Story highlights

The operation took place last year, when the girl was 13 months old

"We had to choose between the death of the child and accepting an infected organ to save her," doctor says

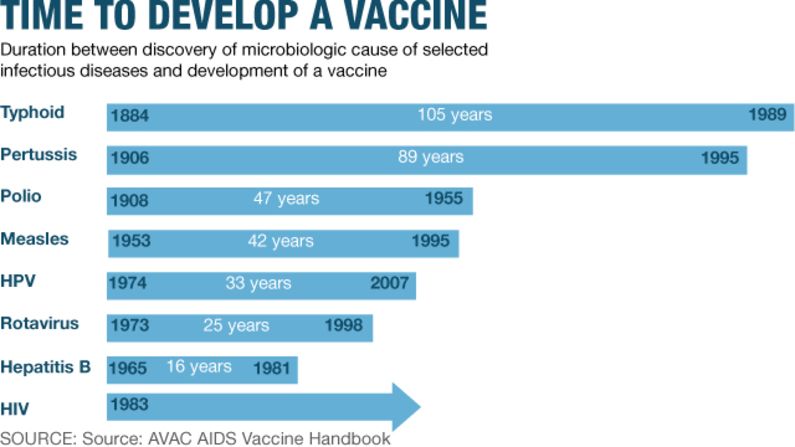

A liver transplant from an HIV-positive woman to her uninfected baby in South Africa has the potential to widen the country’s organ donor pool, experts say.

Doctors in the Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre transplant unit in Johannesburg announced last week that they had performed a liver transplant from a living HIV-positive donor to an uninfected patient, the first in the world.

The operation on the woman and her daughter with end-stage liver disease took place last year, when the girl was 13 months old.

Initially, two potential donors were determined to be unsuitable, and the mother, who doctors say will remain anonymous due to her HIV status, pleaded to be allowed to donate her liver but was denied.

Although people with HIV can donate organs in South Africa, they are not considered as potential donors in the hospital’s transplant program, in order to reduce the risk of transmission, said Jean Botha, the program’s director.

As the baby’s condition continued to deteriorate after three months on the organ waiting list, doctors said, they had to consider the mother’s desperate pleas.

Ethical decision

“We were faced with a tough decision,” said Botha, the lead surgeon on the case.

“We had to choose between the death of the child and accepting an infected organ to save her. The mother kept pushing and almost challenged us that we were possibly discriminating against her. Knowing HIV individuals live healthy lives, we had to take the opportunity,” he added.

Dr. Harriet Etheredge, a medical bioethicist who worked on the case, said the team also weighed the ethical implications.

“We were also faced with the risk to this child, having a child who was too young to tell us if they were willing to assume that risk,” Etheredge said, adding that investigation is ongoing to determine the girl’s HIV status.

The mother was monitored to ensure that her CD4 count was at acceptable levels. Her HIV viral load had been suppressed for six months before donation, and only part of her liver was used for the operation.

The baby was given three antiretroviral drugs the night before the procedure to prevent HIV transmission. An anti-inflammatory was administered during the operation.

Both mother and child are doing well and the baby remains HIV-negative, the doctors say, but they will continue to follow up with them.

“The testing on the baby has come up with some interesting results too, we cannot present it at the moment,” Botha said.

‘Unique case’

Organ transplants have previously been performed between HIV-positive patients.

Doctors at John Hopkins University performed the first kidney and liver transplants on HIV-positive patients in 2016. The donor had been living with HIV for 30 years, and the recipient had had the virus for 25 years.

South Africa has also had success in transplants between people with HIV.

But two things have made this case unique, doctors said: It is the first liver donation from a living HIV-positive donor in the country; donors in previous cases were deceased. It is also the first liver transplant from an infected donor to an HIV-negative recipient, with an intention to reduce transmission in the recipient.

“This is the ?rst such intentional liver transplant of its kind in the world,” the doctors said this month in the journal AIDS.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

The study demonstrates that living HIV-positive patients can safely donate organs, said Paul Mee, assistant professor of epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, while adding that the risk of recipients becoming infected cannot currently be ruled out.

