Before the events of August 11 and 12, 2017, Charlottesville was, for those who knew of it at all, a college town or a weekend getaway from Washington, DC. Or, for the history buffs among us, the home of our third president. After those events – the torch-wielding march at the University of Virginia, the “Unite the Right” rally and the violence and injuries it wrought, and of course the horrific murder of Heather Heyer – Charlottesville has been a national wound for many Americans, a symbol of violence at the heart of America’s relationship to race.

But for the more than 45,000 residents of Charlottesville and tens of thousands more who live nearby in Albemarle County, this town isn’t a symbol – and what happened to it on August 11 and 12 isn’t an abstraction. For them, Charlottesville is home, a place now marked by a trauma they walk near and live with daily – and respond to differently, each according to his or her own experience.

To mark the one-year anniversary of this tragedy, CNN Opinion reached out to a diverse group of residents and people directly affected by the events of August 11 and 12, 2017. Here, in their own words, women and men of many backgrounds, faiths, and ages answer the question: What were you doingi on August 11 and 12, 2017 and what have you done since? Where do you think America stands when it comes to issues of race and justice?

Susan Bro: My world was demolished

On August 11, I was a secretary and bookkeeper. I spent that Friday reviewing records from fiscal year 2017 in preparation for an audit. I already had a plan for the files I planned to pick up with on Monday. After supper, I sat down to work on a crochet baby sweater and blanket set for a friend.

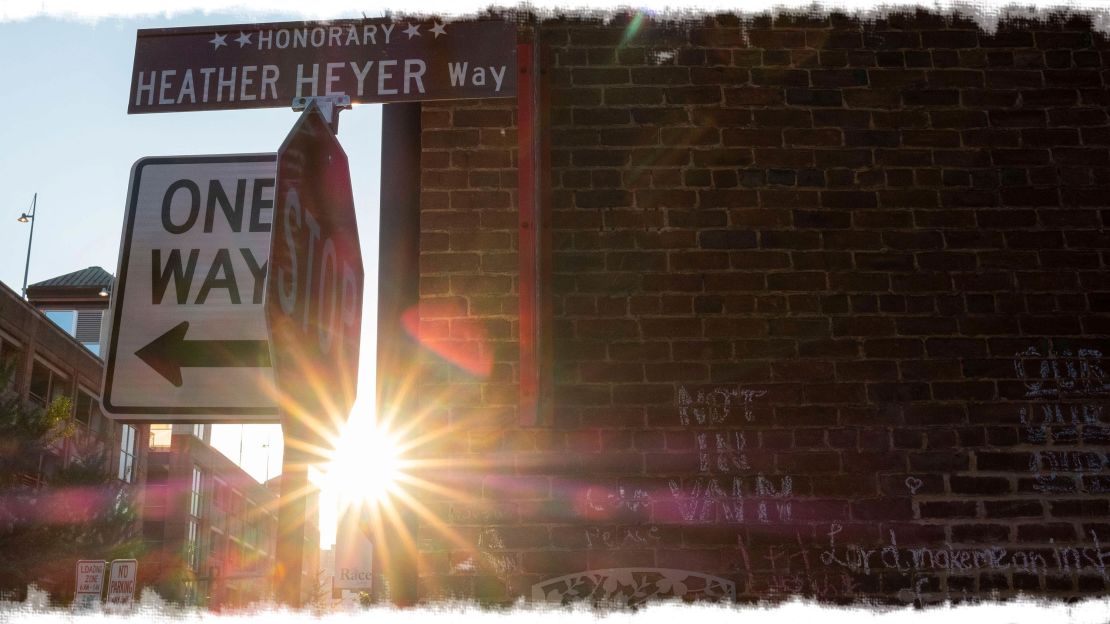

Twenty-four hours later, my world was demolished. A young man drove his car into a crowd of peaceful counter-protestors, wounding many and killing my daughter, Heather Heyer. She was gone in an unbelievably public murder, filmed by so many that day. Her death was shown over and over again on TV, but I didn’t even know details of her final moments, even what she was wearing. I cried all night long.

