Editor’s Note: Jeff Yang is a frequent contributor to CNN Opinion, a featured writer for Quartz and other publications and co-host of the podcast, “They Call Us Bruce.” He co-wrote Jackie Chan’s best-selling autobiography, “I Am Jackie Chan,” and is the editor of three graphic novels, “Secret Identities,” “Shattered” and the forthcoming “New Frontiers.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own.

Prom dresses are designed to get reactions, and the history of social media is littered with viral prom outfits – dresses made out of unusual materials, dresses that send statements and dresses that are, well, regrettable, to say the least.

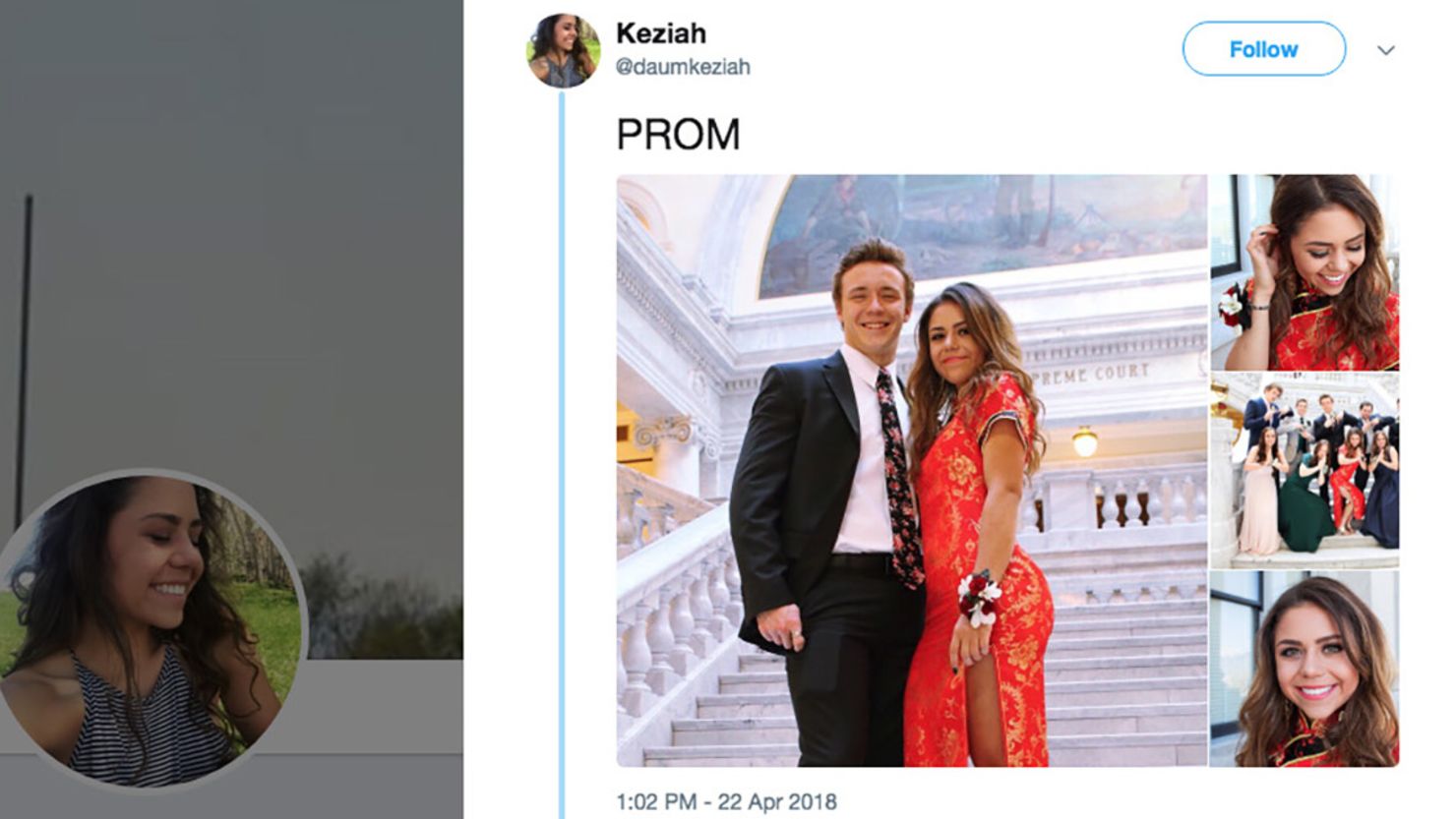

But the viral reaction 18-year-old Keziah Daum has sparked with her prom dress is shocking, in no small part because of its disproportionate intensity. Her decision to wear a Chinese outfit called (depending on your dialect) a qipao or a cheongsam to prom in Utah, despite having no Chinese ancestry – and then tweeting pictures of her posing with friends at prom -- has launched a social media debate around cultural appropriation that’s generated hundreds of thousands of posts and comments, many of them outraged, and some of them outrageous.

