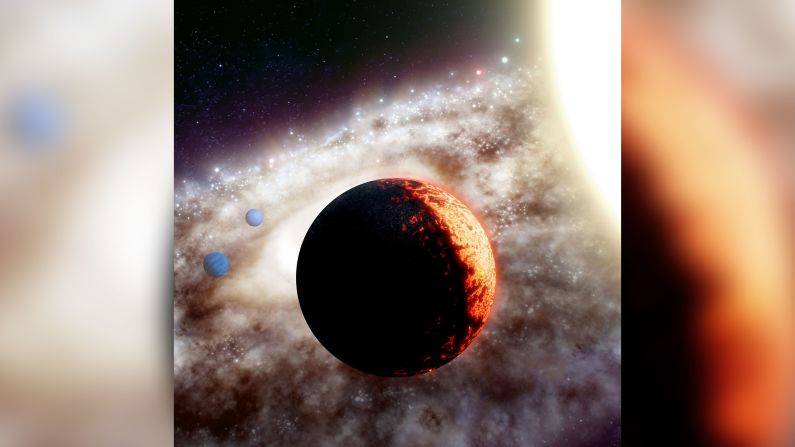

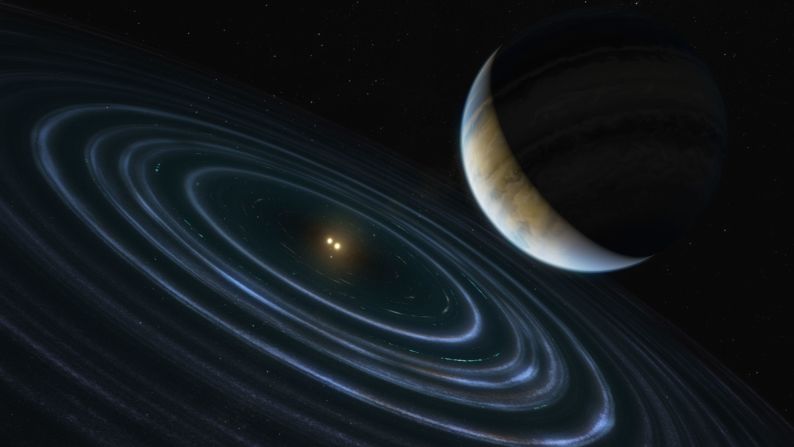

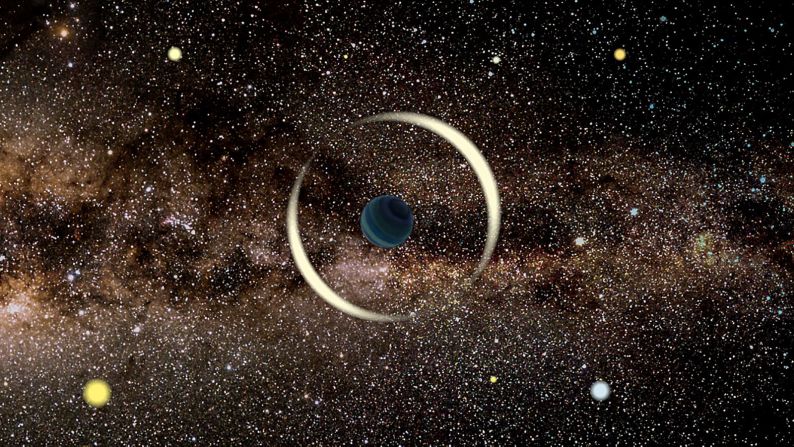

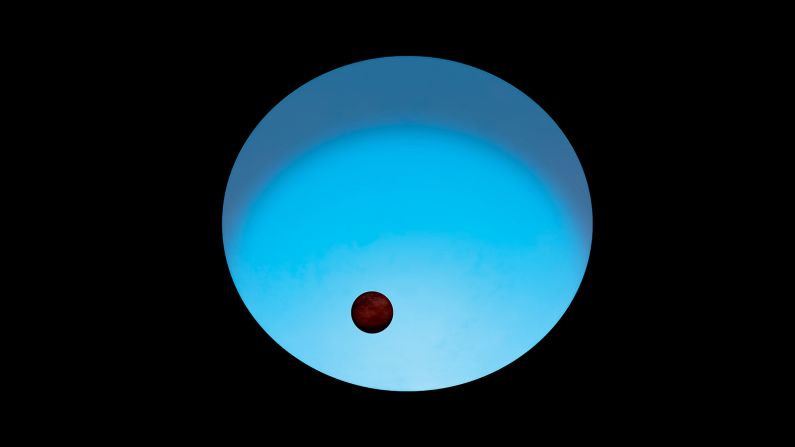

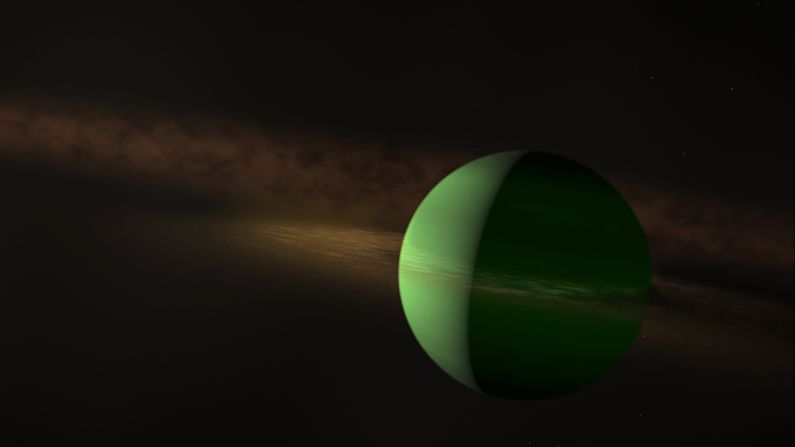

Weird and wonderful planets beyond our solar system

Every bit of scientific data collected by Kepler was transmitted to scientists on Earth, and exciting discoveries based on the last bits of data are yet to come, NASA said.

“When we started conceiving this mission 35 years ago, we didn’t know of a single planet outside our solar system,” said the Kepler mission’s founding principal