Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, 50 years ago on April 4, 1968, setting off a period of mourning, reflection and anger that gripped America. He was in Memphis to rally support for striking sanitation workers, who were protesting unsafe working conditions, and while on the balcony of his room at the Lorraine Motel (now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum), he was shot once and fatally by James Earl Ray, from the bathroom of a nearby boarding house.

By the age of 39, King had become a primary leader of the civil rights movement and had been active since the 1950s as a minister and founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was an instrumental figure in protests (in Montgomery, Washington, Selma and elsewhere) and in the passage of landmark civil and voting rights legislation. He had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at 35. In the last years of his life, King faced criticism from some African-American activists who wanted him to employ more confrontational strategies for change. At the same time, he had become more outspoken on issues of poverty and the need to end the war in Vietnam, significantly in the “Riverside Church” speech, delivered in New York a year to the day before his death.

The assassination reverberated powerfully around the world, especially in American cities, where the tragedy sparked unrest in Washington, Chicago, Baltimore, Kansas City, Missouri, and elsewhere. The following week, riots broke out in dozens of cities, in multiple instances warranting the intervention of the National Guard.

King’s death (like that of Malcolm X only a few years earlier) radicalized some activists who saw futility in his strategy of nonviolence. At the same time, widespread public mourning for King was key in the passage – only days after his assassination – of the Fair Housing Act, the final significant civil rights legislation of the era. President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill creating a national holiday in King’s name in 1983, and King’s vision remains the foundational lexicon of the fight for racial equality in the United States.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his assassination, CNN Opinion asked a diverse group of activists, academics, public figures and artists: What do you see as the most applicable part of King’s legacy? On this occasion, what do you most want to say about him?

The views expressed here are solely those of the authors.

King’s place in history is still unfolding

Sherrilyn Ifill: King’s work remains unfinished, but the democracy-building work continues

A decade before his shocking assassination, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on behalf of the Montgomery Improvement Association, sent a thoughtful letter and a $1,000 check to Thurgood Marshall, then director-counsel and founder of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF), the civil-rights organization I’m now blessed to lead.

King wrote that the purpose of the letter and the modest contribution — which he wished wasn’t so modest, perhaps because he knew the real costs of legal representation in the trenches — was to express his “deep sense of gratitude” for our work “for not only the Negro in particular but American Democracy in general.”

“You continue winning the legal victories for us and we will work passionately and unrelentingly to implement these victories on the local level through non-violent means,” King wrote, singling out our legal assistance in his organization’s struggle to help desegregate the Montgomery bus system.

This was no ordinary civic-legal partnership. If Brown v. Board Education spelled the doom of “separate but equal,” the lesser known Browder v. Gayle, which we helped litigate in Alabama just two years later, was the doctrine’s coup de grace — a unanimous Supreme Court declined to disturb a lower-court ruling invalidating a series of Jim Crow-era statutes and ordinances that provided for racially segregated buses.

What’s most touching to me about King’s letter to the LDF is that it came in response to legal victories that were, as he put it, victories for “American Democracy.” The rulings were a recognition, at long last, that the Fourteenth Amendment meant what it said when it was ratified in 1868. That the Constitution’s promise of equality — the command that no state could “deny to any person … the equal protection of the laws” — was meant for all of us, regardless of skin color. That exclusion of anyone on account of race could not be tolerated.

And yet, we’re still fighting to make our Constitution’s true meaning real. We’re still fighting to make sure no one’s vote is suppressed. We’re still suing to ensure that the Fair Housing Act, a law enacted in the very wake of King’s death, is enforced to its fullest extent. We’re still fighting school districts that believe a segregated education is in children’s best interests. We’re still fighting so that police departments that brutalize communities of color are held to basic principles of constitutional policing. We’re still fighting so that immigrants aren’t targeted for expulsion from this country.

Worse yet, when it is the president of the United States himself who is pushing an unconstitutional vision of America — by casting this struggle for basic dignity and equality as a political tool to denigrate black and brown people, all the while stoking white resentment and victimizing himself — it is clear that we’re far from living up to King’s ideals.

Today, 50 years since his death in Memphis, we’re in a moment. A moment when I truly believe we are being driven to confront that rot at the foundation of our democracy. A rot we have papered over for too long. It is weakening every pillar of our democracy — up to and including the highest office in our land.

Just a month before King’s death in 1968, Jack Greenberg, our second director-counsel after Marshall, met with Dr. King to discuss our next partnership: our representation of participants in the Poor People’s Campaign to advocate for fair wages, better jobs, employment training and more — the next logical step in King’s vision of true equality. That he was killed while leading such an effort among striking sanitation workers in Memphis is a tragic testament to what was destined to be the next phase of his legacy.

But to this day, I’m heartened as I look back on that civic-legal bond we shared, and his insight that our connection was “the most powerful and constructive avenue” to bring African Americans to their full measure as citizens. That much is still true today, or else we would’ve given up the fight a long time ago.

King’s work remains unfinished, but the democracy-building work continues — with lawyers and activists working hand in hand to reach the promised land that King saw but couldn’t yet enter.

Sherrilyn Ifill is the president & director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund Inc.

Joseph J. Ellis: The dialogue among Jefferson, Lincoln and King continues

Though it is only a conceit, I like to believe there is an ongoing dialogue on the Mall and Tidal Basin among Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. Jefferson started the conversation with the magic words of American history: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” He clearly intended the words to mean that slavery was wrong but never acted on that intention as a statesman or slave owner.

Lincoln did act, in a very big way called the Civil War. But Lincoln failed to take the next step by endorsing a biracial American society.

