Story highlights

In an open letter, experts and advocates call for public health efforts to eradicate HTLV-1

"There's just not much outside knowledge of it," says woman who lost father to cancer caused by the virus

It was a mystery illness to them.

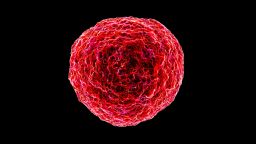

No one in the immediate Kurian family had heard of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, HTLV-1, before patriarch George was diagnosed with blood cancer. Doctors told the family that his cancer was due to HTLV-1, which can cause leukemia and lymphoma in some patients.

“I started Googling. I knew nothing about it whatsoever,” said Asha Kurian-Farris, George’s daughter, who is based in California.

“It was amazing to me that it had been around, or at least people had known about it for 40 years at this point, but there’s just not much outside knowledge of it,” she said.

The first detection and isolation of HTLV-1 was in 1979, and the discovery was published in 1980. Decades later, in 2015, Kurian died of his cancer, which doctors believed was caused by the virus. Now, Kurian-Farris says she knows that her father – a man from Kerala, India, with a big heart and a big love for science – would want more awareness raised about the virus.

“He was just hoping that he could contribute knowledge to this larger puzzle,” said Kurian-Farris, who is HTLV-1-negative and suspects that the virus was transmitted to her father from his mother. The virus can spread from mother to child, particularly through breastfeeding.

‘I don’t blame WHO at all. I blame us’

HTLV-1 – an ancient virus that can be found in 1,500-year-old Andean mummies – is associated with several serious health problems, including diseases of the nervous system and a lung-damaging condition called bronchiectasis, and it weakens the immune system.

The virus also can spread between sexual partners, through unprotected sex; and by blood contact. Sometimes, it is referred to as a distant cousin of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1, HIV-1.

On Thursday, an abbreviated version of an open letter – signed by 60 physicians, scientists and HTLV-1 advocates from around the world – was published in the journal The Lancet, calling for the World Health Organization to implement five strategies to help prevent the spread of the debilitating and deadly virus.

The strategies include testing for HTLV-1 in sexual health clinics, testing for the virus in blood and organ donations worldwide, testing in routine prenatal care and advising against breastfeeding by infected mothers.

A public focus on HTLV-1 has come about in recent years as an extremely high prevalence rate, exceeding 40%, has been detected among adults in remote central Australia, with indigenous communities being the hardest hit, especially in the town of Alice Springs.

“We need WHO to make noise on this, to be aware of it, to make sure all health communities know about it, to push testing for it, et cetera, and we need (the US National Institutes of Health) and others to promote funding for it to make up for lost years of poor funding,” said Dr. Robert Gallo, co-founder and director of the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, whose laboratory was the first to detect HTLV-1.

“I don’t blame WHO at all. I blame us for not making enough assertion, with enough strength and enough potency, regarding the importance and the damage that this virus can do to an individual,” said Gallo, who is also co-founder and scientific director of the Global Virus Network and co-chairman of the GVN HTLV-1 Task Force.

“It’s time to really correct that,” he said.

A family comes face-to-face with HTLV-1

A first sign that Kurian was carrying the HTLV-1 virus emerged in the form of mouth sores, his family said. He visited a dentist and his doctor, but the sores came and went every few months.

Kurian’s doctors took a closer look. They noticed a high white blood cell count and continued medical testing. They found HTLV.

In the days after Kurian’s diagnosis, his family searched for treatment options.

They applied for him to get a “compassionate use” exemption from the US Food and Drug Administration so he could be treated with a drug approved in Japan called mogamulizumab, which was found to target HTLV-1-infected cells. The FDA agreed, but the pharmaceutical company in Japan refused to release the drug, Kurian’s family said.

Now, they hope his story illustrates the need for more research.

‘They’ve been orphaned’

There is no cure and no vaccine for HTLV-1, but some scientists around the world are hoping to change that.

“Our research group has primarily focused on trying to better understand how HTLV-1 replicates, with the ultimate goal of trying to develop new therapeutic strategies to prevent virus spread and transmission – and that’s one of the open areas that’s not been well-supported globally,” said Louis Mansky, a professor and director of the Institute for Molecular Virology at the University of Minnesota, who was not involved in the new letter.

“The number of researchers is fewer than you would expect for such an important human infectious agent that causes cancer, as indicated in the open letter,” he said. “The awareness of it and the support for research to better understand its prevalence, and for treatment of the viral disease, has lagged behind compared to some other viruses: HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus.”

HTLV-1-infected patients often contact Mansky’s lab, seeking new developments in treatment, and so he has seen their plight first-hand.

“Infected patients and loved ones feel as if they’ve been orphaned,” he said. “So for those who are not infected or they do not know somebody who is infected, it may not have an impact on their lives, but when it’s you or a loved one, it can make all the difference in the world.”

Although the virus can be found throughout the world, there are certain endemic areas, such as the isolated cluster in central Australia.

The main highly endemic areas are the southwestern part of Japan; some parts of the Caribbean; areas in South America, including parts of Brazil, Peru, Colombia and French Guyana; some areas of intertropical Africa, such as south Gabon; some areas in the Middle East, such as the Mashhad region in Iran; a region in Romania; and a rare isolated cluster in Melanesia, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Elsewhere in the world, such as in the United States and the UK, prevalence remains low.

‘I do believe it is possible to eradicate HTLV-1’

More research is needed to determine the true global prevalence of the virus, Gallo said, adding that he wonders about prevalence in other regions in the Middle East, Africa, Russia, China and South America.

“So, there are still unknowns. This has been a way under-studied and a way underfunded problem,” he said, adding that there are several reasons why HTLV-1 has become a neglected virus.

“The major reason has been that it doesn’t efficiently transmit. Even though its mechanism of transmission is very much the same as HIV, it’s much less efficient,” he said. “And it’s maintained itself in certain populations,” where not much medical attention has been provided.

Many regions around the world affected by HTLV-1 are poorer communities that often go overlooked by the medical establishment and don’t have as many health care resources, Gallo said.

Join the conversation

“I believe that now is a critical time to support continued research and application of that research to take us over the goal line in the fight against this deadly virus,” said Susan Marriott, a professor in the Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the open letter.

With additional work, she believes, it is possible to eradicate HTLV-1 around the globe, but it will be difficult.

“First, the virus may not be detected until a patient shows signs of disease, which can be 40 or more years from the time that they were infected. During these 40-plus years, an infected person can unknowingly spread the virus to others,” Marriott said.

“Second, some of the people who are most affected today live in remote parts of the world with minimal access to early detection options and state-of-the-art health care,” she said. “I do believe it is possible to eradicate HTLV-1 from the world population, but it will be a challenging task.”