Story highlights

The $20 billion Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is the world's longest sea-crossing bridge.

The bridge is a central plank in China's ambitious plans to develop the Greater Bay Area.

Although the bridge is an engineering marvel, its construction has been dogged by controversy.

As we drive down the eerily deserted Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, the murky waters of the Pearl River Delta stretch as far as the eye can see. There is no land in sight.

Spanning 34 miles (55 kilometers), this is the longest sea-crossing bridge ever built. Gao Xinglin, assistant director and senior engineer at the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Authority, meets us half way along. As we are buffeted by a strong wind, the tough conditions his construction crew experienced, as they perched on precarious platforms, working miles from land and high over the water, are evident.

Gao is visibly proud of his country’s monumental achievement.

Due to open to the public this summer, this long snake of bitumen will connect a relatively small city on the Chinese mainland with the two Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau.

But since the bridge was first suggested in 2003, it has stirred controversy. This massive span of concrete and steel is not just proof of China’s ability to build record-setting megastructures – it’s also a potent symbol of the country’s growing geopolitical ambitions.

As tensions simmer between the mainland and Hong Kong and Taiwan, and China continues to claim territory in the South China Sea, the bridge can be seen as a physical manifestation of the Chinese leadership’s determination to exert its regional influence. Critics have also questioned the environmental and human toll and the immense financial cost of the project.

China’s Greater Bay Area

Building the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge

The Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge is a central plank in China’s master plan to develop its own Greater Bay Area – a region it hopes will develop to rival the bay areas of San Francisco, New York and Tokyo in terms of technological innovation and economic success. The official narrative is that greater regional integration will drive economic growth.

Home to 68 million people, the Greater Bay Area covers 21,800 square miles (56,500 square kilometers) in central southern China, and encompasses 11 cities – Hong Kong, Macau and nine cities across Guangdong province.

Marcos Chan, head of research for commercial real estate consultancy CBRE Hong Kong, Southern China and Taiwan, says the region is already very vibrant and economically productive. “It takes up less than 1% of the land area of China and is home to less than 5% of the population but produces 12% of China’s GDP.” When compared to countries around the world, he says “the Greater Bay Area already has the 11th largest economy.”

The idea of a Greater Bay Area was first raised in 2009, but development has been hampered because “there are lots of barriers between the cities,” Chan says. The region incorporates three borders (Hong Kong/China; Macau/China; Hong Kong/Macau), three different legal systems and three different currencies. Additionally, residents carry three different passports and identity cards, and speak two different languages (Cantonese and Mandarin).

“To compete with other bay areas in the world, the Chinese government has to remove or reduce these barriers … and promote integration among the cities,” says Chan.

That’s where the bridge comes in. It will slash journey times between the three cities from three hours to 30 minutes, putting them all within an hour’s commute of each other.

“At present, the economic distribution is very uneven between the Pearl River Delta’s east and west coasts,” says Chan adding that, “the cities on the eastern side such as Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Dongguan are more economically developed than cities on the western side including Zhuhai, Jiangmen and Zhongshan.”

He says the bridge will make it easier for goods produced by factories on the west side to be exported from air and sea ports on the east side – including Hong Kong’s international airport, the busiest cargo airport in the world.

The bridge is also intended to boost tourism. “At present, visitors to Hong Kong from mainland China tend to fly in for one or two days, mostly for shopping, and seldom travel to other areas in the Pearl River Delta,” says Chan. Once the bridge is open, tourists – both from China and other countries – will be able to travel from Hong Kong’s airport to Macau and the mainland in about 45 minutes.

The big draw in Macau – a former Portuguese colony – is its casinos. “It’s the largest gambling city in the world, and the only city where gaming is legal in the whole Greater China region,” says Chan. Zhuhai, sometimes referred to as China’s Florida on account of its balmy climate and lush vegetation, is a family-friendly destination. Holiday resorts, theme parks and golf courses are currently being developed on the offshore island of Hengqin.

The bridge is not the only cross-border development underway. The Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link,which will connect Hong Kong to China’s high speed rail network, and the Liantang-Heung Yuen Wai Boundary Control Point, a border crossing between Hong Kong and mainland China, are both due to open later this year.

Chan believes the region could become “possibly the most attractive tourism hub in China.” But not everyone sees the benefits.

A white elephant?