That was King’s mission. He believed that the meaning of Jefferson’s magic words had expanded to include blacks as well as whites. Though he delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he claimed he was collecting on a “promissory note” written by Jefferson.

Whether Lincoln would have felt upstaged by the Jefferson reference can never be known. It is possible that Lincoln heard King’s words in the “I Have a Dream” speech as an updated version of his own words in the Gettysburg Address, where Lincoln described “a new birth of freedom,” believing that his own words also had an expansive meaning.

Jefferson’s response to King’s speech is more difficult to imagine. In his own lifetime Jefferson was a truly visionary statesman who could endorse the complete separation of church and state as well as the global triumphs of democracy. But race was his blind spot.

Even though he watched four of his own biracial children by Sally Hemings grow up at Monticello, Jefferson went to his grave believing that blacks and whites could never live together in harmony in the United States. And if and when they did, the result would be the pollution of the Anglo-Saxon race, in his view.

In that sense, King’s dream was Jefferson’s nightmare. The white racist who shot King on the balcony in Memphis could claim to be acting in Jefferson’s name with as much plausibility as King himself.

On the other hand, Jefferson was a firm believer in what he called “generational sovereignty.” Though there surely were external truths, each generation needed to rediscover those truths for itself and not be held hostage to the past. History moved forward along a gradually ascending path that Jefferson described as “the progress of the human mind.”

King had his own way of describing the same idea. He borrowed the words from Theodore Parker, a 19th-century theologian and anti-slavery advocate: “The arc of the moral universe bends upward toward justice.” With these words in mind, I can easily imagine Jefferson smiling from his perch on the Tidal Basin when the Martin Luther King Memorial went up, welcoming him as the third and final member of America’s trinity.

In this uplifting version of American history, all three icons nodded their approval when the Museum of African American History and Culture was dedicated in 2016.

Anyone who toured the new museum, however, would be forced to confront the self-evident truth that Jefferson chose to omit from the Declaration of Independence, though he was candid enough to acknowledge it in his correspondence. Lincoln and Kingknew it too, and both of them were killed by men who felt it in their very bones.

Namely, American society rests atop a deep pool of racial prejudice that has defined the relationship between blacks and whites for most of American history. It is still there and always will be. The conviction that we can and should become a truly biracial society is a recent, mid-20th-century idea.

King was the chief apostle for that idea, which is the reason we honor him with a place on the Mall. But he knew that he would not live to see the Promised Land.

He also knew, as Jefferson and Lincoln knew, that the upward arc of the moral universe was constantly being pulled back to earth by the gravitational force of racism. Every step forward produces progress that generates a backlash.

We currently occupy one of those backlash moments. As I listen to Jefferson, Lincoln and King discussing Trumpworld, that is what I hear them talking about, in worrisome tones.

Joseph J. Ellis is an American historian who won the Pulitzer Prize for “Founding Brothers.” He is the author of the forthcoming “American Dialogue: The Founding Fathers and Us.”

Peniel Joseph: Radical citizenship is King’s lasting legacy

We too often posit Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, with its attendant outpouring of shock, grief and threats of racial war, as the beginning of the decline of the civil rights movements – as a major force for social change in American society. This is exactly wrong. More people demonstrated, organized, protested, voted and took to the streets in search of racial, political, social and economic justice in the 1970s than during King’s lifetime.

King’s greatest legacy stems from his willingness to speak courageous truths to powerful interests that made up American society. King denounced racial and economic injustice – whether they came from presidents, business leaders or clergy – as political and moral evils that disfigured American democracy and robbed the nation of its boundless potential.

King’s claim that young children risking physical assault and voluntary arrest in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 were carrying the nation back to “those great wells of democracy” resonated around the world as a transcendent message that made the particular struggle of black folk in America universal.

In so doing, King expansively redefined the very meaning of the term “citizen.” King’s visit to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles against the backdrop of the city’s urban rebellion, sparked less than a week after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, profoundly altered his understanding of citizenship.

After Watts, King came to realize that in addition to voting, true citizenship began with a good job, a living wage, decent housing, quality education, health care and nourishment. Full citizenship meant equitable treatment from all institutions in American society, most notably the justice system, local, state and federal governments, private businesses, churches and civic and secular organizations.

King worked toward this goal until the day he died in Memphis, a working-class, segregated city whose sanitation workers were engaged in a grueling strike for a living wage and safe working conditions. King’s time in Memphis with black garbage workers, alongside Mexican-Americans, poor whites and Native Americans, formed the core of his final crusade, a mission for economic justice that continued long past his death.

He reimagined America by placing racial justice at the core of our national values and conceptualizing a compassionate democracy capable of resisting the triple threat to humanity – militarism, racism, materialism – that he spent his final year railing against.

Remarkably, King’s dreams of a radical citizenship that allowed America to, in his inimitable words, “be true to what you said on paper,” resonates even more now than at the time of his death.

The litany of social movements for Black Lives, to end gun violence, eradicate sexism and misogyny, and protect the rights of immigrants and Muslims, all reflect King’s most revolutionary legacy: the realization that the myths of American exceptionalism needed to be replaced by what he called a “bitter and beautiful struggle” for the very soul of the nation.

That is to say citizenship meant, according to King, more than the absence of the negative structures of oppression he spent his life fighting. His greatest legacy is his demand for an active citizenship capable of guaranteeing justice for all.

Peniel Joseph is the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is also a professor of history. He is the author of several books, most recently “Stokely: A Life.”