When the first knock on the door by members of the media came at 7 a.m. on August 13, I had a choice to make – turn inward from the grief, or maybe forgive her murder. Everyone would understand if I called for vengeance. But none of those felt truly from my heart. They were not sustainable and offered nothing of value. My decision was to respond with a call to action.

It made me so angry to have my daughter silenced that I determined I would speak for her instead.

Heather always had a passion for making sure everyone was treated fairly. Even as a child she often stood in defense when she saw a need to speak up for others. Not only would I speak, but I would also encourage others to speak up. In response to one voice lost, there would be hundreds more in her place. My work with the Heather Heyer Foundation is a means to that end.

The Foundation was formed to provide a legal and accountable structure for handling the donations pouring in the first weeks. The initial purpose was to provide scholarships for those individuals who were already positive, non-violent social activists and wanted to further their education to support continued activism.

We joined forces with The AIDS Health Care Foundation to have youth show how they were able to #StandAgainstHate. Winners received over a total of $8,000 in scholarships from AHF and $1,000 from us.

Those winners also expressed a strong desire for a youth empowerment program, which they named “Heyer Voices.” This program, which is in development now, will help young activists get hands-on training and support from adults on how to handle the details of developing a youth-chosen, positive, nonviolent campaign for justice.

We have also given three high school graduation scholarships from our fund at $1,000 each and are continuing to expand our programs to offer more scholarships in the future. Our focus is to support the education and training of the next generation of activists, advocates and allies.

Our country must take the time to root out the disease of hate. We should not hasten to “heal” without dealing with the underlying issues of hurt and mistrust and inequity. People of color have never been treated as if they matter in our country. When one group of us is marginalized, we all suffer for it. We must work together to clean the infection of hatred.

I hope that what I do will support that goal.

Susan Bro is the mother of Heather Heyer and the co-founder of the Heather Heyer Foundation. She will be on Anderson Cooper Full Circle live on Facebook at 6:25p ET Friday.

Wes Bellamy: We are on the path to clear water

My grandmother always told me that before getting to the clear and clean water, you have to go through the mud.

August 11 and 12, 2017 and the months thereafter have been muddy for my city of Charlottesville.

August 11 was supposed to be one of the happiest days of my life. I defended my dissertation at Virginia State University early that afternoon and officially became Dr. Wes Bellamy.

Unfortunately, there was no huge celebration. A cloud hung over my head as I knew that as soon as I finished the presentation, my city was about to be swamped by white supremacists who were intent on invoking terror. As the vice-mayor of the city, the only African-American on the city council at that time, and thus the target demographic that the majority of hate and vitriol was aimed at, I had to be present.

That weekend I sat in a church Friday night and saw the fear on hundreds of peoples’ faces as we sat trapped inside a church while white supremacists walked outside with tiki torches.

On Saturday morning I led a march and chanted in the middle of the street from First Baptist Church throughout the city to claim what was ours and defy the hate. I then watched as evil marched throughout our city. It was as if the KKK of old had been reincarnated, and sent back to simply invoke fear.

In the midst of all that hate, I also went to a righteous community back-to-school bash on August 12 led by young, black leaders. A conscious group of brothers and sisters were intent on not allowing white supremacists to define our city. They gave away 200 backpacks, free food, and created an atmosphere of safety and community in the midst of chaos.

My city will never be the same, but we will no longer quietly walk in the mud of white supremacy. We are on the path to clear water.

Wes Bellamy is the vice mayor of Charlottesville. In 2016, he called for the removal of a local statue of Robert E. Lee in the park, a move which the “Unite the Right” organizers were protesting.

Lisa Woolfork: The problem with politeness

Charlottesville is a city of illusions. Those for whom Charlottesville is the Happiest City in America rarely see beneath this fa?ade. As a black professor at the University of Virginia who also organizes with Black Lives Matter Charlottesville, I recognize the ways in which the city sanctions white supremacy through polishing its veneer of civility and politeness. I spent the weeks leading up to the white supremacist attacks (and the year since) being told directly by polite moderates that the KKK should be ignored and that I should stay home when white nationalists in our streets threaten my very existence.