As she said to Buzzfeed, “I never imagined a simple rite of passage such as a prom would cause a discussion reaching many parts of the world,” Daum said. “Perhaps it is an important discussion we need to have.”

She’s right on that point: Cultural appropriation is a real and serious concern that’s deeply intertwined with issues like colonialism, labor theft, racial privilege and ethnic stereotyping. Dismissal of the phenomenon is often simply a knee-jerk reaction by those seeking to assail what they see as “political correctness.”

But as always with these discussions, it pays to consider context before opening fire.

Is it inherently appropriative for a non-Chinese person to wear Chinese-style apparel? The answer is: It depends.

Is the person wearing it as part of an attempt at racial aping, mockery or stereotyping (see: every Halloween ever)? Is the clothing itself an inappropriate variation of attire that’s worn for culturally essentialist or religious purposes (example: conical peasant hats or anything with the Buddha stamped on it)? Is the outfit being worn to an event whose theme uses Asian aesthetics in the service of white establishment privilege (e.g., so many museum galas)?

And what, for that matter, are the actual origins of the garment in question?

Because the qipao, especially in its contemporary form, is far from a “traditional” Chinese outfit. In fact, it historically wasn’t “female” clothing at all — or even “Chinese.”

The outfit that became the qipao, the sijigiyan, was the traditional ethnic clothing of the Manchu, who took over China in 1644 and established their own Qing Dynasty as its rulers. In the process, they mandated that all adult Chinese men in service of the throne wear Manchu garb – turning the loose-fitting straight-line sijigiyan, known in Mandarin Chinese as the changpao, into both a symbol of elite status and a stamp of absolute Manchu domination.

Eventually, the practice of wearing changpao became common even among non-Manchurian Chinese men who weren’t part of the government. But non-Manchurian Chinese women continued to wear typical Chinese outfits – usually blouses and long skirts under loose coats or jackets – until the Qing Dynasty fell in 1911.

At that time, under the newly founded Republic of China, Chinese feminists called for women to end the practice of footbinding, cut their hair short and began wearing changpao as a means of asserting their equality with men.

By the 1930s, in colonial Shanghai and Hong Kong, the traditional Manchu male outfit had become feminized and stylized: The long gown was cut short and shaped to fit women’s curves, elaborately printed or embroidered and turned into the dress commonly referred to as the qipao. Today, Chinese women who aren’t restaurant staff or flight attendants do not wear the modern version of the qipao – skin-tight, with a revealing leg slit and a hemline above the knee – for anything other than weddings and gala events.

Which brings us back to Keziah Daum’s decision to wear a qipao to her prom. She clearly didn’t consider the full implications of her decision to not just wear the dress, but to post pictures of herself doing so on social media without explanation. And her comments to the press make it apparent that she hasn’t fully reflected on the way that wearing outfits or hairstyles associated with other cultures is itself an expression of privilege.

But in all fairness, her critics may actually be less knowledgeable about the dress than she is – after all, Daum has referenced the qipao’s association with female empowerment as one of the reasons she chose to wear it.

More importantly, those who have chosen to conduct a social-media pile-on of Daum rather than engage her in civil conversation forget that she’s a teenager – one whose interest in other cultures could easily be turned into respect, mutual exchange and positive engagement.

(Though the cultural context of Asians who live in a majority-Asian societies, versus Asian Americans who live as minorities in the US, is quite different, it’s worth noting that Chinese in China have largely stepped up to defend Daum’s wearing of the dress as a valid homage and celebration.)

Yes, cultural appropriation is something we need to discuss. But any “discussion” that involves thousands of strangers attacking a teen from the safety of distance and anonymity looks a lot like cyberbullying. What’s more, the incessant flame wars around Daum have prompted those on the extreme right to use her as a symbol to advance their agenda of cultural erasure.

Like prom dresses, posts on social media are designed to draw attention. But let’s remember that, like prom dresses, when they go wrong, the results can be … regrettable.