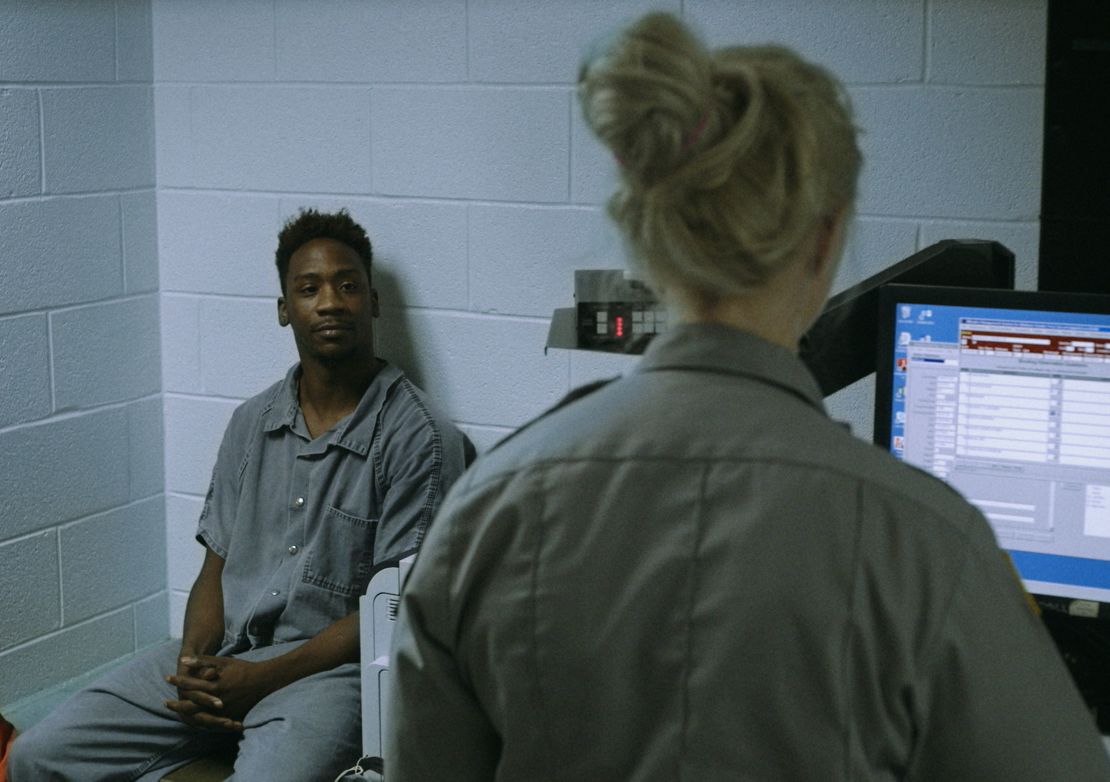

Lisa Ling examines how the court system treats women in Sunday’s episode of “This Is Life” at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

Year after year, the United States beats out much larger countries – India, China – and more totalitarian ones –Russia and the Philippines – for the distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world.

According to a 2018 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), nearly 2.2 million adults were held in America’s prisons and jails at the end of 2016. That means for every 100,000 people residing in the United States, approximately 655 of them were behind bars.

If the US prison population were a city, it would be among the country’s 10 largest. More people are behind bars in America than there are living in major cities such as Philadelphia or Dallas.

But after decades of explosive growth, there are signs that the country is turning the corner on mass incarceration.

The prison population decreased in 2016 for the third straight year, and prison reform, in general, is one of the rare issues with bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and in the White House.

On the other hand, approximately $80 billion is still spent each year on corrections facilities alone, according to a Prison Policy Initiative report, dwarfing the $68 billion discretionary budget of the Department of Education.

Clearly, this issue is complicated.

To better understand who the system impacts, it requires looking beyond the big numbers. Here are five key facts that bring the scope of the criminal justice system into focus.

Most inmates are held in state prisons and local jails – not federal prisons.