Last year, Charlottesville granted permits for men in Nazi uniforms and Klan robes to march in our streets. Charlottesville failed to prevent and then failed to prosecute men using lit torches to attack undergraduate students. Charlottesville uses legal shields to preserve racist monuments. And when community members respond in grief and rage, as we did when we marched for DeAndre Harris and Corey Long, we are targeted with social pressure under the polite gaze of white moderates, with demands to simmer down and behave with “decorum,” a code word for complicity. They say they want peace and quiet, but they’ll settle for just quiet. Politeness and civility are the very actions that brought us here in the first place.

Thomas Jefferson’s nearby Monticello, epitomizing the politeness of Southern hospitality, enslaved 607 Black people during his lifetime. Generations lived and died in bondage at plantations known for their hospitality. The Lost Cause mythology, the ideological devotion in the 19th and into the 20th century to falsely portraying the Confederate cause as heroic, then used the veneer of politeness to obscure one of the greatest human rights atrocities of all time.

Yesterday’s “Lost Cause” is today’s “civility.” Politeness is political: those who urge tolerance in the face of racist violence weaponize civility. Just as institutions of liberal democracy are harnessed by white supremacists for their fascist agenda, so too are civic virtues such as politeness, decorum, and civility used by white moderates to conceal and enable fascist actions.

Dr. Lisa Woolfork is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Virginia and organizer with Black Lives Matter Charlottesville.

Andrew Griffin: Since Charlottesville, America has collectively taken steps backward on race

I watched alongside the rest of the nation in utter shock as the events of August 12 unfolded in the last place I could have possibly imagined. As the Communications Director for Tom Garrett, the member of Congress representing Charlottesville, I remember speaking to my boss that morning and was proud to see his swift and very public denunciation of the vitriol coming from these hate groups and subsequent efforts in the aftermath.

Since this tragic day, America has collectively taken steps backward in appropriately addressing race relations. Political partisanship has driven a wedge between families, races, and genders which has fast-tracked a loss of the elements that once made this country a model for all others to follow.

In some convoluted and misguided attempt to quick-fix our shortfalls, many have channeled their efforts into removing monuments and renaming schools, completely disregarding the potential to repeat mistakes of the past by pretending history never happened. This is why I think it’s imperative to emphasize the importance of not allowing our emotions to control the narrative. There is no doubt that this extreme minority of torch-wielding bigots represented the absolute worst our society has to offer. However, ignoring history only affords a larger platform for a handful of racists to spew their hate while doing nothing to actually address the issue of race relations in our nation.

America is ground zero for freedom of thought, religion, and opportunity. While we have had shameful moments in our history, we have overcome those moments and grown as a society. Let’s not take steps backwards by accepting hate on either side of the spectrum. The next generation of Americans depend on what happens next, and the world is watching.

Andrew Griffin is a former congressional candidate and student-athlete at Virginia Tech who is completing his Master’s in Strategic Public Relations at George Washington University while serving as deputy chief of staff and communications director for Rep. Tom Garrett (R-VA).

Alexis Gravely: I was a student reporter covering a national tragedy

I remember last August. 11 and 12, in segments. I remember chants of, “You will not replace us” booming in my ears as the torchlit march passed the building that houses the Cavalier Daily office. I remember being in front of Emancipation Park on Saturday, choking and gasping for breath through the chemicals that filled air (I still don’t know whether it was tear gas, pepper spray, or some horrible combination of the two). I remember receiving the notification on my phone, stunned, when our editor-in-chief texted us that a car had purposefully run into a crowd of counter-protesters downtown. I remember hugging a stranger at Heather Heyer’s vigil as we cried into each other’s shoulders, releasing a piece of the mountain of emotion the weekend had brought.

I’m often asked how things have changed since last August. On the surface, a lot has changed. Being on the university grounds and being in Charlottesville doesn’t feel the same, and in many ways, it isn’t the same. I’ve grown and shifted considerably as a person since last year. But fundamentally, I’m still doing what led me to being at Emancipation Park in the first place – writing and reporting. This is a time when lots of Americans are amplifying their voices on issues of race, protest, and justice. I’m inspired as a reporter to not only project and amplify those voices even further, but also to bring life to those who are unheard. Our country has a lot of progress to make, but I’m hopeful that up-and-coming journalists like me will continue to tell the stories that help us all find common ground.