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor: Nothing in the last 50 years has changed King’s calculus

Martin Luther King Jr. was a man disliked by a variety of people along the political spectrum when he died 50 years ago. His popularity began its precipitous decline after he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. King’s pivot from the battle to end Jim Crow and secure the right to vote for African-Americans in the South gave way to a much harder struggle to confront the depths of racism and discrimination that left black citizens in the worst jobs, housing and schools.

King’s battles in the South brought him into conflict with an array of powerful white racists, but the struggles against housing discrimination, school segregation and police brutality produced a different set of combatants, many of whom were protected by Democratic Party machines and black political operatives who acted as gatekeepers in black communities.

In King’s final months, he made preparations to organize a massive campaign of civil disobedience in Washington to bring attention to the persistence of poverty and to demand government action as a result. As King pointed out, “Our experience is that the federal government, and most especially Congress, never moves meaningfully against social ills until the nation is confronted directly and massively.”

King’s very public plans for “massive disruption” within the nation’s capital provoked the ire of both federal officials and liberals. Roy Wilkins, the national secretary of the NAACP, wrote an opinion piece for the Los Angeles Times criticizing King’s plans for civil disobedience as “not freedom of speech, but mafia-like dictatorship.”

King’s politics had moved further and further to the left as he confronted the recalcitrance of the federal government and as he connected the oppression and exploitation of ordinary people at home to the country’s war in Vietnam. The political conclusions reached by King during the liberal administration of Lyndon Johnson meant that the “racism, militarism and materialism” that lie at the core of the crisis in the United States was not simply a partisan issue. That these issues were systemic in nature led King to the conclusion that only a “radical reconstruction” of American society could solve them.

It was a position that earned him scorn across the narrow political spectrum of mainstream politics. But nothing in the intervening 50 years since his assassination has changed King’s calculus: both in the strategies he pursued and the political conclusions he reached.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor is an assistant professor at the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University. She is the author of “From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation” (Haymarket Books, 2016).

Jason Sokol: King knew when to break an unjust law

Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy of nonviolence and civil disobedience lives on today in those Americans who continue to practice civil disobedience in the face of injustice: the black athletes who have knelt peacefully during the National Anthem, the hundreds of thousands of youths who took to the streets in the March for Our Lives, and those in the Black Lives Matter movement who are waging nonviolent protests after the killing of Stephon Clark. King himself was often more disruptive and confrontational than these modern-day protesters have been.

King’s legacy also remains applicable for the untold numbers of immigrants who came to our land seeking a better life, and now seek only to keep their families together amid the increasing threat of deportations. In his 1963 “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” King declared: “Anyone who lives inside the United States can never be considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.” He went even further in a 1967 speech in New York calling for “a worldwide fellowship that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class and nation.”

In a recent dispute over “sanctuary” cities, Thomas Homan, the acting director of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, cited his agency’s devotion to “federal laws that ICE is sworn to uphold.” King heard the same arguments from law enforcement officials in the South, and he challenged them – day after day, year after year. When Southern officials brutalized and imprisoned African-American protesters, as Bull Connor, the segregationist public safety commissioner, did in Birmingham in 1963, they claimed that they were only upholding the law. King responded that these laws were unjust: “An unjust law is a code that a numerical or power majority group compels a minority group to obey but does not make binding on itself.” King explained that Americans had a duty to resist such laws. He repeatedly broke unjust laws himself and was often scorned as an agitator.

History has valorized King. In turn, those who zealously enforce the laws – without regard for whether those laws are just or humane – risk becoming known as the heirs to Bull Connor.

Jason Sokol is the Arthur K. Whitcomb Associate Professor of History at the University of New Hampshire. He is the author of “The Heavens Might Crack: The Death and Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr.” (Basic Books, 2018).

Steven Levingston: King was the rare man who could change a president

Decades ago, many African-Americans proudly displayed three portraits on a wall at home: Jesus, Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy. There was little question why Jesus or King had a place of prominence. But how Kennedy joined the wall of honor is a complicated story.

Kennedy has long been regarded as a champion of civil rights. It is true that he pushed forward the movement for black equality, but it is also true that his path was slow and hesitant. When he came into office in January 1961, Kennedy was not a strong civil rights advocate; he was more concerned about his political agenda than the struggles of 20 million black Americans. It took him 2? years to come around.

So, what changed him?

You could say he had a guiding spirit, an angel on his shoulder. The deeper you look into those 2? years, the more carefully you look, everywhere you look stands King: his preaching, his reasoning, his leadership and most important, his moral authority. King was instrumental in guiding Kennedy toward his awakening on civil rights – a transformation that was crucial to desegregation and the eventual passage of landmark civil rights legislation.

King challenged Kennedy, instructed him, urged him to think about the legacy of slavery and the meaning of inequality in America. Finally, after 2? years of bus burnings, beatings, children’s protests, riots and arrests, Kennedy had an epiphany and announced plans for civil rights legislation.

On June 11, 1963, the President told the nation: “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.” He spoke of black hardship in empathetic terms. “If an American, because his skin is dark … cannot enjoy the full and free life which all of us want, then who among us would be content to have the color if his skin changed and stand in this place?”

King never claimed credit, but it was he who showed Kennedy the path to his own conscience. What King taught Kennedy remains relevant today. In times of crisis, we need leaders who listen and learn and evolve in office, leaders who have courage, compassion and tolerance for all Americans. But as King observed in Look magazine in 1964: “It’s a difficult thing to teach a president.”

Steven Levingston, the nonfiction editor of The Washington Post, is author of “Kennedy and King: The President, Pastor, and the Battle Over Civil Rights” (Hachette Books).

