Editor’s Note: Noah Berlatsky is the author of “Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.” The views expressed here are solely the author’s. View more opinion articles on CNN.

The recent accusations of attempted sexual assault against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh have led to an unusually naked demonstration of how male solidarity works, and for whom. Many conservatives who support Kavanaugh have come forward to argue that men are supposed to see themselves in Kavanaugh, and that men are supposed to share the same interests as Kavanaugh. The demand for male solidarity is a deliberate effort to make men forget that many of them have more in common with victims than with the powerful.

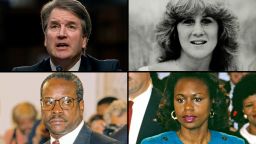

This week Christine Blasey Ford, a professor of clinical psychology at Palo Alto University, publicly accused Kavanaugh of assaulting her in 1982, when he was 17 and she was 15.

The reaction from some conservatives was swift – and appealed directly to male fears and male interests. A lawyer close to the White House, speaking anonymously to Politico, said that the nomination would not be withdrawn because “If somebody can be brought down by accusations like this, then you, me, every man certainly should be worried. We can all be accused of something.” Ari Fleischer, the former White House press secretary to George W. Bush, asked on Fox whether committing sexual assault in high school should “deny us chances later in life.” Conservative blogger and radio host Erick W. Erickson declared on Twitter that “If the GOP does not stand up to this character assassination attempt on Kavanaugh, every judicial nominee moving forward is going to suffer last minute sexual assault allegations” – as if sexual assault allegations are all simply some kind of plot against our boys.

Tom Nichols, a conservative professor at the US Naval War College and author of “The Death of Expertise,” initially sided with Kavanaugh — and then, reconsidered. As he perceptively explained on Twitter: “Listen, I’m a middle-aged man seeing a middle-aged man get nuked w/accusations from high school. It put me in a defensive crouch.”

Philosopher Kate Manne has a name for that defensive crouch; it’s called “himpathy.” Himpathy is the opposite of misogyny, Manne writes in her book “Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny.” Misogyny means that people react negatively or dismissively towards women; himpathy means that they react positively or empathetically towards men. Men sympathize with alleged abusers because himpathy puts them in the shoes of the victimizers, rather than the victims.

“Himpathy primarily concerns cases where powerful and privileged men garner unduly sympathetic attention over their less privileged female victims,” Manne told me by email. “It plays out in a variety of ways: denying her story altogether, trying to undermine her credibility, calling her a liar or hysterical, or implying it somehow wasn’t a big deal because it didn’t happen yesterday.” Another common theme is “he was a ‘good guy’ even back then, who was smart, athletic or popular.”

The arguments are so various because they aren’t based on logic but on emotional identification. Apologists, Manne says, will do “anything to shift the blame from where it belongs,” and anything to prevent women “from being the proper object of moral concern and sympathy.”

The appeal to himpathy assumes that any man benefits when he identifies with other men. But are men’s interests really best served by identifying with and promoting the interests of those accused of sexual abuse or misconduct? In 2018, the government estimated that over their lifetime 2% of men will be raped and 23% of men will experience some other form of sexual violence. This is far less than the 44% of women who experience sexual violence, but it is still very high.

False rape charges in contrast make up only about 2% to 8% of total rape reports, according to the best current research. A quarter of men can expect to experience sexual violence; far fewer men are going to be the target of false rape or sexual harassment allegations. Why in cases of sexual assault should men automatically identify with the accused, when statistically they have a one in four chance during their lifetimes of being the one assaulted?

As a parent with a son who is interested in acting, the #MeToo movement has made me very aware of the dangers men and boys can face. At least one of the young actors Kevin Spacey reportedly harassed, Adam Rapp, was my son’s age at the time of the incident. And Terry Crews’ experience shows that men of any age can be assaulted in Hollywood. The current #MeToo movement has brought to light numerous instances in which men and boys have been harassed and abused by men and women.

Yet, these male victims are often systematically erased in discussions of harassment and abuse in order to paint all men as sharing a common experience, and common interests, with abusers and rapists. Men as a group are supposed to benefit when certain men are granted impunity or given absolution for a “comeback,” even though it should be obvious that many men do not benefit when you tell them they are supposed to sympathize with the people who assaulted and abused them.

Manne notes that himpathy is not distributed equally to all men. It is directed especially, she writes, to “men who are white, nondisabled, and otherwise privileged ‘golden boys.’” Himpathy leads everyone to see powerful men as important, worthwhile, and sympathetic, and to treat women with suspicion and doubt. That’s why Republican Susan Collins, in Democratic-leaning Maine, has been the focus of Democratic anger and misogynist abuse for potentially supporting Kavanaugh, while Republican Cory Gardner in Democratic-leaning Colorado, has been almost completely ignored. In a misogynist culture, even women may find it easier in some cases to see the perspective of men. And as for men, they are encouraged to identify with the manliness of powerful men more thoroughly than they identify with their own masculinity, or than they identify with themselves.

In 2016, 53% of men voted for a billionaire scam artist for president; many of them did so because he offered them the opportunity to vicariously cheer for patriarchy, even as he gutted their health care. Himpathy makes men support the powerful men who abuse them. But what if, instead, when women like Ford come forward, men said, not, “that could be my daughter,” but, “that could be me”?

Because the truth is it could be me, or you, or any man. Powerful perpetrators of sexual violence target women especially, but not exclusively. When men acknowledge our own potential vulnerability, we open a way to solidarity with, and justice for, people of every gender.