Alexis Gravely is a student at the University of Virginia. She is the assistant managing editor of the Cavalier Daily and has been a fellow with The Nation and Anna Julia Cooper Center.

Nicole Hemmer: One question I always asked was: ‘Do you have hope?’

There’s a lot I remember about August 12. The sound of low-hovering helicopters. The choking taste of smoke and pepper spray. The echoing crack of clubs against a young man’s skull. A wail of terror. A street clogged with bodies and blood.

There are also things I don’t remember, a part of the day that trauma wiped away.

Yet I’m unlikely to forget the events of August 12, even as my memory of that day will never be whole. I provided on-the-ground coverage via social media of both the violence at the park and the car attack that killed Heather Heyer. In the days that followed, I wrote about my experiences and continued to speak to the media. After one interview, I sat in my car and cried. I was used to being asked about my scholarly work on conservatism and the alt-right. I wasn’t used to being a witness.

That tangling of personal experience and professional expertise felt messy and uncomfortable. And yet several months later, I realized that discomfort meant I had more to say.

Over the past four months, I’ve worked to create a podcast, A12, that explores what happened last summer. The episodes include the voices of more than 20 activists, witnesses, scholars, and city and university leaders. It moves from the events of what is locally known as the Summer of Hate into the deeper history of Charlottesville, the alt-right, and the challenges of policing and law that last summer revealed.

The interviews were often tough, because lots of folks were reliving trauma and talking about some of the darkest forces in our politics and history. So one question I always asked was: “Do you have hope?” Each time, I think I was asking as much for myself as for the podcast.

And every single person I asked said yes.

They said yes, I think, because while the world may have seen only violence in Charlottesville on August 11 and 12, they saw something more in the year since. Resistance. Resilience. And if that’s the story Charlottesville tells — not just tells, creates — in the aftermath of last summer, then their hope is very well-founded.

Nicole Hemmer is an assistant professor in presidential studies at the Miller Center at the University of Virginia and the author of “Messengers of the Right.” She hosts the history podcast “Past Present” and has just released the new podcast “A12.”

Brenda Brown-Grooms: We are still working together to keep the American Dream alive

I was at the sunrise service at First Baptist Church on Main at 6 a.m. on August 12, with Cornell West, Tracy Blackmon, Osagyefo Sekou and various groups soon to be deployed to our respective stations (mine to First United Methodist Church, a designated safe space, prayer fortress, first aid station, food and water replenishing). We prayed, sang, read Scripture, counseled with those coming in for respite. We were tear gassed (it wafted up from the park across the sidewalk), were locked down more times than I can now remember, and watched Heather Heyer being killled and others injured in real time, via livestream, while hearing a helicopter hovering over our heads.

A little more than a month before the July 2017 gathering of the KKK in Emancipation Park (in protest of the city’s approved plan to remove the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee) we all got word of this coming August gathering. Concerned citizens, rightly discerning this to be, above all, an issue of morality and not just policy, called on their faith leaders to lead Charlottesville’s response. Indeed, they were crystal clear: if you don’t lead, we won’t follow.

We mounted prayer vigils, monitored KKK/alt-right social media, tried to work with various police departments in this area, and quickly discovered that they were not listening to us, which later bespoke their unpreparedness for the situation.

After the July protest, those of us in the faith community realized the enormity of the coming situation and sought to prepare ourselves and our congregations as best we could. Our biggest hindrance was the intransigence of the city government, university administrators, and Charlottesville’s elite in convincing themselves that something like what did happen would never happen in beautiful, iconic, happy Charlottesville! THIS ISN’T WHO WE ARE!

However, beautiful Charlottesville has an ugly underbelly. If you have enough money, enough power, the right zip code, preferably no Jewish ancestry, and are not a person of color, you may well be able to position yourself, isolate yourself,so that none of what poor, powerless, native Charlottesvillians of color experience. I am an African American native of Charlottesville and a graduate of the University of Virginia. I remember and have always experienced the ugliness of this beautiful place.