investigator, William Borucki, now retired. “Now that we know planets are everywhere, Kepler has set us on a new course that’s full of promise for future generations to explore our galaxy.”

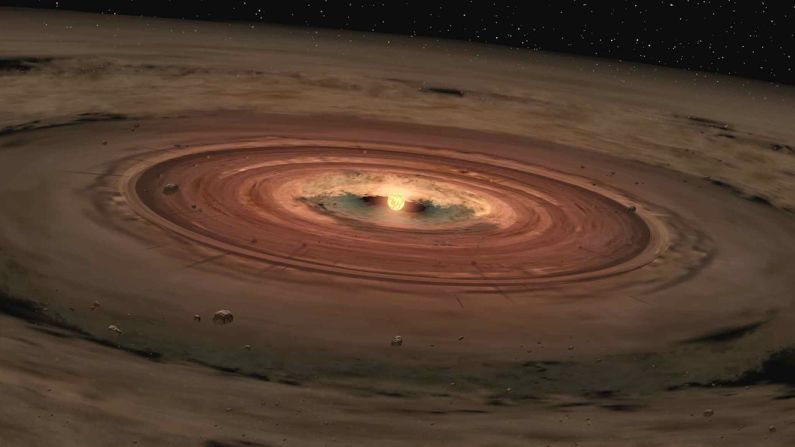

After launching in 2009, Kepler stared at the same spot in the sky for four years. The data revealed that planets are plentiful and diverse, planetary systems themselves are diverse, and small, rocky planets similar to Earth within the habitable zone of their stars are common, said Jessie Dotson, Kepler project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