Gilbert King: Both faith and strategy define King’s legacy

In May 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Tallahassee, Florida, to call attention to a little-known case that he hoped would shine a bright light on the inequalities of the criminal justice system.

Two weeks earlier, Betty Jean Owens, a 19-year-old coed at the historically black Florida A&M University, was abducted and raped at gunpoint by four white men. When deputies arrested the men, they laughed and joked their way to the police station, seemingly confident that the rape of a black woman wouldn’t land them in much trouble.

In Florida, rape was punishable by death unless a jury recommended mercy, but white men rarely faced charges for sexual assaults on black women. (Since 1924 the state had executed 37 black men convicted of raping white women.)

The students at Florida A&M had confidence of their own, encouraged by their victory in the Tallahassee bus boycott. They urged the nation to pay attention to the case, and their protests caught the attention of King, who praised the students for their demonstrations, which, he said, “awakened the nation.”

“If the court fails now Florida will be condemned in the eyes of the nation,” King said, citing the case as an opportunity for the South to prove that it didn’t adhere to a double standard of justice. “I don’t believe in capital punishment,” King added, calling simply for “punishment suited to the crime.”

King said he had two reasons for not calling for capital punishment. The first, he said, was because “it might be possible to reach the hearts and souls of some of the white people” who might view the executions as “payback for all of the injustices that have been heaped upon us.”

The second, he said, was less nuanced. “I sincerely believe that capital punishment is wrong.”

In June 1959, a jury of 12 white men found the defendants guilty with a recommendation of mercy, and the judge handed down life sentences. Blacks were grateful for the verdict, but many scoffed at the recommendation of mercy because the jury claimed they had found, according to a report in the Baltimore Afro-American, “no evidence of brutality” when Owens was raped seven times.

King believed it was wrong “to do the same thing to the white man that he has done to us over the years,” and that it was his “Christian ethic of love” that guided his dealings in racial inequalities and injustice. In doing so, King profoundly demonstrated not only the Christian beliefs that define his legacy but also a nuanced strategy regarding capital punishment and the pursuit of equal justice in the Jim Crow South

Gilbert King won a Pulitzer Prize for “Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America.” He is also the author of “Beneath a Ruthless Sun: A True Story of Violence, Race, and Justice Lost and Found” (Riverhead Books, 2018).

Eddie Chambers: How King’s life and death shaped the arts, then and now

The traumatic assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 was a pivotal moment in the manifestation of racial politics but also in the development of the arts in America.

In the wake of King’s murder, a significant number of traditionally conservative arts institutions immediately altered their programs to accommodate a variety of tributes. Perhaps one of the most significant was the Museum of Modern Art’s rapidly organized exhibition, “In Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King.”

Taking place just seven months after King’s murder, the New York exhibition consisted of works by many leading artists of the time, the sales of which benefited the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an African-American civil rights organization for which King served as its first president. It was the first time the museum held an exhibition to benefit another organization, and participants included legendary black artists such as Romare Bearden and Jacob Lawrence but also white artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Mark Rothko.

In responding to King’s assassination, white-controlled arts institutions in particular, from theaters to art galleries to museums, realized that their programs had to work harder to recognize the importance of diversity. Black playwrights such as Adrienne Kennedy, Ntozake Shange, Douglas Turner Ward, George C. Wolfe and August Wilson were able to have their work presented at theaters across the country. Of course, the range of African-American-led arts organizations across the country reacted to King’s murder with similar initiatives, pointing to the urgent need for a shared, cathartic response. While some may be exasperated by the inconsistency with which major arts organizations responded to the challenges of enacting diversity even to the present day, when we see African-American art(s) in the institutions around us, we can often trace such programming back to a 1968 moment.

The year that changed the world

Today, given the challenging nature of these times, some people feel nostalgic for the exigent messages conveyed by the art of the 1960s, most notably after King’s assassination. Several institutions recently hosted an exhibit, “Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties.” Taking its cue from the passing of the Civil Rights Act 50 years earlier, “Witness” struck a chord with gallery-going audiences and was widely celebrated in its reviews. The 1960s are, after all, remembered as a time of dramatic social, political and cultural upheaval across the country. Equally as important, the ’60s were a time in which many of the nation’s artists responded to the urgency of their times by making some of the most principled and engaging work of the modern and contemporary era.

It is, arguably, the duty of arts organizations to respond to seismic moments in our nation’s history, and it was King’s untimely passing 50 years ago that gave, within the arts, a pronounced fillip to manifestations of cultural diversity and the struggle for racial equality.

Eddie Chambers is a professor of art and art history at the University of Texas at Austin.

King’s activism was built for future generations

Bree Newsome: What’s old is new again

On this solemn occasion of reflection 50 years after King’s assassination, it’s most important to recognize that King’s mission of peace and justice was actively undermined by the FBI and others during his lifetime before he was killed by a sniper’s rifle. Too often in our modern day we see an ahistorical narrative being applied to the civil rights movement that imagines it as having ended in triumph, its primary objectives accomplished with the end of forced segregation and the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. But King himself made clear that the passage of these acts represented only part one of his mission. In fact, shortly after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Watts riots broke out in Los Angeles following an incident of police brutality.

And the Voting Rights Act of 1965 has not survived intact. It was gutted by the US Supreme Court in 2013, leading to ongoing legal battles in Southern states such as North Carolina, where Republican-controlled legislatures have sought new methods to suppress black voter participation. In 2015, instead of celebrating 50 years of the Voting Rights Acts, the nation was reeling from a series of police killings of unarmed black people, uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore and a white supremacist opening fire and killing nine people at a historically black church in South Carolina.