To those who stubbornly thought it “couldn’t happen here,” I say: Are you insane? Of course this is Charlottesville. What planet do you live on? Yes, some Nazis and KKK and alt-righters came from out of town, but a lot more of them than you think live right here.

On August 11, I participated in a glorious worship service at St. Paul’s, across the street from the Rotunda at UVA, where the tiki torch gathering happened and Nazis cried, “Jews will not replace us.” I, along with about 500 people, was locked down in the church. I had a premonition that something would happen on Friday. They had to announce their presence some way.

Last summer crystallized for me, yet again, that America has yet to live out her creed (that all people are created equal, endowed by our Creator, with certain inalienable rights. That among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness). Everyone ever labeled a “minority” in this country knows America’s failure, its original sin. And yet, each generation, we hope and work for the American Dream. The original sin that infects our republic, our religious practices and citizenship in the world is white supremacy. We must admit it. Rout it out. Begin again. We must talk about who benefits and who does not. We must admit that our institutions are shot through with unfairness, injustice and death. We must hear and include the stories that have been and are still being suppressed in order to perpetuate a false, an incomplete narrative–leaving out Native Americans, Asian Americans, South Americans, African Americans, Immigrants, Refugees and those left without homelands and others in any of the myriad ways we humans know to “other.”

Since last year’s open summer of hate, I have found brothers and sisters of all races, creeds, faith or no faith traditions, who have been willing to sit together, talk together, argue together, cry together, think together, plan together, walk together, to keep the American Dream alive, one more generation. We are working together to raise up another generation to follow us, who will do the same. Shalom.

Brenda Brown-Grooms is a pastor with the New Beginnings Christian Community and part of the Charlottesville Clergy Collective (CCC), a group of clergy and laypeople dedicated to dialogue about the challenge of race relations in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. She is also part of and Congregate Cville, an activist organization which grew out of CCC.

Risa Goluboff: I found the resolve to keep asking MLK’s question, ‘Where do we go from here?’

After the violence and hatred of August 11-12, I cycled through a whole host of emotions: grief, revulsion, fear, anger. I eventually settled on resolve — resolve to render meaning out of tragedy, and to reignite progress to make the world, my hometown, and my university more just, equal, and inclusive places.

That resolve was put into motion when UVA President Teresa Sullivan asked me to lead the working group charged with the University’s response to the events. I had to say yes. It was not only that I wanted to help heal and empower the university that had been my professional home for fifteen years. It was also that, as a civil rights historian, I needed to understand whether this newly violent and visible form of bigotry was the last gasp of a backlash to a half century of civil rights progress or the beginning of a new upsurge against it. And I needed to do whatever I could to prevent it from becoming the latter.

I spent the better part of last year asking Martin Luther King, Jr’s pointed question: Where do we go from here? Beyond enhancing the future safety and security of our community, our working group had two overarching objectives. First, we recommitted to our values of diversity, humanity, equality, mutual respect, and honest and empathetic exchange across our many differences. Second, we asked how we could put our resources and expertise toward better understanding August’s events and their relationship to the wider world.

The concrete steps we took followed from those goals: expanding scholarships for students from diverse backgrounds; dedicating funds for new professorships to help understand, respond to, or prevent events like those of last August; reviewing how the University physically represents its history, including through public symbols and historical markers; and developing and supporting programming that helps people from diverse backgrounds communicate, learn, and work together. I am proud of what we have accomplished in answer to King’s question, even though more remains to be done.

When I reflect on the University’s response, I am especially heartened by the fact that so many students, staff, and faculty across our community took action. They stood up to hate, organized events, brought in speakers, held teach-ins, wrote op-eds, raised critical questions, and engaged in difficult conversations.

This overwhelming reaffirmation of our values, this simultaneous outpouring of support for one another and condemnation for white supremacy, reveals the big picture. It is this: the white supremacists took the spotlight for a day, but we have resolved to resist the hate they peddle forever. As I wonder what lies in store this year, I have no doubt that our resolve will endure. We will continue to work hard to transform the name of our hometown, “Charlottesville,” from a lament to a rallying cry.

