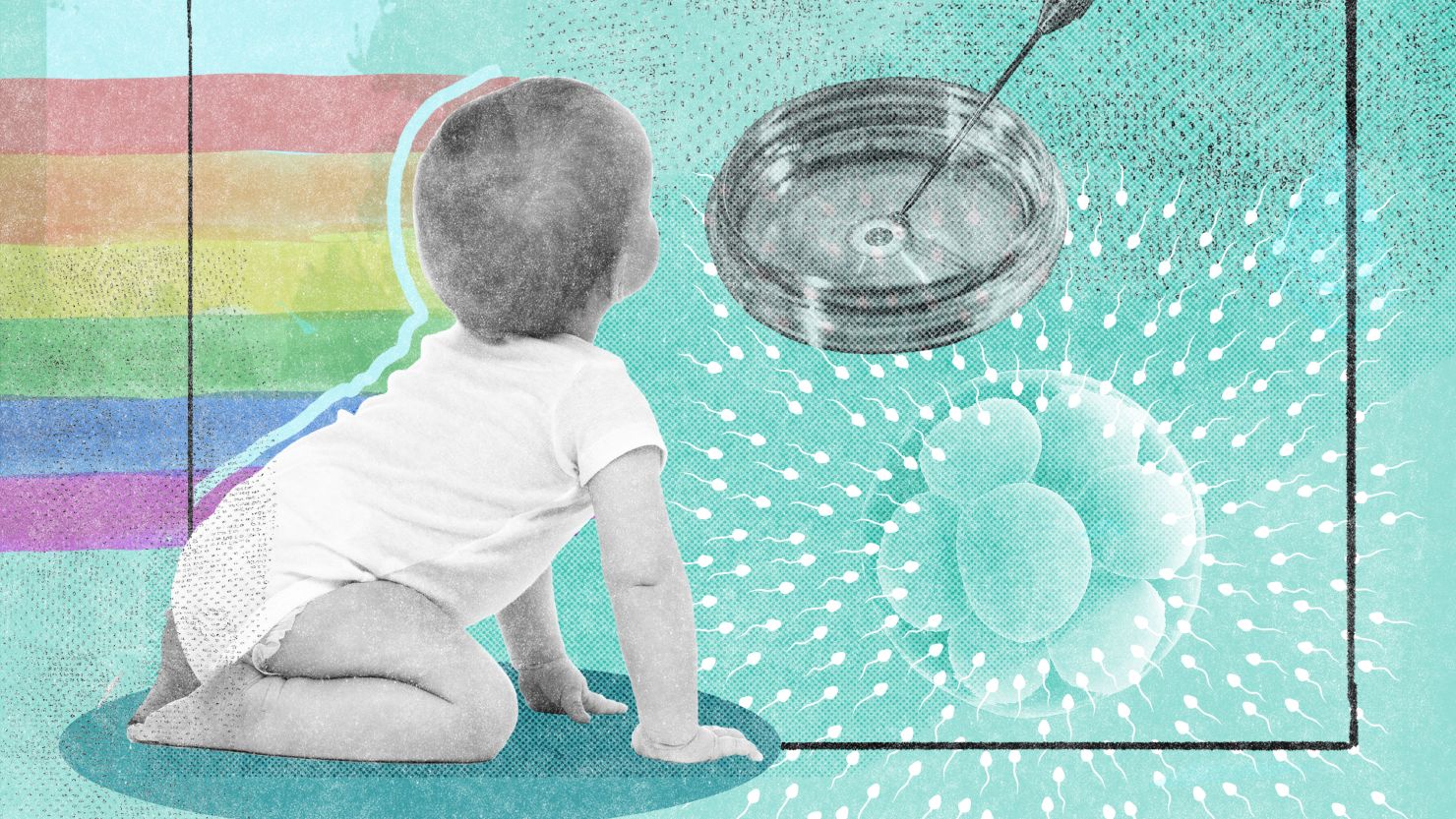

Their first date was over lunch during a Proposition 8 protest, where they joined hundreds of others railing against the passage of California’s same-sex marriage ban. The two men took a break from demonstrating, threw their hearts on the table and talked about their desire to have kids.

