Story highlights

In Vogue, Beyoncé opens up about pregnancy complications and emergency C-section

The risk of pregnancy-related complications is higher among black than white women

To many, Beyoncé is the history-making superstar who “runs the world” with 22 Grammy Awards to her name – and hot sauce in her bag.

Yet last year, on the day she gave birth to twins Rumi and Sir, she faced a health scare.

Queen Bey was swollen from what she called “toxemia” or preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication that involves high blood pressure and protein in the urine, estimated to affect about 3.4% of pregnancies in the United States.

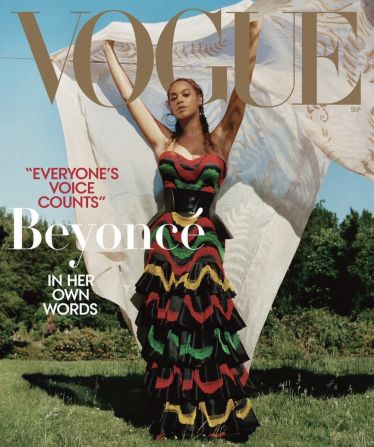

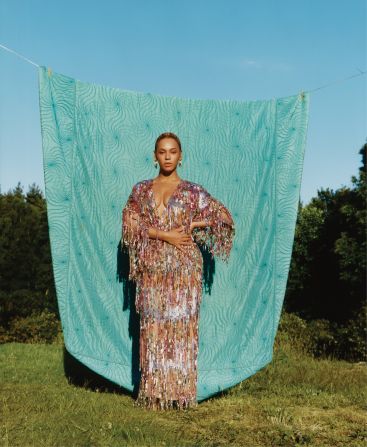

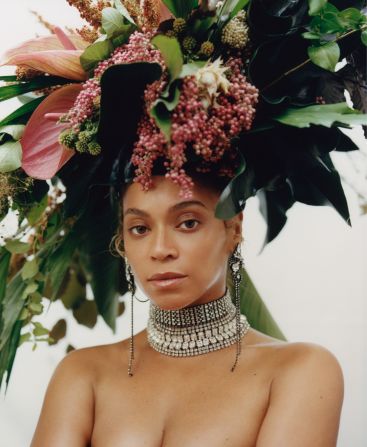

Due to the complication, 36-year-old Beyoncé had been on bed rest for more than a month before having an emergency cesarean section because her and her babies’ health were in danger, she said in Vogue magazine’s September issue, which debuted online Monday.

“Today I have a connection to any parent who has been through such an experience. After the C-section, my core felt different. It had been major surgery,” said Beyoncé, who also was featured on the magazine’s cover.

“Some of your organs are shifted temporarily, and in rare cases, removed temporarily during delivery. I am not sure everyone understands that. I needed time to heal, to recover,” she said. “During my recovery, I gave myself self-love and self-care, and I embraced being curvier. I accepted what my body wanted to be.”

Similarly, Serena Williams underwent an emergency C-section last year.

Williams, a history-making tennis star with four Olympic gold medals, also made a cameo in Beyoncé’s visual album “Lemonade” in 2016.

Yet last year, after the 36-year-old gave birth to daughter Olympia, she developed blood clots in her lungs. In an opinion article that Williams wrote for CNN in February, she described how she “almost died.” Williams has a history of blood clots and stopped taking her blood-thinning medication in order to help her C-section wound heal.

“What followed just 24 hours after giving birth were six days of uncertainty,” she wrote. Those days included a pulmonary embolism, or blood clots in the lung, that led to such intense coughing that Williams’ C-section wound popped open.

“I returned to surgery, where the doctors found a large hematoma, a swelling of clotted blood, in my abdomen. And then I returned to the operating room for a procedure that prevents clots from traveling to my lungs. When I finally made it home to my family, I had to spend the first six weeks of motherhood in bed,” Williams wrote.

“I am so grateful I had access to such an incredible medical team of doctors and nurses at a hospital with state-of-the-art equipment. They knew exactly how to handle this complicated turn of events,” she wrote. “If it weren’t for their professional care, I wouldn’t be here today.”

The two women’s chaotic and frightening childbirth experiences are all too real for the thousands of women in the US and around the world who face such complications during childbirth – complications that some don’t survive.

Every day, about 830 women around the globe die from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, according to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, about 700 women die each year as a result of pregnancy or delivery complications, and the risk of pregnancy-related deaths among black women is three to four times higher than among white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Black women often suffer more of these than do white women, in particularly the hypertensive diseases. So chronic hypertension, preeclampsia during pregnancy are more common among black women than white women,” said Dr. Elizabeth Howell, an obstetrician-gynecologist and professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who was not involved in Beyoncé’s nor Serena Williams’ care.

Beyoncé’s and Williams’ pregnancy stories have garnered much attention among men and women alike, with several people tweeting about the women’s bravery in opening up.

“Thank you to Serena, and now Beyoncé, for opening up about pregnancy complications and the toll it took on them. Everyone deserves access to healthcare, and to make their own pregnancy decisions,” wrote Dr. Daniel Grossman, director of the University of California, San Francisco’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health, in a Twitter post on Monday.

Marissa Evans, a journalist for the Texas Tribune, wrote in a Twitter post on Monday that having both Beyoncé and Williams talk about their pregnancy complications as black women within months of each other is “powerful” and shows how “maternal morbidity is unkind to so many black moms.”

To reduce this disparity, Howell said, there have been efforts to establish standardized protocols, called patient safety bundles, across hospitals in the US.

“We have what we call bundles that we’re doing within hospitals right now to try to target those conditions, to standardize care, to make sure that people get the appropriate care, and there’s less variation,” Howell said. “So that’s something that’s important that we stress and make sure that our patients are aware of, that hospitals are now implementing these.”

She added that advocacy – whether it’s a patient advocating for herself or women advocating for each other – also remains important in addressing issues related to maternal health and maternal mortality.

In Williams’ case, she said that she had to push her medical team to conduct a CT scan in order to check for clots.

Join the conversation

“Every mother, everywhere, regardless of race or background deserves to have a healthy pregnancy and birth. And you can help make this a reality,” Williams wrote in her CNN opinion article in February.

“How? You can demand governments, businesses and health care providers do more to save these precious lives. You can donate to UNICEF and other organizations around the world working to make a difference for mothers and babies in need. In doing so, you become part of this narrative,” she wrote. “Together, we can make this change. Together, we can be the change.”