Risa Goluboff is dean of the University of Virginia School of Law, a civil rights and constitutional law scholar, and a 15-year resident of Charlottesville. She is the author of “The Lost Promise of Civil Rights” and “Vagrant Nation.”

Emily Gorcenski: It didn’t surprise me that it happened in Charlottesville

The question I get most often these days is, “Did you ever think that this could happen in Charlottesville?” And I think it surprises people when I answer, “Yes, absolutely.”

Charlottesville imagines itself to be a happy, progressive college town. We have spent the past decade receiving accolades from lifestyle magazines whose target audience is wealthy and predominantly white. “Happiness is a place called Charlottesville,” said one such headline.

But the city has always had a dark past when it comes to race, and not everyone has been able to live happily in here. Of all the cities and counties in Virginia, it’s the one with the worst income inequality, according to a 2016 report from the Economic Policy Institute.

So no, it didn’t surprise me that the “badges and incidents of slavery” would once again rear their ugly heads in a town whose legacy includes the labor of Thomas Jefferson’s slaves.

Until we acknowledge that history, we will never move forward and never heal. Despite all the harassment and violence I have been subject to as an activist speaking out about these issues, I am in a way still very fortunate: I was able to leave to find peace. But no one should have to leave a place called “Happiness,” and the most vulnerable among us aren’t able to.

Emily Gorcenski is a data scientist and activist. She is a former resident of Charlottesville now based in Berlin.

Michele St. Julien: The day I moved to Charlottesville

I arrived in Charlottesville, VA, on August 12, the second day of the white nationalist rallies, to move into my new apartment and begin law school. I had traveled from New York with my family in two cars and one U-Haul truck. Charlottesville is the furthest south that I have ever lived, and I did not quite know what to expect.

I heard about the rallies first through friends from back home who frantically texted me the breaking news headlines. I came that day as a Black, queer woman, the daughter of Haitian immigrants, and a first-generation law student. I easily felt like the target of the hatred brewing just around the corner from a place I would call home. My family and I were moved to witness the rally with our own eyes and therefore ventured to the downtown mall area. I remember seeing men carrying large rifles, confederate flags, and clusters of what looked to be Klansmen. As the interactions between the rally participants and protesters seemed to be growing more tense, we decided to leave and head back to my apartment. I was home for about an hour when I heard the news about the tragic event that took Heather Heyer’s life. That moment still sits with me in a very uneasy way and I continue to think about her bravery and pray that her family finds peace.

While arriving to Charlottesville that day felt like an esoteric experience, somehow, I felt that my journey over the years had led me to that very moment. My own identity gives me a passion to insert often unheard groups and interests into the proverbial rooms where decisions about our laws, public policy, and commercial transactions are made. It informs how I approach the study of law.

Ultimately, what those rallies represent to me are an effort by individuals, emboldened by the current administration, to attempt to recreate an era when bigotry and racism were woven more comfortably into the fabric of everyday life.

What should not be lost upon us is that depending on one’s identity, status and location, overt racism has never stopped being a reality. Furthermore, the systemic injustices faced by certain residents of Charlottesville and those everywhere else continue to thrive in our policies, laws, and practices.

My hope is that, as a community, we can and will fight for the freedoms of our most marginalized with the same fervor that we defend all Americans’ right to freedom of speech and expression.

Michele St. Julien is the Social Action Chair for the Black Law Students Association at the University of Virginia School of Law.

Karim Ginena: I wasn’t going to sit and watch as bigots came to my town

As a Muslim who is active in the local community and cares about social justice, I know all too well what it feels like to be disenfranchised. But still, I never imagined that one day I’d be protesting the KKK and white supremacy in my town.

One month before the events of August 11 and 12, 2017, several hundred protesters and I were faced with this grim reality when 50 Klan members showed up in downtown Charlottesville wearing Klan robes, carrying Confederate flags, and screaming, “White power!” Although this KKK rally gave fuel and encouragement to the alt-right rallies of August 11 and 12, it received more limited media attention.

My wife and I were blessed with a child just weeks before the July rally, and she was opposed to me attending these protests, counterprotesting, out of concern for my safety. I understood, but I had to go anyway, as I felt a need to fulfill my communal responsibility of voicing opposition. I wasn’t going to sit and watch as bigots preached their ideology in our backyard.