So it was somehow appropriate that in June 2013, nearly five years later, Bill Taroli and Yang Li stood in a delivery room and welcomed their son, Henry, one day before the US Supreme Court overturned Prop 8. A couple weeks later, with their newborn in their arms, they exchanged vows and were legally married.

Having Henry required careful and complicated planning over the course of several years. To become fathers, they needed a support group, legal help, extensive research, reams of documents, reproductive science and about $150,000. But none of that mattered without the help of two women: an egg donor and a surrogate.

One embryo brought them Henry. Five remaining healthy embryos they kept frozen in storage at the Pacific Fertility Center in San Francisco. They imagined the sibling they might someday give their son and stayed in touch with the women who’d helped give them life once – and might again someday.

Then came the news in March. A freezer or cryogenic storage tank at the facility failed, causing the level of liquid nitrogen to dip too low and the temperature to rise. The malfunction jeopardized the status of thousands of eggs and embryos inside, potentially crushing the dreams of hundreds of hopeful parents and families.

The fate of their embryos would prove significant not just for the fathers but for the women invested in their journey.

The eggs she wasn’t using

Taroli, 47, was adopted by his stepfather and was 20 when he first met his biological dad. When he considered pathways to fatherhood, he was open to a variety of options.

Li, however, was keen on having a biological child, making the decision of how to proceed easy, Taroli said. Henry “got his sperm and my name.”

They scrolled through a registry of possible egg donors provided by the fertility center, studying pictures and written statements. They settled on “Isabelle,” a name chosen by the potential donor, and elected to sit down with her in person.

She was a college student living in Sacramento when she spotted an ad about egg donation. She didn’t need to do it financially, as she had family support and scholarships, but she liked the idea of extra spending money and looked ahead toward medical school and the enormous expenses to come.

Isabelle, the name she preferred to go by for this story, also thought about how fixated she was on not getting pregnant, and her mind turned to those who wanted nothing more.

“Some people are tying so hard to not have something that other people would absolutely love to have happen to them,” she said by Skype from the United Kingdom, where she’s beyond medical school and now doing her residency in Wales. “I thought, ‘I have these eggs. I’m not using them. Someone might as well.’”

She also liked the idea of taking part in social innovation and helping families who, without someone else’s eggs, might never have children.

Isabelle’s mother was befuddled by and against her daughter’s decision to donate eggs.

“No, no, no – don’t do it,” Isabelle remembered her pleading. “What’s the point?”

She ended up going through six egg donation cycles and received $7,000 to $8,000 each time, she said. She was fascinated by the science of it all. Her pre-med friends lined up to give her hormone injections.

Most of her donation cycles went directly to a frozen egg bank, where they’d be used by people she’d never know or meet. But her first cycle, the experience she appreciated most, went to two men who chose her.

She was excited to meet the people “who wanted my eggs to be part of their family,” she said. When they got together in the clinic offices, Taroli did most of the talking and peppered Isabelle with questions. Li, who didn’t want to speak for this story, sat by with a clipboard, she remembered. The few questions Li asked were specific: He wanted to know what it was like to grow up bilingual and multicultural.

Isabelle, now 29, has a Portuguese mother and an American father. Henry has American and Chinese dads. And although their backgrounds are different from those of her parents, the couple saw in Isabelle a commonality. She walked away struck by their kindness and thinking how lucky any child of theirs would be.

Capable but ‘not interested in carrying my own’

They came to know their embryos well, including their sexes, through chromosomal testing and biopsies of their cells. Taroli explained that they received rankings, which measured their viability, and the ones they stored – including the one that would become Henry – represented their best chances to become parents.

Next, Taroli and Li had to identify their surrogate.

A traditional surrogate is implanted with embryos using her own eggs, but Taroli and Li opted for a gestational carrier, a surrogate who receives through in-vitro fertilization an embryo using somebody else’s eggs. The latter process, if they chose a carrier who also lived in California, would be less legally complicated for the gay dads, Taroli explained. The woman’s name would not appear on Henry’s birth certificate. Instead, both of their names would.