Prison reform solutions often focus on the federal government, but the vast majority of incarcerated people are held in facilities controlled by state and local governments, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

The nonpartisan think tank found that more than 1.3 million people are held in state prisons, while more than 600,000 people behind bars are in one of the country’s 3,000+ local jails.

These jails – sometimes dubbed the “front door” of the criminal justice system – often hold people who haven’t yet been convicted of a crime.

In many cities and states, money often decides who stays in jail and who gets out.

The BJS reports that in 2016, nearly two-thirds of all inmates in local jails were not convicted.

So why were they behind bars?

Many who are arrested and go to jail are able to get out quickly by simply posting bail. But those who can’t afford it are essentially trapped – they either sit in jail until the court takes action, or work with a bail bond agent to secure their freedom (with the latter option often saddling them with debt).

Advocates will quickly point out how this system puts the poor at a huge disadvantage. Stuck in jail because they can’t afford to pay bail, inmates are unable to work or support their families, making them particularly susceptible to the spiral of debt and incarceration.

The bail bond business, as with others tied to the criminal justice system, is extremely lucrative, bringing in more than $2 billion in profit each year, according to a 2017 report by nonprofit civil rights advocacy group Color of Change and the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice.

The ‘war on drugs’ isn’t solely to blame for mass incarceration.

Some have said that the “war on drugs” is responsible for America’s massive prison and jail populations.

And while this rings true in many federal prisons – where nearly half of all inmates are locked up for drug charges, often serving lengthy sentences – it’s a different story in state prisons and local jails.

In these facilities, where the vast majority of incarcerated people are housed, Prison Policy Initiative says those held for drug offenses are a much smaller proportion of the overall population.

But this still oversimplifies the relationship between drugs and mass incarceration.

For one, there is huge variation from state-to-state in how drug policies are enforced, according to a Pew analysis. States like Louisiana and Oklahoma, for instance, lock up drug offenders at rates far exceeding most others.

Though drugs may not be the primary reason most people are in state and local prisons, law enforcement agencies around the country are still making drug arrests in huge numbers.

In 2016, drug arrests actually increased about 10% from the previous year to more than 1.25 million, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report.

Once you’re in the criminal justice system, it’s often difficult to get out.

For some, just one arrest is enough to get caught up in the system.

There have been several studies on recidivism, but one of the most extensive was released in 2016 by the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC), which tracked more than 25,000 federal offenders over an eight-year period.

Officials reported that nearly half of those monitored were rearrested for a new crime or for a violation of supervision conditions. And for about half, it took less than two years for them to run afoul of the law again.

Other studies have found correlations between the length of a person’s rap sheet and the likelihood of recidivism.

A 2017 USSC study showed that offenders without any previous contact with the criminal justice system had an 11.7 percent lower recidivism rate than those with at least some prior contact with law enforcement.

Minorities are still overrepresented in the prison population, but racial and ethnic gaps are shrinking.

It has been a defining characteristic of the criminal justice system for years, and it’s still the case today: compared to the racial makeup of the overall US population, African-Americans continue to make up a disproportionate amount of the prison population. (Nonprofit organizations such as The Vera Institute have written extensively about this issue.)

Though African-Americans comprise only about 12% of the total US population, they represent 33 percent of the federal and state prison population. That’s compared to whites, who constitute 64% of American adults but just 30% of those behind bars, according to a Pew Research analysis of Bureau of Justice Statistics data.

But as the overall incarcerated population has slowly retreated from its peak in 2009, a shift is happening in American prisons: the disparity between the number of African-Americans and whites locked up is shrinking.

Between 2009 and 2016, Pew’s analysis shows the African-American prison population fell 17%, exceeding the 10% drop in the number of whites behind bars. The Hispanic population was virtually unchanged over the same period.

There are a number of ideas about what’s behind this closing gap, from stiffer law enforcement in rural, predominately white areas, to the scourge of opioids and heroin, which have hit white communities hardest.