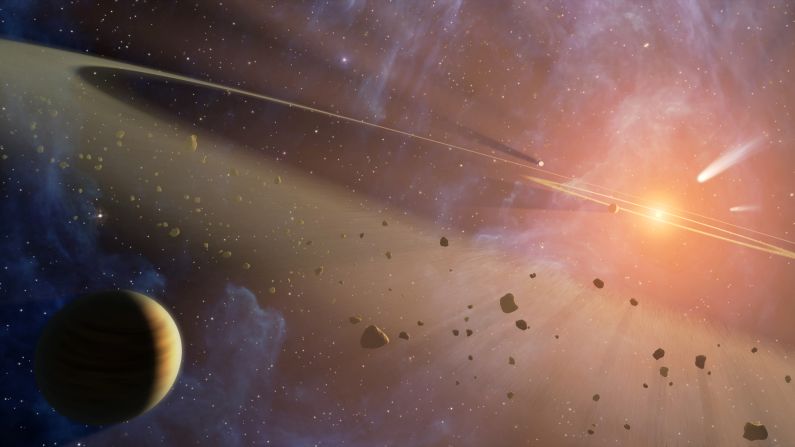

Four years into the mission, the main goals had been met, but mechanical failures put a sudden end to future observations. The engineers essentially rebooted the mission, devising a way to allow Kepler to survey new parts of the sky every few months. The new mission, studying near and bright stars, was dubbed K2.

K2 lasted as long as the first mission, allowing Kepler to survey more than 500,000 stars total.

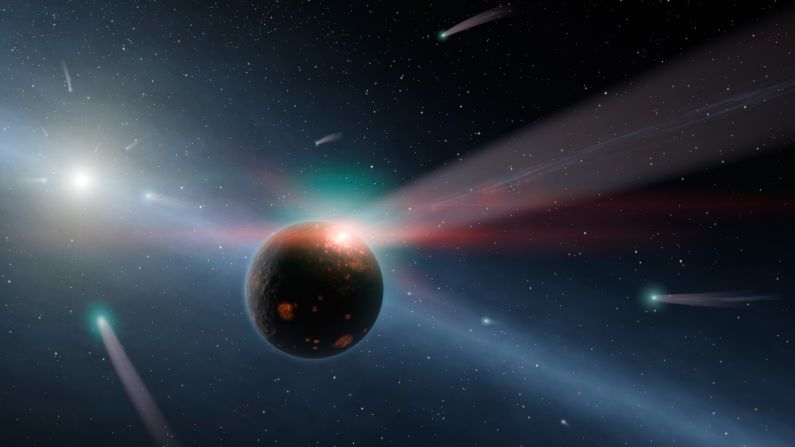

Kepler made incredible discoveries, revealing that there are more planets than stars in our galaxy. Kepler watched the very beginning of exploding stars, or supernovae, to gain unprecedented insight about stars and witnessed the death of a solar system.