A few hours north of Castro Valley, the community in the East Bay where Taroli and Li live, the woman who would become their surrogate and her husband were happy to be parents to an only child. But she comes from a big family, in which the women generally have five or six kids, and her pregnancy had been “really, really easy,” she said.

An article she read about surrogacy got her thinking. Though pregnancy had been such a breeze for her, she knew that having a family was often a struggle for others. She thought about how some women feel attached to their babies while they’re in the womb and how she didn’t. It wasn’t until after her son was born that she made a connection.

The surrogate asked to be identified as “Audrey” to protect her privacy.

“I felt emotionally capable of being a surrogate. I felt physically capable,” Audrey said. “It seems kind of a waste that I’m so able to carry children but not interested in carrying my own.”

Her husband, whom she’s been with for more than 16 years, also didn’t want more children but was in full support of this idea. His mother, Audrey said, was initially disappointed because she still held out hope that they’d give her more grandkids. Audrey’s mother and grandmother, however, were completely on board.

It was her father, divorced from her mother and living several states away, who had the hardest time understanding. The thought of his daughter delivering somebody else’s baby, and being part of a process that might include the destruction of embryos, went against his faith. But the two of them had weathered points of friction before, and Audrey, then 30, was prepared to move forward.

It wasn’t about the money for her, although the $27,000 came in handy for the then stay-at-home mom.

She’d done research into how surrogacy worked and signed up with a surrogacy agency. There were questionnaires for her and her husband to complete, a psychological evaluation she had to clear and medical records that needed to be shared. She suspected that being a surrogate for a woman might become emotionally fraught and was most interested in being a surrogate for a gay couple. She also welcomed the chance to have an ongoing relationship after the birth.

The agency learned about Taroli and Li and set up a meeting.

With her husband and 3-year-old son with her, Audrey walked into the family-style restaurant the surrogacy agency had selected. It was initially awkward, sort of like heading into a blind date, she said.

“They brought me flowers, which was really sweet,” she remembered. “You could tell how much they were trying to impress me.”

Like her husband who works in IT, so does Taroli; Li is in software development. Their initial shyness was something she understood and liked. As they warmed up, they shared their histories, and the two men spoke openly about their hope to be fathers. They told her that they liked the idea of staying in contact with their surrogate, not just during the pregnancy but after, a proposition that made her smile.

She left feeling like, in them, she’d found her match.

‘Not just a vessel for their child’

After some additional testing at the fertility center, Audrey and the couple began to iron out a legal contract.

She laid out what she was – and wasn’t – comfortable with. She wanted to pick her own doctor and hospital. No more than two embryos could be implanted in her, she said, and she was relieved when they decided to go with just one. She planned to work with a doula, did not want an epidural and would consider a cesarean section only if the doctor deemed it necessary.

Eating healthy foods and not smoking were conditions she already chose to live by. And she and her husband would abstain from sexual intercourse in the weeks right before and after the embryo transfer, to make sure she was having Taroli and Li’s baby – not hers.

For many people, in vitro fertilization requires repeated tries – and additional costs – to work, if it works at all. The first embryo implanted in Audrey took without a hitch.

She, Taroli and Li were in touch by email a few times a week, and the dads came along to some of her doctor appointments. They got together at least once a month and came to know each other as her belly grew. Sometimes when they’d visit, the two men would take her and her family out to dinner.

“They really valued me,” Audrey said. “They saw me as a person, not just a vessel for their child.”

She recalled how her own child took the developments in stride. When he was nearly 4 and she was very pregnant, someone asked her son, “Aren’t you excited you’re going to be a brother?”

The young boy answered, without skipping a beat, “That’s not going to be my brother. That’s Bill and Yang’s baby.”

As her contractions grew stronger in the Redding delivery room, she held off on pushing and screamed out, “Are the dads here? Are they here?” A nurse rushed Taroli and Li in from the waiting room. They were there to witness Henry’s arrival and cut his umbilical cord.