Like many in my generation, I was raised to view myself as inheriting rights and privileges for which the previous generations had struggled and sacrificed. The expectation that we should have equality and the realization that we still didn’t have it led to black millennials rising up in mass protest during the latter half of the Obama administration.

Access to public accommodations is the only civil rights issue of the 1960s for which we aren’t still actively organizing and protesting. Voting, education, police brutality, housing and wealth inequality remain central issues of modern civil rights and black liberation. Understanding that King’s mission was violently interrupted in 1968 is key to understanding where we find the nation in 2018: deeply divided along racial lines with great unrest, multiple social justice movements occurring and a government openly hostile to black protest. What’s old is new again.

Bree Newsome (@breenewsome) is an artist and human rights activist who drew national attention in 2015 when she climbed the flagpole in front of the South Carolina Capitol and lowered the Confederate battle flag.

Marc Morial: We are at a crossroads, but all roads lead to justice

As a child of civil rights activists who worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr., I remember my mother’s despair over King’s fatal shooting 50 years ago this week. But what influenced me even more was my father’s stalwart response to her despair: The movement will go on, he told me. It must.

As one of the civil rights leaders who has the honor of speaking at the official Day of Remembrance in Memphis this week, I can attest both to the achievements that have been reached since King’s murder and the failures to uphold his legacy.

When King went to Memphis in April 1968 to support the sanitation workers’ strike, President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty was only 4 years old, but King had already concluded the government’s approach was “piecemeal and pygmy.” King advocated for an aggressive approach to ending poverty, including a commitment to full employment, a guaranteed basic income and construction of affordable housing.

King’s Poor People’s Campaign floundered in the wake of his death, and Johnson’s War on Poverty seems to have become, in the hands of later presidents, a War on the Poor. Income inequality has skyrocketed since the 1970s, and the buying power of the minimum wage has sunk.

Now, a new generation of activists has revived King’s vision, and the Poor People’s Campaign, led by the Rev. William J. Barber, has begun a series of rallies and protests. Young people across the nation have risen up to protest gun violence – in a sense, echoing King’s condemnation of the Vietnam War.

Fifty years after King’s death, we may be at a crossroads, but to paraphrase a favorite line of his: I do believe all roads lead, eventually, to justice.

Marc Morial is the president of the National Urban League and the former mayor of New Orleans.

Carol M. Swain: Racial oppression is changing; we need new appreciation for King

Martin Luther King Jr. was the imperfect prophet who called upon our better angels. Using religion and philosophy, King appealed to American values and principles, while seeking to connect with like-minded people. He was the right man at the right time in history to change hearts and minds across America and the world.

Unfortunately, Generation Z (1995-2012) and some millennials (1980-1994) don’t appear to be much interested in learning about King, his tactics or his legacy.

In my conversations with black students, it sometimes seems as if King’s contributions are seen as something to be endured during Black History Month without practical relevance for today.

George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” We should not allow King’s legacy and the lessons he taught us to lie buried beneath mounds of grievances.

Blacks have achieved enormous success in many areas. Some of the problems that remain are related to social class and culture. Racial oppression is changing, bringing with it new victims, new forms of victimization and a lack of unifying, prophetic voices.

At this 50th anniversary of King’s assassination, we need to reflect on what we can do to instill a fresh appreciation of his vision in those who have not grasped the significance of his life.

Carol M. Swain is a former associate professor of politics at Princeton University and former professor of political science and law at Vanderbilt University. Her forthcoming book is “Debating Immigration: Second Edition” (Cambridge UP, July 2018). Facebook: Profcarolmswain. Twitter: @carolmswain

Tami Sawyer: King taught my generation not to ask for consensus but to make it ourselves

Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “A genuine leader is not a searcher of consensus, but a molder of consensus.”

In the beginning of 2017, Confederate statues in Memphis were not a major focus of anyone’s political agenda. By the end of that year, the statues of Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis were removed from their pedestals of prominence in our city’s public parks. Beginning in May, a movement, which I titled #takeemdown901 after a sister movement in New Orleans, began.

Throughout the year, #takeemdown901 received many criticisms. While the most obvious ones came from white supremacists and Confederate apologists, the more surprising one came from moderates who did not agree with our methods for change. Their advice to me and the members of #takeemdown901 was to be a bit quieter and have a lot more patience. Studying King, I knew that it was the methodology of the moderate to take more umbrage with the type of protest than the reason behind the protest. So we continued to push with fervor and urgency.

Knowing that the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination was approaching on April 4, 2018, #takeemdown901 set that day as the deadline for the removal of Memphis’ Confederate statues. King was assassinated less than five miles from both Confederate statues and their parks. It would have been extremely hypocritical for our city to launch a wide-scale commemoration for the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination and still allow the statues of slaveholders to stand in positions of honor. There were many who felt we didn’t take the right tenor with our boisterous social media outreach, protests, petitions and traditional media campaign, which called out our city and state for their complicity in the statues remaining. But when we stood outside Health Sciences Park on December 20 and watched the removal of the statue of Forrest, we knew we had made the good kind of trouble to achieve our end goal.

There are many systemic issues, such as extreme poverty and educational segregation, which are unacceptably the same in Memphis as they were in 1968. Promisingly, there is a growing movement of political and grass-roots leaders who are no longer seeking only a consensus. We are molding the consensus into the change we want to see in our city. Because we did not wait for approval of our methods, #takeemdown901 was able to ensure that the physical landscape of Memphis is different as we commemorate King’s legacy.

