Editor’s Note: This story originally published August 9, 2018.

Adrienne Bennett has been breaking through glass ceilings for decades. But when people call her a pioneer for women in the nation’s plumbing industry she dismisses the praise.

“I tell them I’m no different than you,” she says.

But she is.

At the age of 30, while surrounded by men, Bennett became the first black female master plumber in the United States. Now, 30 years later, she is CEO of herown contracting company, Detroit-based Benkari LLC.

Bennett, who runs Benkari with her son A.K. Bennett, launched the commercial plumbing and water conservation company in 2008 when she felt she had hit the pinnacle of her career.

“I’ve been a journeyman plumber, a master plumber, project manager, plumbing inspector and code enforcement officer for the city of Detroit for a decade. There was no place left to go but become an independent contractor,” she says. “It was the final frontier.”

The fourth of eight siblings, Bennett credits her parochial school education for her discipline and work ethic. “I was taught as a young child that you finish what you start and you do a job well,” she says.

She was drawn to math and science and would go to hobby stores to buy aircraft models. “I loved putting together the Apollo spacecraft module,” says Bennett.

Her interest in the way things worked spurred her to apply for an entry-level training program with an engineering firm in Detroit. The program was a pathway into Lawrence Technology University, where she hoped to study mechanical engineering.

But a racially charged encounter with someone who worked at the firm shocked her so much that she left the program within a year and never attended college.

“I was young, naive. I had never been called something like that before. I was blindsided,” she says.

Her mother helped her through it. “I cried a lot, but she told me to take it as a life lesson and continue to move forward,” Bennett recalls.

For a few years she bounced around doing odd jobs, including work as an advocate for people on public assistance programs.

But then, at a 1976 election rally for Jimmy Carter, Bennett had a chance meeting that would change the direction of her life.

Gus Dowels, a recruiter from the Mechanical Contractors Association of Detroit, approached Bennett and asked her “How would you like to make $50,000 a year?” “I asked him, ‘Is it legal work?’,” recalls Bennett.

Dowels was working for a federally-sponsored apprenticeship program for skilled trades and he was looking to recruit minority women, she says.

Soon Bennett,who was 22 at the time, was taking the test for admission into the five-year apprenticeship program with the Plumbers’ Union, Local 98.

Throughout her training, Bennett was surrounded by men, bothin the classroom and in the field.

“It was dirty work. It was rough and physically demanding. It paid $5 an hour with a 50-cent raise every six months,” she said.

As she started to break through each barrier, successfully passing exams and earning praise from instructors, Bennett met backlash, hostility and bullying from her male peers.

“I always wore a very heavy toolbelt around my waist. I did this for protection because men would try to grab at me inappropriately,” she says. “Many times, I was the only woman with as many as 100 men on a construction site.”

One time the bullying was so intolerable that Bennett recalled driving in a fog back to the union hall and breaking down emotionally. But she pulled herself together and when she completed the program, she became the first women in the state to have successfully done so.

“I was not going to let myself or anyone else down,” she says.

Once Bennett had logged the required 4,000 hours of experience she needed to qualify for the master plumber exam, she took that test and received her state license. She had passed yet another milestone: Not only did she become the first black female master plumber in the state of Michigan – but also in the United States.