Audrey and her husband, who was also in the room, watched as the two new dads fussed with how to put on the first diaper.

“They were so funny,” Audrey, now 36, remembered. “They were being a little snippy with each other. I’m sure I was like that with my son, and it was so cute to see that in someone else.”

Audrey pumped breast milk for Henry for 10 months and stopped sending the UPS shipments on dry ice only once Taroli and Li had enough to get them through their son’s first year.

She and her family visited Henry’s family quite a bit in the beginning. They saw them on Christmas and were at the boy’s first birthday party. They’ve since moved to Los Angeles, where Audrey works as a speech therapist. It’s been a couple years since they’ve seen each other, but they still get updates and pictures.

‘He’s not my son’

Isabelle and Audrey have not met but have heard about each other. They each received photo books Taroli and Li created to document Henry’s first year and how he came into this world. They receive updates and additional photographs, still. And, as a result, they’ve seen pictures of one another, as they’re both central to Henry’s story.

Isabelle remembers being a little thrown by the first photograph she spotted of Audrey.

“I remember thinking, she had my egg inside of her,” she said. “That’s just crazy.”

Isabelle didn’t see Taroli and Li again until Henry was about a 1?. The couple reached out to the clinic to say they wanted her to meet Henry.

“I wanted him to have the opportunity to know who was involved in his coming into being,” said Taroli, who didn’t learn that he was adopted until he was 14.

The clinic, in turn, put the query to Isabelle. She was living in the UK at the time but would be returning to California for Christmas.

Isabelle’s mother, who had opposed her daughter’s decision to donate eggs, suddenly couldn’t wait for her chance to meet the boy.

That would come later. The first visit with Taroli, Li and Henry was Isabelle’s alone.

As she drove across the Golden Gate Bridge, she began to grow nervous. She was fresh off a breakup, emotionally raw and worried that she might see Henry and suddenly want him. She feared that she’d lay eyes on him and believe, “This is my baby,” she said.

“But then, when I got there and I saw Henry, he couldn’t have cared less,” she said with a laugh. “I was just another person in the room. Yes, he’s genetically my son, but he’s not my son. He was more interested in the tissue box than me.”

She tries to see them whenever she’s in California and appreciates the photos they send her. Her mother gushes over pictures of Henry and “is probably more attached to him than I am,” Isabelle said.

Sometimes she wonders, if Taroli and Li had had a girl, whether she would have seen herself more in the child. She knew that there was a female embryo in the tank and thought about what might come later.

Taroli and Li told her, at one point, that if she ever found herself single or struggling to get pregnant, she was welcome to use embryos they didn’t use.

“It would be quite ironic, wouldn’t it?” asked Isabelle, who faces years of continued medical training and hopes to be an obstetrician-gynecologist some day. The option of using their embryos, if she needed them someday, stayed in the back of her mind.

An ocean between them

Taroli was texting with his mom, with his television on in the background, when a national story caught his eye. He recognized the lobby of the Pacific Fertility Clinic but thought it was just generic footage, he said, to complement a report on a failed fertility clinic storage tank in Cleveland, Ohio.

He had to rewind and watch the piece three or four times before the truth sunk in. The very same weekend that Cleveland experienced a tank malfunction, so did San Francisco.

He fired off an email to the fertility clinic, not knowing whether this freezer failure affected them. Li, who is establishing a new business in China, was abroad, so Taroli sent him a message, too, with a link to the TV segment.

A day or two later, Taroli said, he got a late evening call from the clinic, confirming that their embryos were in the ill-fated tank. To find out whether the embryos were destroyed, however, would take further testing.

To test an embryo requires that it be thawed first, which – in turn – might damage the embryo, Taroli explained. He and Li decided they would approve testing, one embryo at a time. If the first was still OK, they could hope that the others were, too.

“So we did that,” Taroli said over coffee in April. “They all came back dead.”

With thousands of miles and the Pacific Ocean between them, the couple processed what this meant for them.