Policy and leadership in Memphis urgently require great change in the near future. I believe that this change will come from the consensus molders that we see stepping up in greater numbers to answer King’s call for the radical economic and political redistribution that is necessary for true equality.

Tami Sawyer is the director for diversity and cultural competence at Teach for America Memphis and a social justice advocate. Named by The Tennessean as one of 18 Tennesseans to watch in 2018, Sawyer founded #takeemdown901, the successful movement to remove Confederate statues in Memphis. She frequently speaks and writes about the continued movement for social justice and racial equity in the South. Sawyer is currently a candidate for Shelby County Commission.

Reginald Dwayne Betts: I’m not sure at all that I do King’s memory justice imagining that today’s civil rights issue is mass incarceration

My mother, barely a grade-school student in 1968, remembers Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. But I came up in a different era. By the time I’d reached middle school, King had become only a holiday. Streets and schools commemorated his life. And each year, though at some point during the month of February, a teacher would tell us that he led the Montgomery bus boycott, he was more myth than man. But what’s worse is that for me, born 12 years after King’s assassination, by the time I’d become a man, the issue confronting my peers and me had stopped being civil rights and had become keeping black and brown people out of prison.

A little over 10 years ago, one Sunday morning, I sat inside of a packed African Methodist Episcopal church just outside of the nation’s capital. Back then, I’d just begun dating my wife, and every moment of every day, it seemed, was about impressing this intelligent college student who had taken a chance on a guy who still carried the funk of jail cells in his pores. I’d read King’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” while incarcerated in a similar cell and that morning, I thought about how different it was to go to prison for robbing someone, as I had, than to go for marching.

The pastor asked for each man in the sanctuary 26 years old or better to stand up. I was a jail-weary 26 and stood with the sea of black men who rose, and if there was a sound we made it would have been thunder. You know the moment, when everyone feels like by standing they belong, that’s where we all were, feeling like we belonged. Then the pastor went on to explain that at 26, King led the bus boycott. And we all started wondering how we’d pilfered so much of the time we’d been given.

We’re 50 years after the assassination of King, and I’m not sure at all that I do his memory justice imagining that today’s civil rights issue is mass incarceration. So many of us, young and old men and women of color, have walked into jail cells and prisons with the memory of crimes we committed. I just don’t know how to juxtapose the fight to integrate the public school system with wanting parity in drug sentencing laws and police enforcement. Some days, I stare at my sons and wonder how we messed it all up, how we went from engaging in an irreproachable fight for justice to just wanting our crimes to count for less.

Reginald Dwayne Betts is a poet, memoirist and graduate of Yale Law School. He is an Emerson Fellow at New America, working on a book that examines the criminal justice system through his experience as a formerly incarcerated person working as a public defender.

N.K. Jemisin: I pray it won’t take another 50 years

In 1963, as Martin Luther King Jr. sat in solitary confinement in Birmingham, he lamented the failures of white moderates, who at the time seemed to prefer “a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

It must have seemed clear to King that even white people who claim to support equality are unreliable allies – willing to talk the talk and walk a few steps, but only if their own anxieties are put first.

Which is why the civil rights movement made what progress it did by effectively shaming white moderates into doing the right thing. This makes me wonder what America is to do in 2018, when our society daily endures a shameless embarrassment of a President, abetted by his shameless party and the shameless media – and when, too often, some white liberals and moderates openly wonder if there’s some way to ease tension between themselves and … fascists.

I have no solutions to offer, other than to survive and to try and help as many others survive as possible. It saddens me that we’ve progressed so little in the 50 years since King’s death. I pray it won’t take another 50 years for all of us to know the presence of justice at last.

N.K. Jemisin is an author of speculative fiction. In 2016, she became the first black to win the Hugo Award for best novel for “The Fifth Season.” In 2017, she won Hugo for best novel again, for “The Obelisk Gate.”

Kevin Powell: I still have faith because he had faith

I was born in the late 1960s and have no memory of Martin Luther King Jr. What I recall is being in kindergarten in the 1970s, at a predominantly black grade school, and our well-meaning teacher introducing us to King’s life in an animated film – and it ended with his death. That troubled me for years, and so did his final “Mountaintop” speech, the eeriness of it.

I thought of this last week as I visited the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where he was assassinated 50 years ago. I stood on the balcony outside Room 306 in the spot where he was struck by a single bullet. I cried and prayed for his soul, I cried and prayed for America’s soul. More than 1 million Americans have lost their lives to gun violence since King was killed. Yes, we have made some progress in America.

Because of King and the civil rights movement, a poor black boy – me – got to college, whereas my single mother has an eighth-grade education and my maternal grandmother could not read or write. But as long as there is racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, transphobia, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, a hatred of immigrants and a reckless disregard for the disabled, King’s “beloved community” remains but a dream deferred. I have faith, because he had faith. However, this anniversary of King’s death should not simply be a reflection but also a call to action that we must do better, Americans, human beings, for the sake of us all.

Kevin Powell, writer, activist, public speaker, is the author of 13 books, including his upcoming collection of essays about post-MLK America, “My Mother. Barack Obama. Donald Trump. And the Last Stand of the Angry White Man” (Atria Books/Simon & Schuster, September 2018). Follow him on Twitter @kevin_powell

Reshma Saujani: Our young people are the drivers of change

Earlier this year, Barack Obama reminded us all that Martin Luther King Jr. was only 26 when the Montgomery bus boycott began. He was 28 when he and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was only 17 when The Atlanta Constitution published his letter to the editor, “Kick Up Dust,” in support of equal rights.