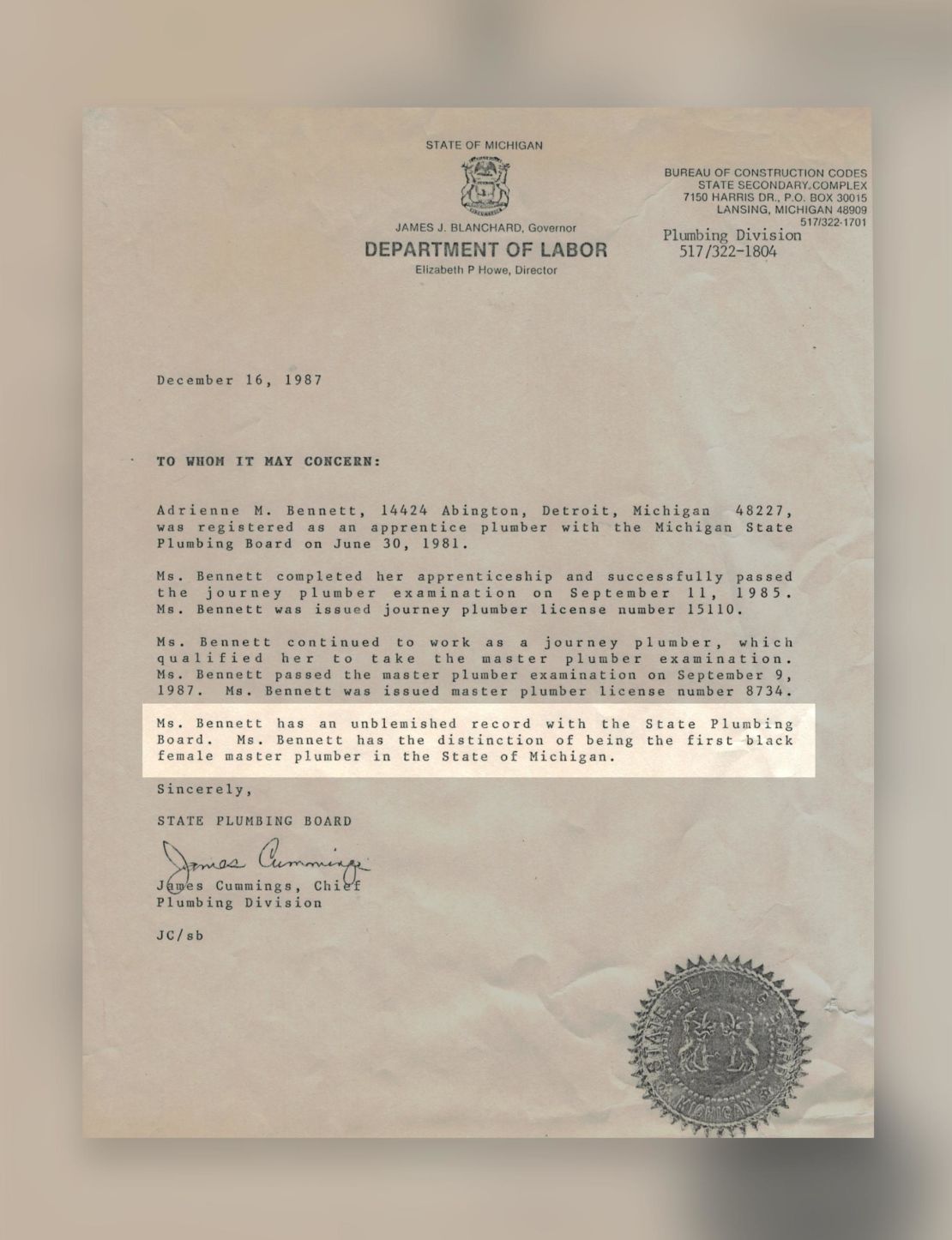

Michigan’s labor department recognized this distinction with a letter, noting her “unblemished record,” with the state plumbing board.

“I’m honest, hardworking and I don’t let anyone get in my way and cheat me out of my dream,” she says.

Bennett’s path hasn’t been without challenges, however. In 1995, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which forced her to finally take a break.

“I was in no shape to do anything for a long time,” she said.

But when she was ready, she launched Benkari.

Today, her business is involved in the effort to rebuild the city she has lived in since she was nine years old.

As Detroit recovers from its financial crisis, there’s been plenty of new construction and renovation work. And Benkari is profitable and landing some big contracts, including work for the Little Caesars Arena and the Anthony Wayne Housing Development.

Bennett’s son and partner, A.K., says he expects revenue at the company to triple this year as a result.

Now 61, Bennett is continuing to forge her own path in a male-dominated industry. She is also helping shape the next generation of skilled tradesmen and women by sitting on the advisory board for Lawrence Tech.

“I feel I am a survivor. We have to dig down and find our fighting spirit. It’s important to know that we all have it,” she says.