In the months after August 12, I served alongside leaders from other faiths and minority groups in a newly formed Charlottesville Community Leadership Council, a group that aimed to strengthen community bonds through outreach and collaboration. We hosted dialogues across our city.

As I reflect on the state of America at the one-year anniversary of these events, I realize that the rhetoric and policies adopted over the last year have hurt individuals and families. They have resulted in further racial segregation, as well as a rise in bigotry and inequality. That is painful to realize, but I can’t let it stop me. If we, the people, aspire for a better America with equal justice for all, then we must be willing to stand for our ideals, put them first, and work together toward a better future!

Karim Ginena is a Ph.D. candidate in management at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. He served as the outreach secretary on the board of the Islamic Society of Central Virginia at the time of the August 11 and 12, 2017, events in Charlottesville. He has been named a young policy professional by Harvard Law School’s Institute for Global Law and Policy and an emerging scholar by the Society for Business Ethics.

Amanda Moxham: It woke me up to the conversations we MUST have with our children

On August 11, 2017, I watched in horror via live video as torch-bearing Nazis marched across the grounds of the University of Virginia and violently attacked students and community members. On August 12, I provided childcare for counter-protestors while assisting with information flow as white supremacist violence tore through downtown. Juggling a need to create a day free of fear for the younger children while keeping the teenagers aware of any key actions downtown required an immense amount of calm and composure. In retrospect, it was eye-opening to realize how unprepared I was for this level of communication. Since that time, I have intentionally engaged in unpacking systemic racism and implicit bias with my children in ways I never knew I could. That day really woke me up to critical conversations that we MUST be engaging in with our children.

The events as they unfolded triggered in me fear, anxiety, anger, and ultimately in the days that followed—action. I immediately began learning and unlearning—unpacking my own deeply held biases about race and engaging in dialogue to understand how oppression was codified into law and are consistently upheld by government, legal, corporate, and educational systems.

Amanda Moxham is an organizer with the Hate-Free Schools Coalition of Albemarle County, a coalition of students, teachers, parents, and community members holding our school system accountable for dismantling racism from policy to the classroom.

Kibiriti Majuto: I felt like I was in a history book

I came to the United States from East Africa Democratic Republic of Congo to pursue a better life, but last year’s Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville has shown me that I cannot outrun white supremacy. Last summer, I couldn’t believe that I had to go protest the Ku Klux Klan in the 21st century. I felt like I was in a history book watching them march through my town in their white robes, an outward display of their disgust for my blackness.

The white supremacist attacks in Charlottesville showed that we have got to lay siege to both overt and covert white supremacy. It’s not just Nazis marching in the streets. It’s also the institutions that legitimize their views. Many people think the white supremacists attacked Charlottesville because it’s perceived as a liberal college town. But the real Charlottesville is a place plagued by a history of black displacement for white profit, massive racial disparities in housing and education, and a university that refuses to pay its black and brown service workers a living wage, which the board has continually delayed despite having an $8.6 billion endowment. [Editor’s note: Local media reported in June that UVA board members said new president Jim Ryan is working with community members on a living wage plan.]

When the white supremacists show up and show their hate, it’s a symptom of the underlying disease. As we approach the one-year anniversary of Charlottesville, I challenge you to confront white supremacy in all its forms, wherever it lies in your community.

Kibiriti Majuto is a student organizer and a board member with the Charlottesville Center for Peace and Justice. He attends Piedmont Virginia Community College and is a 2017 graduate of Charlottesville High School.

Mimi Arbeit: Posting on social media is meaningful, but it’s not enough

Anti-racist community members in Charlottesville scrambled for weeks before August 12 because we knew the Nazis wanted to kill people – they had made clear plans in their online message boards and had already been threatening Charlottesville leaders. We took evidence of the violent intentions of white supremacists directly to the city council, to no avail. In response, white liberal politicians demanded civility and expressed little concern. But no matter how we tried to send the message – protesting, shouting in city council meetings, or sternly presenting documented threats of white supremacists’ violent intentions – our desire to live, and to live without racial terror, was dismissed. As our democratic institutions succumbed to the fascist agenda, I called and called and called friends and other contacts who might have skills or resources to invest in anti-racist community organizing in Charlottesville.