“The bridge is a waste of money,” says Claudia Mo, an independent lawmaker who supports greater democracy in Hong Kong. “When it comes to linking the mainland to Hong Kong, we have air, sea and land linkages already. Why do we need this extra project?”

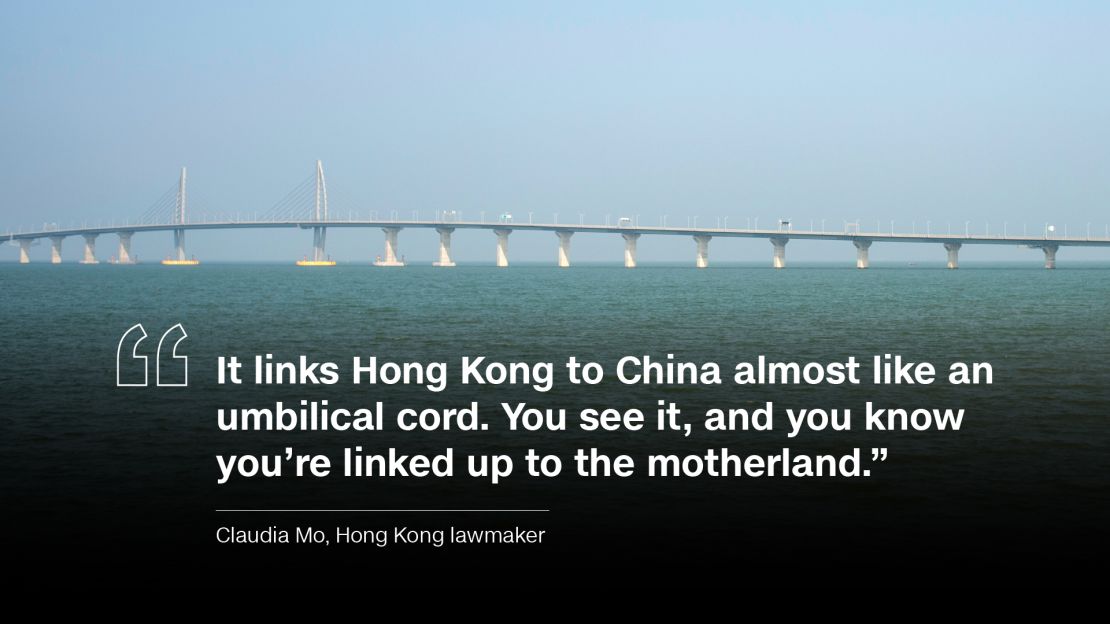

Like other critics, Mo believes that building the bridge was a political act. In the wake of Occupy Hong Kong – the 2014 pro-democracy protests which rocked the territory – Beijing has tightened its grip on the city. Opponents see the bridge as a means by which to force assimilation and exert control.

“You can’t see the existing transport connections – in a literal way. But this bridge is very visible … you can see it from the plane when you fly in to Hong Kong, and it’s breathtaking,” says Mo. “It links Hong Kong to China almost like an umbilical cord. You see it, and you know you’re linked up to the motherland.”

Mo says she is unsure that Hong Kong’s roads can cope with the extra vehicular trafficthe bridge will bring, and she believes the territory doesn’t need any more tourists. “Hong Kong is bursting. We already get more tourists than the whole of the UK.” In 2016, Hong Kong welcomed 56.7 million tourist arrivals, whereas the UK received 37.6 million overseas visitors.

Mo also believes that Hong Kong has spent too much money on the bridge. The three regional governments that collaborated on the project took financial responsibility for sections inside their own territories and shared the cost of the 14 mile (23 kilometer) long main bridge that runs between them.

Information supplied by the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Authority has revealed that the total cost of the main bridge was $7.56 billion, $4.32 billion of which was funded with bank loans. Of the remaining $3.24 billion, Hong Kong put up $1.38 billion – a little less than Zhuhai ($1.43 billion), which received financial support from China’s central government, and considerably more than Macau ($0.43 billion) which, with a population of 610,000, is the smallest of the three cities.

A spokesman at Hong Kong’s Transport and Housing Bureau told CNN that Hong Kong spent an additional $4.57 billion on its Boundary Crossing Facilities, and $3.19 billion on a link road from the main bridge to the boundary crossing. Hong Kong’s total bill exceeds $9 billion.

“Hong Kong has had to fund a lot of the bridge,” says Mo, “but we won’t see many benefits here.”