As we commemorate and celebrate King’s legacy on the anniversary of his death, we should remember that our young people are drivers of change, that they are the ones who will set us free. They are leading movements against gun violence, sexual harassment, discrimination and more.

King would be proud of our kids. I know I am. I’ve seen, through Girls Who Code, what our kids are capable of achieving. They will create the world that King dreamed of, a world where we are judged not the by the color or our skin but by the content of our character.

Reshma Saujani is the founder and CEO of Girls Who Code.

Tess Taylor: I’m raising my son with King’s vision of hope, but also this reality

A few years ago, on a trip to visit family in Virginia, we passed through Appomattox. My 7-year-old son was 4 then, and it had been a busy trip, and since I hadn’t known we were planning to visit Civil War battlefields, I felt unprepared to brief him on the whole history of the war. I had not yet found words to talk about slavery or enslavement with my white child.

I was equally unprepared, when, storming the museum, perhaps in search of free screen time, my son made a beeline for the movie theater and arrived in the middle of the historic park’s documentary. He opened the door and slid in just moments before the sound of Lincoln being shot. Almost immediately, my son was in tears. Why would they do that? he asked. What was it really about? Those are questions we can spend lifetimes answering. I don’t remember the exact words I used, but I do remember telling my son that yes, that had happened, and yes, there is also a wider history of sadness and violence at the heart of our country. Yes, it did erupt then; yes, sometimes it still does erupt; no, that violence is not yet fully over; and yes, it is OK, and even necessary, that we allow ourselves time to grieve it.

On this 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death I find myself thinking about that summer visit to Appomattox again. This time I am preparing myself to talk actively with my son about both the importance of King’s work to our country, and planning some time to dwell in the troubling sadness of his too-early death. Taking this time feels like part of my responsibility as a parent. Talking about America’s painful racist legacy with our children is hard for all of us, and I am sure that as a white parent it is easier for me not to have to have conversations with my son about skin and skin color, about how race gets lived in America. But to me, talking about race – as it’s been lived in the past, as it gets lived in the present – is a critical part of helping my children understand our American journey – our aspirations, our shortcomings and the work we have ahead.

Now that my son is older, we’ve talked more explicitly about the strange paradox that we live in a country that was born celebrating ideas of freedom but also keeping other people from it. We’ve talked about living in a country that in its best incarnation dreams of fairness but does not deliver that fairness equally to all people. And we’ve talked about the amazing work of King in helping us dream and work toward a more just future.

I know that my son’s life will be one of expanding reckonings. My son’s grandfather’s great-grandfather enslaved humans; his grandfather grew up in segregated schools in the South. My parents and husband and I – all of whom are watching my son grow up – know full well that the work of changing that legacy is not yet finished. We know that we can’t turn away from our painful history but must work forward through it. We owe it to our children to help them understand the complex country they are inheriting.

King’s vision was ultimately one of hope – that one day we will reach a more perfect union together. I also want to honor that hope. I know that I deliver my son a beautiful and also deeply imperfect world, and I also hope that he’ll help be part of a generation that pushes our great American dream of living in justice further toward reality. “Not one piece of this is your fault, honey,” I have said to him, “but it is our responsibility to work to make better.”

Tess Taylor is the author of the poetry collections “Work & Days” and “The Forage House.”