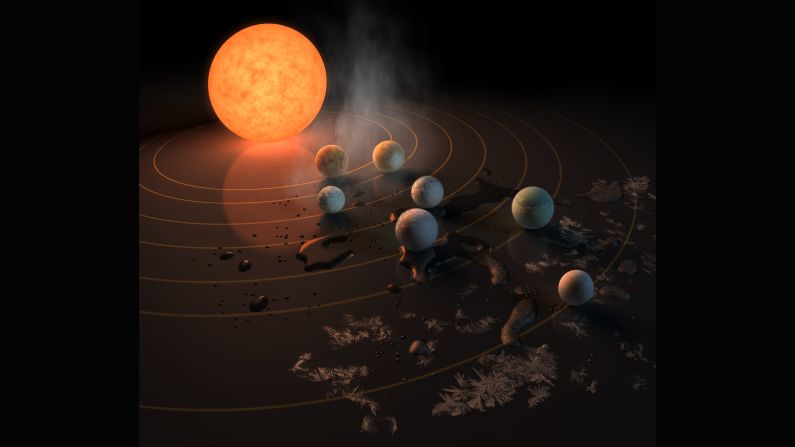

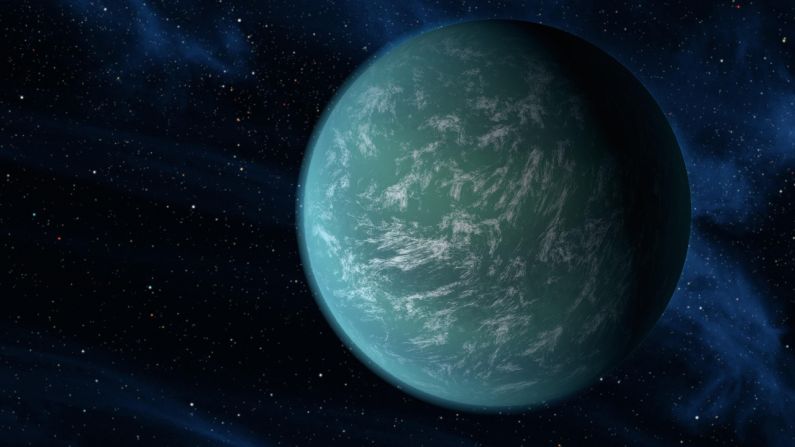

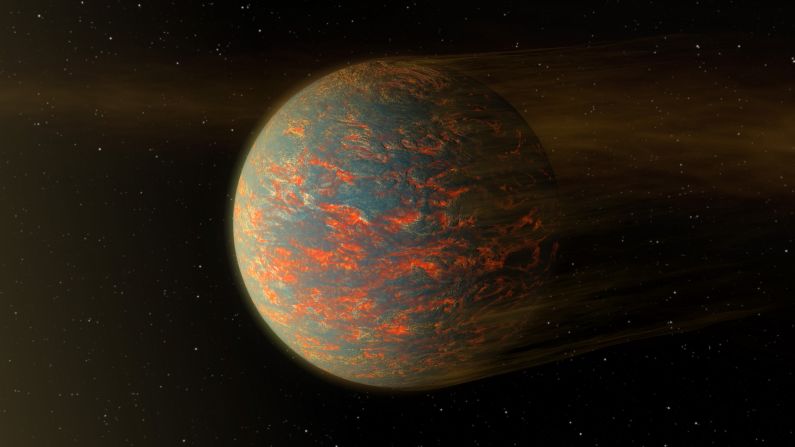

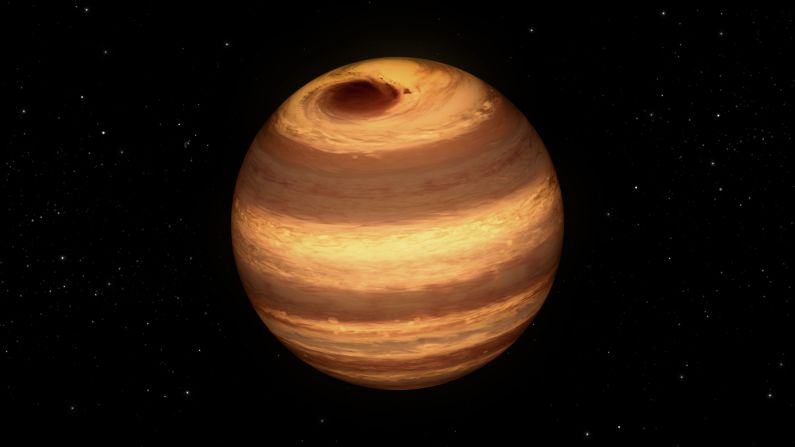

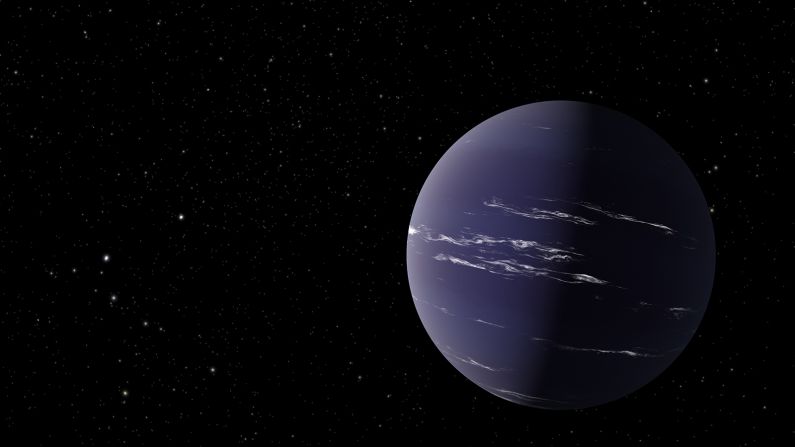

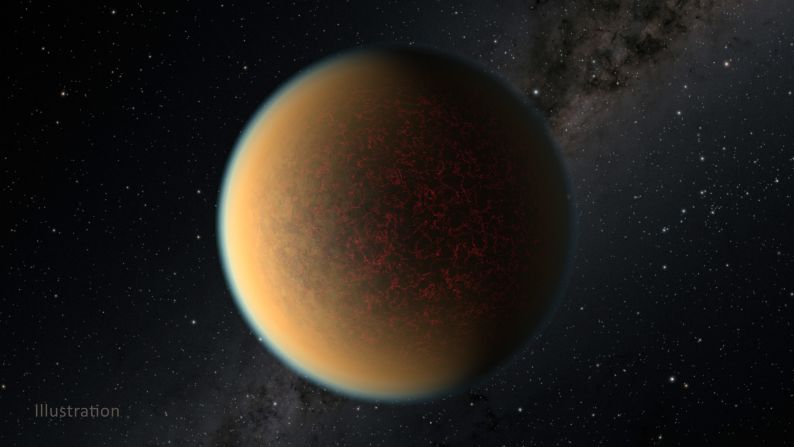

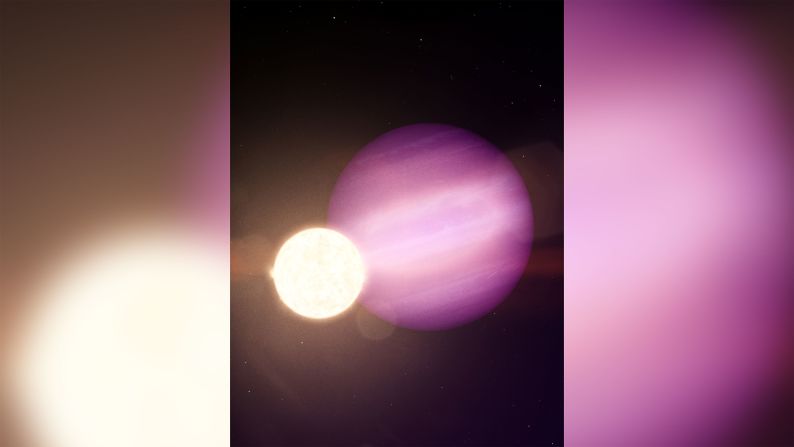

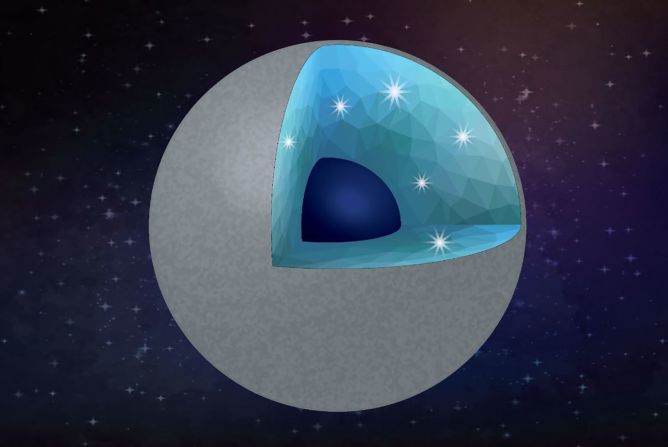

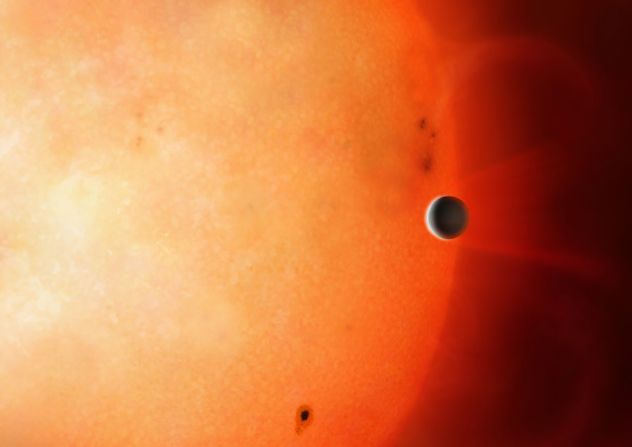

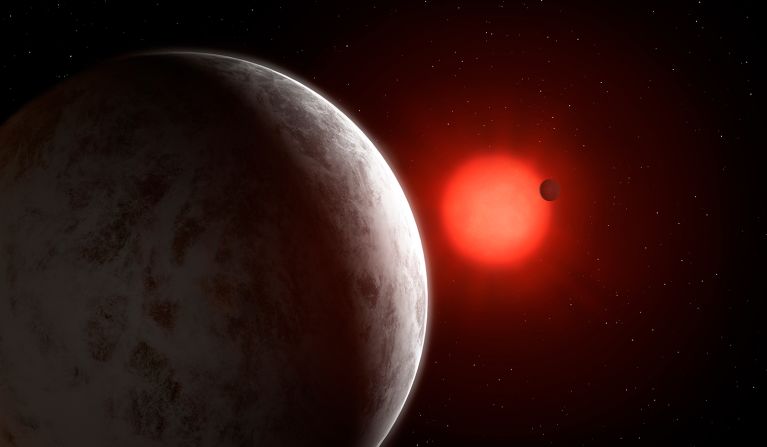

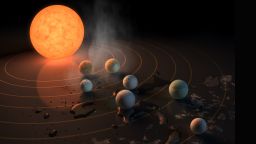

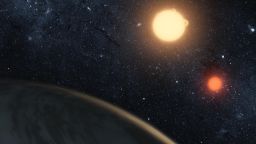

Astronomers were dazzled by the planets it found, including Kepler-22b, probably a water world between the size of Earth and Neptune. It found inferno-like gas giants, rocky planets, planets orbiting binary stars, Earth-size planets, planets in the habitable zone capable of supporting liquid water on the surface, planets twice the size of Earth, the strangely flickering Tabby’s Star, new details about the TRAPPIST-1 planets and, in December, an eight-planet system.

And those discoveries have helped shape future missions. TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, launched in April and is the newest planet hunter for NASA. It began science operations in late July, as Kepler was waning, and is looking for planets orbiting 200,000 of the brightest nearby stars to Earth.

Kepler hands off the baton to TESS now, NASA said. The first data from TESS is already being sent to Earth and analyzed.

Later, these planets – and those found by Kepler – can be studied by the James Webb Space Telescope, which will be able to look closer at the atmospheres and possibly determine their habitability.

Kepler was able to detect light from stars, but NASA is also studying plans for space observatories that are capable of detecting light from planets. This light would allow astronomers to take the spectrum of a planet and look for signs of habitability – and life.

“That’s the path Kepler has put us on,” said Paul Hertz, astrophysics division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Dotson noted, “We know the spacecraft’s retirement isn’t the end of Kepler’s discoveries. I’m excited about the diverse discoveries that are yet to come from our data and how future missions will build upon Kepler’s results.”