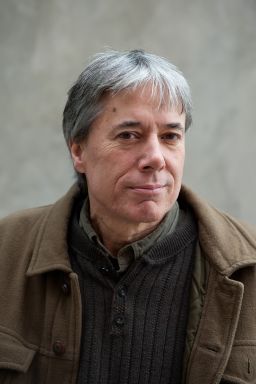

Editor’s Note: Chuck Collins is author of “Born on Third Base: A One Percenter Makes the Case for Tackling Inequality, Bringing Wealth Home and Committing to the Common Good.” He directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he co-edits Inequality.org. The views expressed here are solely his. View more opinion articles on CNN.

Why do public figures who are clearly “born on third base” insist they hit their own triple?

Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh claims he didn’t get any help getting into Yale after graduating from Georgetown Prep. “I have no connections there,” he said last week in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee. “I got there by busting my tail.” At Yale, however, Kavanaugh would be considered a legacy admission. His grandfather, Edward Everett Kavanaugh, attended.

Donald Trump boasts that he is a self-made billionaire who received no family help except for a $1 million loan from his father that he paid back with interest. But a sweeping investigative report by The New York Times estimates that Trump received at least $413 million, in today’s dollars, from his father’s real estate business. Yet Trump holds tightly to his personal bootstrap story.

No doubt both Kavanaugh and Trump have personal characteristics that helped them to advance in life. They may have “busted their tails,” as many low-wage workers also do. Hard work, creativity, and entrepreneurship should be celebrated and rewarded. But to deny the transformative role of family wealth and connections in future success is to pretend that there is no such thing as advantage.

I was born on third base. I attended a boy’s private school like Georgetown Prep, where the encouraging school motto was “Aim High.” I received a debt-free college education, no small head start in today’s economy, thanks to an education trust fund set up by my parents. And when I went to purchase a home in an expensive real estate market, I tapped into the “parental down payment assistance” program.

I’m the beneficiary of four decades of intergenerational advantage flowing up until the present. This includes access to tutors and health care, early enrichment experiences such as travel and summer camps, social networks, and unpaid internships in my fields of study. On top of being white, Protestant, and male, I was raised to have a sense of agency in the world. I’ve worked very hard at different stages of my life, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have a significant wind at my back.

To deny the role of family help fuels our larger cultural mythology around meritocracy and deservedness. If we believe that everyone is where they deserve to be, then there is no need to reduce structural inequalities and unequal opportunity. If everyone is where they deserve to be, why should anyone be troubled about decades of stagnant wages or a persistent racial wealth divide?

The United States is not yet a country with a hereditary aristocracy of wealth and power. But unless we address the persistent inequalities around us, we are drifting in that direction. If your advanced station in life was due to family connections, wealth, or advantage, then you are morally obliged to create a level playing field that gives others similar opportunities.

Nothing diminishes a public figure when they tell the truth about their struggles and advantages, and yet such honesty is rare. But as white men who won the lottery at birth, people like Trump, Kavanaugh and me shouldn’t pretend we were born in a state of nature and raised by wolves, rising to our station in life only through our own effort, gumption, and grace.

The problematic side of the self-made boast is the denial that other people face barriers, obstacles, and racial and class discrimination. After all, if I can rise through the ranks on my own pluck, they seem to say, so should you.

The new physics of inequality is compounding advantages for the haves and accelerating disadvantage for the have-nots. Thanks to what sociologists call the “intergenerational transmission of advantage,” family wealth and help play an oversized role in sorting out the economic prospects for the next generation.

But if I believe that success is based entirely on personal grit, then why should I pay taxes so that someone else can have a comparable head start to mine – with early childhood education, access to quality health care and mental health services, and low-cost higher education?

Good societies make taxpayer-funded investments in education, health care, and institutions of opportunity. America isn’t there yet. One way we get there is by telling true stories of how advantage works.