“They were viable lives. They were potential babies, four boys and a girl, that if we chose to could have been our kids,” Taroli said. “It’s not about the death of a child; it’s not the same thing. … It’s the death of the possibility.”

And it’s the death of what might have been for Henry, who’d lost the chance to have biological siblings.

Taroli was playing the role of solo parent during Li’s China trip. He got choked up when he spoke about their son, who recently turned 5, and the extra big hugs he was getting.

“If I get upset, he cries,” Taroli said. “I’ve been careful not to talk about it in front of him.”

Breaking the news

It was important to Taroli to break the news to Isabelle and Audrey. They were part of the fertility journey from the start, and they deserved to know how it ended.

Before he got to Isabelle, though, she got an email from the Pacific Fertility Clinic. The clinic wanted to know, out of the blue, whether she’d be open to donating eggs again. She explained where she now lived but said she’d be interested if they wanted to talk. She got a call almost immediately.

If the clinic wanted to fly her to California or could wait until she was there for a visit, she said, she’d be willing to go through a donation cycle, she said. She was told they’d reach out again if they needed her.

The exchange got her thinking about Henry and her experience. She talked to a friend about it that night and wondered aloud about how big Henry must be.

When she woke up at 4 a.m., she said, she had an email from Taroli, telling her about the storage tank failure. She began to wonder whether the clinic had only called her because it had lost her eggs and their embryos. Taroli too found the timing odd. Why would they reach out to Isabelle without knowing whether he and Li were even interested in going through this again, he wondered.

The clinic, contacted several times for clarification on this and other questions, would not comment for this story.

The news of the lost embryos both shocked and saddened Isabelle.

“For some reason, I kept thinking about the little girl egg,” she said, and the potential that was lost for all the embryos. “They would never become people. But then, I guess, we always knew that they wouldn’t all ever become real people, right?”

Isabelle told Taroli that if he and Li ever wanted to try again, her eggs were theirs.

Audrey’s heart sunk too for the couple when she got the news from Taroli. She knew from a previous conversation that they were on the fence about when – or if – they’d have a second child, but she hated that the option was taken away from them.

Because her experience with Taroli and Li was so wonderful, Audrey went on to be a gestational carrier once more a few years later. But the second time she did it for an opposite-sex couple, and the experience was awful in comparison. That couple demanded that doctors speak only to them and wanted to manage all aspects of her life. Audrey felt like nothing more than a vessel.

After that, she said, she couldn’t imagine being a surrogate again – unless it was for Taroli and Li.

“They were so great, and I love them so much,” Audrey said. “I would do it a million times over again for them.”

Taroli and Li knew this.

‘Happy with where we are’

Pacific Fertility Center formally offered to cover all costs for another round, and their doctor, whom they don’t blame in any way, was eager to have them go through the process again.

But Taroli and Li, after processing the shock, mourning the loss and coming to terms with where their lives are now, have decided they aren’t interested in going through this again.

Join the conversation

They’re getting older, they love their life with Henry, Li’s new business in China will require lots of travel and time apart, and now is not the time for them to have more children.

The truth is, they may have never used those embryos, but they would have liked to make that decision on their own terms.

“If we were really eager to have a second child still or didn’t have Henry yet, our thinking might have been different,” Taroli said. “We’re happy with where we are.”

Meantime, attorneys are signing on clients for lawsuits against the clinic, but Taroli said they can’t imagine dragging this out. They don’t need to take part to find closure. Yes, they want to understand what went wrong with the tank that held their embryos, most of all because they want to be sure it doesn’t happen again.

“I work in tech, where lives aren’t on the line,” Taroli said. “You improve your process and put something better in place until the next thing you couldn’t anticipate happens.”

He doesn’t judge those who are seeking legal remedies, and he knows that for some, for instance those who froze embryos before undergoing treatment for cancer, what happened is a tragedy of different proportions.

But for him and Li, they will love the child they do have, stay honest with Henry about where he came from and give him every chance to know the women who helped him get here.

And someday, when the time is right and he asks why he never had siblings, they’ll find the words to explain.