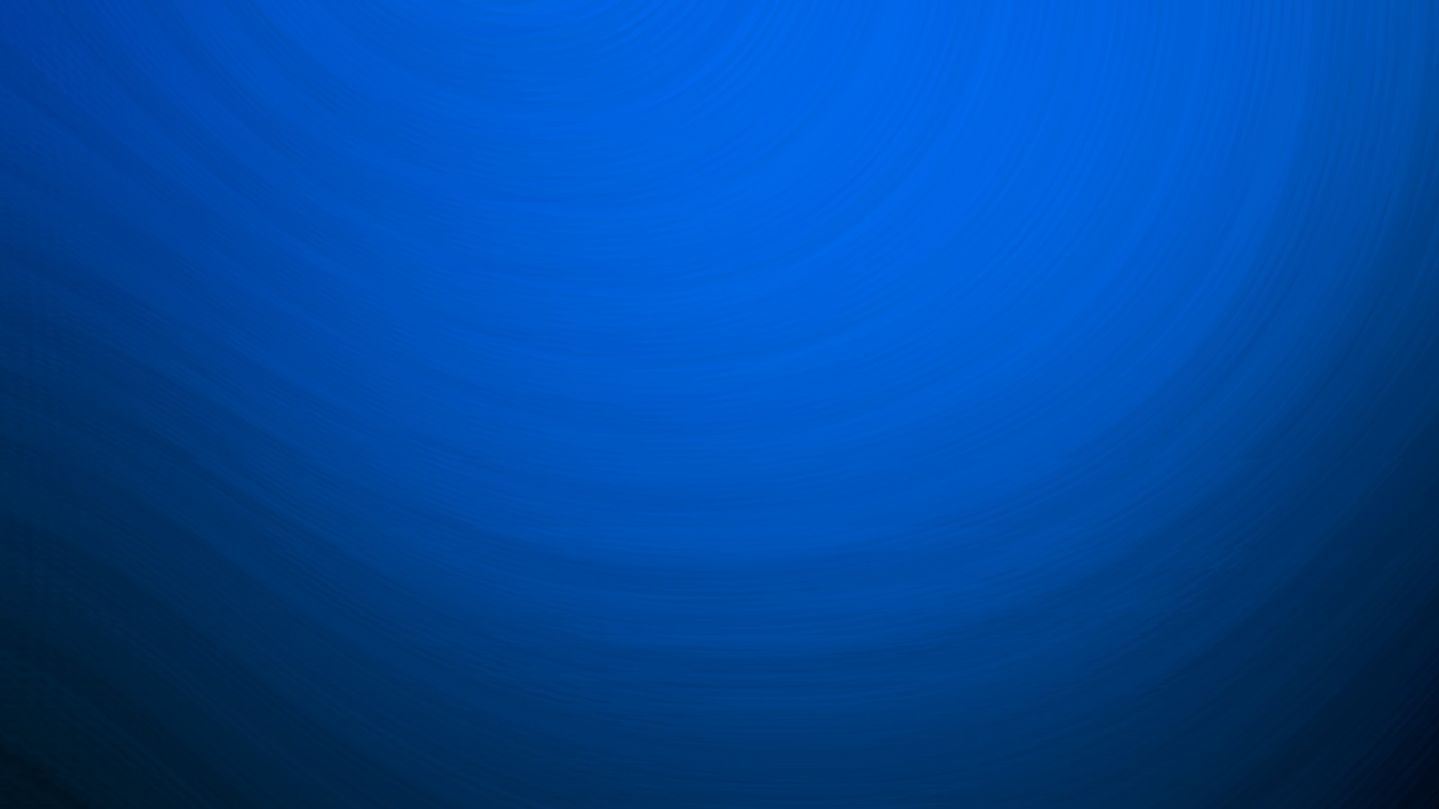

Adding HIV patients to the donor pool helps countries facing a shortage of suitable donors and offers South Africa, with its high HIV burden, more opportunity to offer transplant services to save more lives, Mee said.

“The shortage of suitable organ donors for those in need of a transplant is a major problem throughout the world. This problem is made much worse in countries such as South Africa with high rates of HIV, where infected individuals would normally be considered ineligible as organ donors due to the risk of infection for the recipient,” Mee said.

More than 4,000 people in South Africa are on the waiting list for organ and tissue transplant, according to Organ Donor Foundation of South Africa.

About 7 million South Africans are HIV-positive – 13.1% of the population – according to the country’s national statistical service.

“We face dire organ shortage, and this has created an imperative for us to look at alternatives to get our patients transplanted,” Botha said.