How to build a megabridge

Record-breaking bridges

While the true need for the bridge is disputed, it is undeniably an extraordinary feat of engineering.

Built to withstand a magnitude eight earthquake, a super typhoon, and strikes by super-sized cargo vessels, it incorporates 400,000 tons of steel – 4.5 times the amount in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.

Gao says the most technically difficult aspect was the construction of a four mile (6.7 kilometer) long submerged tunnel.

The tunnel is a crucial component because the Pearl River Delta is one of the busiest shipping areas in the world. According to the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Authority over 4,000 vessels – everything from passenger ferries to container ships – cruise its waters every day.

Gao explains that the tunnel is made of 33 “elements” – huge hollow blocks measuring 590 feet (180 meters) long, 125 feet (38 meters) wide and 37 feet (11.4 meters) high. Each element weighs 80,000 tons – about the same as an aircraft carrier. The elements were precast on Guishan Island, near Zhuhai, and transported to the construction site by floating pontoons and tugboats. “We excavated a foundation trench in the sea bed, laid a rock bed, then immersed the elements,” he says.

The tunnel runs between two artificial islands, each measuring one million square feet (100,000 square meters) and situated in relatively shallow waters. Building islands from scratch didn’t prove easy, either, says Xinglin. A structural frame was created using 120 giant, hollow, steel cylinders, each one 165 feet (50 meters) high (equivalent to an 17-story building) and weighing 550 tons – about the same as an Airbus A380, the world’s largest passenger jet.

“The steel structures were manufactured in a workshop in Shanghai and then transported to the site by ship,” Gao tells CNN. The team used hydraulic hammers to drive the cylinders into the seabed, then filled the cylinders and the enclosed area with sand.

Troubled waters

It’s no surprise that Gao admits to having suffered sleepless nights.

The bridge has been plagued by criticism since its beginning. Environmental groups including WWF and the Hong Kong Dolphin Conservation Society, for example, have argued that its construction has further endangered Hong Kong’s beleaguered population of Chinese white dolphins.

A spokesperson for Hong Kong’s Highways Department said: “The locations and alignments of the … infrastructure are carefully determined to avoid the Chinese white dolphin’s major active areas. Besides, the construction methods have also been carefully selected so as to minimize the impacts to the marine environment.”

The project’s worker safety record has also been criticized. In a statement, the Highways Department told CNN that seven workers had died, and 275 had been injured, while working on Hong Kong’s link road and boundary crossing facility. “The relevant requirements on occupational safety are included in the contract provisions of the public works contracts … Highways Department has also required contractors to strictly implement the safety measures.”

With every setback the official opening date – originally planned for late 2016 – has been further delayed, which led some to doubt whether the bridge would ever come to fruition.

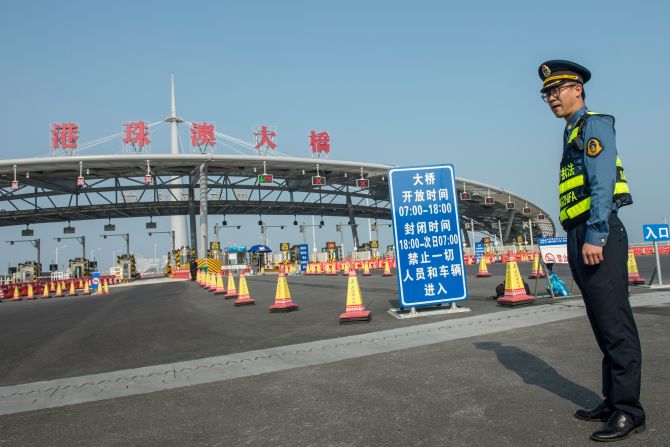

But with the main construction of the bridge now complete, officials are putting the finishing touches to the project – finalizing plans for customs arrangements and operations at checkpoint facilities, determining responsibility for emergency rescue operations, and negotiating toll prices.

The speed limit has been set at 62 miles (100 kilometers) an hour, and it has been decided that cars will drive on the right along the Chinese sections of the bridge, and switch to the left in Hong Kong and Macau, to match the driving styles in each city.

In a few months’ time, this empty ocean highway will be filled with cars, buses, trucks and lorries, zipping between China, Hong Kong and Macau. It remains to be seen if the boost to connectivity will elevate China’s Greater Bay Area to new heights, and how much further it will bring Hong Kong and Macau into China’s powerful embrace.