Editor’s Note: Jane Merrick is a British political journalist and former political editor of the Independent on Sunday newspaper. The opinions expressed in this commentary are hers.

There are very few people in the world who will know what Christine Blasey Ford went through in her testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday. Perhaps the only person who could possibly know is Anita Hill, who was made to endure the same process when she testified against Justice Clarence Thomas 27 years ago.

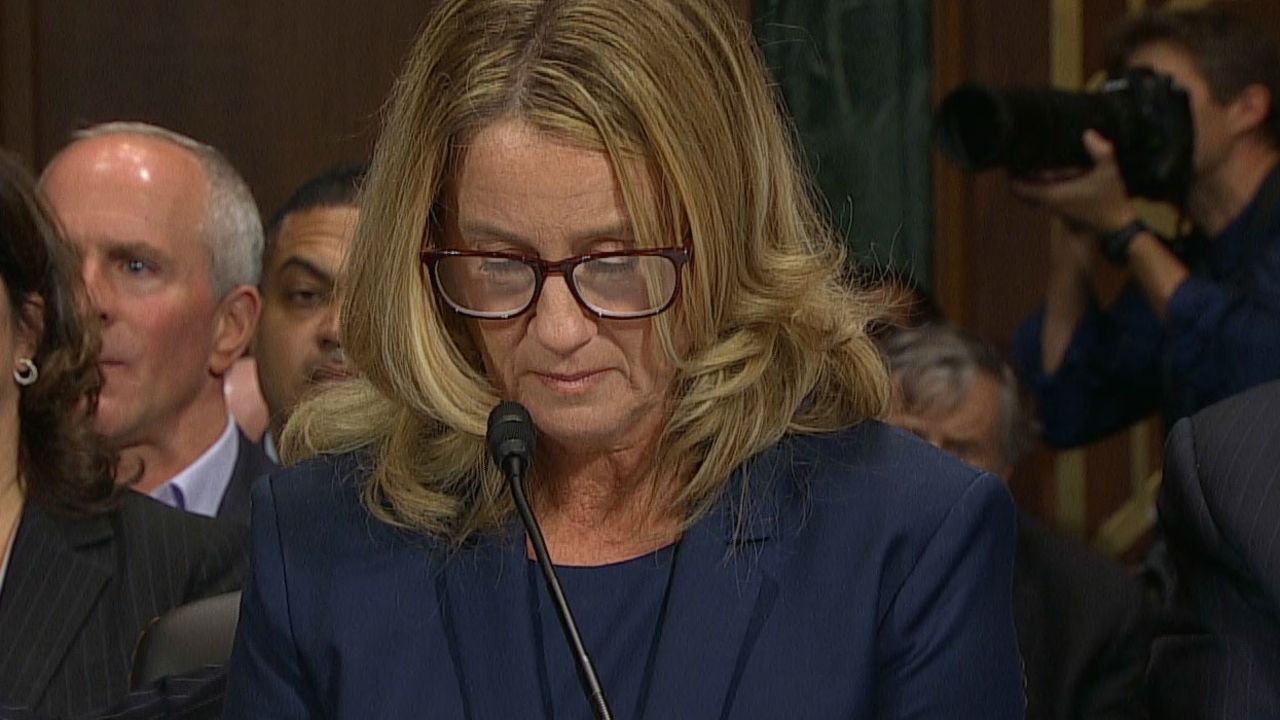

Under the glare of a spotlight and facing a sea of male faces, Ford revealed she was “terrified” at having to recount her allegation of sexual assault by Brett Kavanaugh, but she nevertheless did so because it was, in her words, her “civic duty.” It felt like a trial.

Her terror at being put through this – against her wishes, and after living with the original trauma of the assault – is unimaginable. But perhaps, to give a scale of her terror – and, in turn, her outstanding bravery – I can say how it feels to accuse a powerful man of sexual harassment, even under the cloak of anonymity.

Of course, our two cases are not comparable – both in the original incident and the subsequent media coverage.

Last November, I contacted British Prime Minister Theresa May’s office to report then-defense secretary Michael Fallon for sexual harassment. He had lunged at me, trying to kiss me, in a quiet corner of the Houses of Parliament back in 2003 when I was a young political reporter.

I had said nothing at the time because I feared recrimination from his allies in the Conservative Party. When I reported him last year, as the #MeToo movement swept through Westminster, I did so because I was aware of other, more recent, allegations against him. Historic allegations were being trivialized and dismissed by his allies. I reported him because I felt it was my duty to do so.

Crucially, I was allowed to report this anonymously. I sent a text message to the Prime Minister’s chief of staff, and he called me back straight away. I went through what had happened with the original incident, and how I had felt.

As I spoke down the phone, I was trembling with fear – 14 years on. Not because of the memory of the harassment, but the knowledge that I was accusing a Cabinet minister of sexual misconduct and reporting this to the Prime Minister.

To nail a lie that was hurled at me and so many other accusers during #MeToo: coming forward with an allegation of sexual harassment is not something an individual does lightly, or makes up. It’s not “jumping on a bandwagon.”

It is serious, onerous and somber. And when it is to demand that a powerful individual is held to account for his past behavior, it comes with an extra layer of fear. What if that person uses all the power at his disposal to retaliate? What if he denies it and tries to take legal action? What if the press comes after me?

The only answer is that the most powerful weapon a woman who has been sexually harassed has is the truth – and that it is able to be told.

In that phone call with the PM’s office, I fought back tears – out of relief that I had finally, after many years, reported what had happened and for the women younger than me who I wanted to protect. But there was a third reason, which seems bizarre and wrong: even though there was no guilt on my part over what happened, I felt some guilt that I knew I was likely about to bring down a powerful man’s career.

That feeling should not have been there, but it was, intrusively. I had agonized for days over whether to report Fallon. We shouldn’t feel the anguish, or the guilt, but women are often conditioned into bearing some responsibility for what happens to the men who harass them.

During that phone call, I received an apology on behalf of the Conservative Party. I was also assured my identity would be kept secret. When Fallon resigned, less than two hours later, I didn’t feel triumphant, only empowered, like I had taken back control.

A few days later, when I decided to reveal my identity, it was on my terms, in a newspaper article. Fallon had resigned. He didn’t deny what he did to me, nor the other past behavior.

For Kate Maltby, my journalist colleague who came forward to accuse another Cabinet minister, Damian Green, of sexual harassment, it went very differently. He denied it and Kate was subjected to character assassination in the press and a government inquiry. In the end, that inquiry found Kate’s account plausible and Green resigned.

I was, I suppose, fortunate that Fallon went so quickly and quietly. When I contacted Downing Street that day, I had no idea he would. My fear, however, was tempered by the protection of my anonymity. There was no grilling by high-ranking politicians, no glare of a spotlight, no worldwide audience. My experience is a tiny fraction of what Blasey Ford has endured, and so my fear that day at accusing a powerful man of sexual harassment must be magnified 1,000 times over for her.