When I talked to people outside Charlottesville about what was about to happen, they did not believe me, or did not understand, or did not push themselves to give me the help I was asking for. We needed (and folks still need) so much help: solidarity, strategy, mental health resources, financial resources, interpersonal connections, collaboration, child care, cooking. Put some food in someone’s freezer, so they have a good meal to microwave to get through the next crisis.

We need to let our lives be changed by the urgency of this moment. I can no longer conceive of my own personal and professional flourishing without daily joining with targeted communities to build power together, to flourish together. We need to dig deep to dismantle the foundations of white supremacy within our daily lives. This fight will require change, which requires loss. This year will continue to ask more from us than we maybe knew we had in us. Disagreeing with racism is not enough. Posting on social media is meaningful, but not enough. I need you to act with urgent outrage. Take care of each other and push each other to fight against fascism and for racial justice.

Mimi Arbeit is a former organizer with Showing Up for Racial Justice Charlottesville. In July 2018 she relocated to Boston, Massachusetts, where she will be an assistant professor of psychology.

Rachel Schmelkin: I learned a lot that day about what it means to truly support and protect each other

On August 12, 2017, I took a few cautious steps out of First United Methodist Church, a designated “safe space” for anti-Nazi demonstrators, to survey the park where Nazis were screaming ugly white supremacist chants. “Jews will not replace us!,” still rings in my ear as I recall that dreadful weekend. I’d never seen such hate up close, and for the first time I felt afraid to be a Jew in America.

A few days before the rally, I told my close friends, Reverends Phil and Robert that I was worried that I would be a target, but that it was important to be to be visible and present despite the risks. They promised me that they would watch out for me. They said “We will not let anybody get near you. In fact, we’ll stay with you as long as you’re out there. We will not leave you alone.” I trusted them, and they held to their word.

That day, I continued further out of the door and did my best to project songs of love and peace that might drown out the hate. With my guitar in hand and my brother standing next to me, we sang out “This little light of mine, I’m gonna let it shine!”

I learned a lot that day about what it means to truly support and protect each other, and to have others support and protect me. A black friend confided in me that she’s felt unsafe in her body her entire life. As a Jew, I felt that same visceral fear that August day in Charlottesville when neo-Nazis threatened to torch the Jews.

Anti-Semitism animates white supremacist ideology and is tightly integrated with its other racist and xenophobic views. Charlottesville’s “summer of hate” taught me that alliances across faiths, across race, across all kinds of differences are the best way to combat racism, anti-Semitism, and all types of bigotry and hate.

Since August 12, courageous citizens of Charlottesville have consistently come together to make Charlottesville a miserable place to be a white supremacist; they’re not welcome here.

Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin is with Congregation Beth Israel in Charlottesville.

Jalane Schmidt: We can’t let hate become normalized

On August 11, I was one of several people who warned the UVA administration that white supremacists planned to march that night. When that hour arrived, I was trapped on lockdown, with hundreds of others, in a church across the street from UVA while hundreds of torch-wielding white supremacists descended, some of whom assaulted my students. University police looked on without intervening – which foreshadowed the next day, when the police stood by while marauding Nazis beat members of my community.

I already distrusted the police, because they’re too often not held accountable for their assaults on black civilians. That’s why I’m involved in Black Lives Matter. August 11th and 12th in Charlottesville broadened my existing critique of law enforcement: When we protested against white supremacy, the police allowed white supremacists to attack us. The way I see it, police aided and abetted white supremacy.

Afterward, I got involved in advocating for a civilian review board to oversee the local police.

The alt-right has a fascist ideology, and their hero is in the White House. When the alt-right come to rallies in Charlottesville, they wear MAGA hats, chant pro-Trump slogans and even shout “Russia is our friend!” We must be vigilant and protest racist hatred and authoritarianism, so they do not spread unchecked and become normalized.

Jalane Schmidt is an associate professor of religious studies at UVA and an organizer with Black Lives Matter Charlottesville.