In good times and bad, how to embody King’s legacy

Kristen Clarke: Today, the collective power of the vote still matters

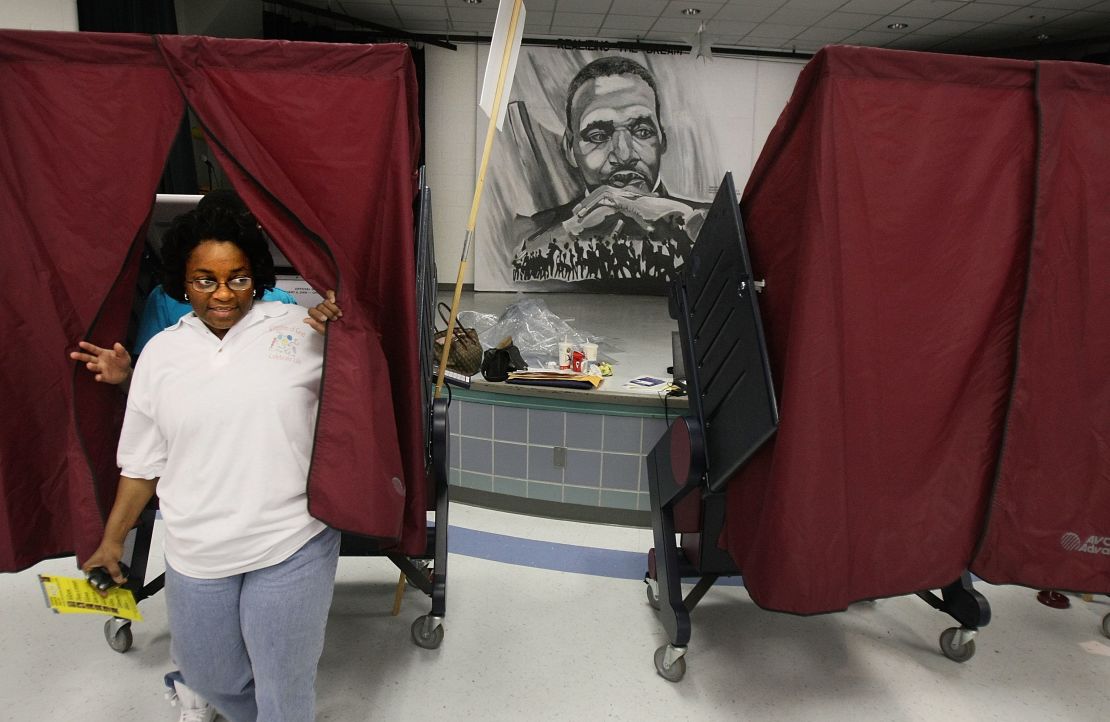

Martin Luther King Jr. fought many battles but his work to ensure access to the ballot box occupies a special place. On March 25, 1965, he led thousands of nonviolent demonstrators on a 54-mile march from Selma to the steps of the Alabama Capitol in Montgomery on a campaign for voting rights. A turning point in these efforts was Bloody Sunday, a day when state troopers unleashed dogs, billy clubs and tear gas on peaceful demonstrators in a gut-wrenching display of violence that was telecast on black-and-white TV screens across the globe.

Shortly after Bloody Sunday, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which led to progress in many places. But a 2013 Supreme Court ruling gutted a core provision of that law, fueling voter suppression efforts across the country. Today, efforts to restrict access to the ballot box are simply unrelenting and carried out, as the 4th US Circuit Court of Appeals aptly described, with “almost surgical precision” to impede the rights of minority voters.

My organization, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, remains engaged in a four-year battle with Texas over its restrictive and discriminatory voter ID law, one of the worst in the nation. We are fighting Alabama, a state that continues to elect judges at large to the state’s three highest courts, denying African-Americans a fair opportunity to elect judges of their choice through single member districts. And just last week, Georgia lawmakers brazenly attempted to cut early voting opportunities in Atlanta and on Sundays – a clear attempt to impair access for African-Americans in the city and for those who traditionally vote after church on Sundays. In states such as Florida, Tennessee and Kentucky, vast numbers of African-Americans remain disenfranchised by laws that strip away the right to vote from people with felony convictions.

In his speech, “Give Us the Ballot,” King talked about the transformative power of the vote. He saw the movement for voting rights as a way to bring lawmakers of goodwill to the table, as a way to confront white supremacy and a way to ensure the election of judges who could be fair and impartial. As of February, there are 63 restrictive bills that have been introduced or carried over in 24 states that all seek to make it harder for people to vote.

If he were alive today, King would be incensed by the old and familiar tactics used to suppress minority voting rights. He would have been deeply offended by this administration’s launch of the President’s Election Integrity Commission – an unprecedented attempt, despite its eventual failure, to lay the groundwork for promoting voter suppression policies across the country. He would also have expressed dissatisfaction with a Justice Department that is shifting course on voting rights. Today, civil rights lawyers and activists are engaged in a spirited struggle to safeguard access to the ballot box against ongoing threats. As new movements develop across our country to address gun violence, police brutality and women’s rights, the centrality of the right to vote remains undeniable. Just as King realized, one of the most important tools in the arsenal of social justice movements continues to be the collective power of the vote.

Kristen Clarke is president and executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a national organization founded in 1963 that works to address voting rights, education, fair housing and is working to end mass incarceration.

Cornell Brooks: Our lives, black lives and the life of King

Following Passover and Easter, people of all faiths are commemorating both the death and life of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as an apostle of nonviolence. It is precisely because King did not give up on nonviolence as both a practical strategy and principled philosophy that he became a target for an assassin’s bullet.

Fifty years after his assassination, we honor the legacy of King amid an American era of gun violence. And yet the words and work of King offer lessons today.

The story of King’s last days in Memphis of 1968 is an American story about violence – from beginning to end. The Memphis sanitation workers, without bargaining rights, were treated like human trash, working on a dangerous job at what King called “starvation wages.” These workers were subject to routine occupational violence; on February 1, 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed to death sitting on the back of a trash truck reeking with filth – as they sought refuge from the rain. Even, today solid waste workers still have one of the riskiest jobs in the country.

For King, initially Memphis was an unplanned diversion, not a planned destination. Not only did he go to Memphis to address the workers, he also promised to return to support them with a march. King subsequently led what was to be a peaceful on March 28, but things quickly disintegrated into window-breaking and a police response with mace, tear gas, batons and brutality. Dozens of people were injured, mostly black; a 16-year-old black child, Larry Payne, was shot to death. Hundreds were arrested, and National Guardsmen were mobilized.

King, forced to leave because of the violence, was blamed both for abandoning the march and the ineffectiveness of its intended nonviolence. Canceling a planned trip abroad, King again agreed to return to Memphis to persist in the nonviolent advocacy of workers’ rights.

King was shot on April 4, 1968, and this was followed by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. that June. King’s beloved mother, Alberta Williams King, was also shot to death six years after her son – as she was playing the organ in church. She was gunned down less than 100 yards from where her son was buried.

America marks the occasion of Martin Luther King’s death during an ongoing era of gun violence that only underscores how important his philosophy of nonviolence is today. America’s gun violence is embodied by both civilian mass shooters and police officers who have killed unarmed black and brown men, women and children (as well as some whites). Last year, according to data gathered by the Gun Violence Archive, 987 people were killed at the hands of the police, while there were 15,549 people killed by guns in the United States.

America’s gun violence problem is symbolized by both the March for Our Lives and the Movement for Black Lives. Student activists, whether they be from Parkland, Florida, or Ferguson, Missouri, city or suburb, are all young practitioners of democracy who deserve the same moral empathy and the same media attention. King did not teach us to empathize with the victims of violence by race, region or ZIP code.

King’s philosophy of nonviolence was based on the Imago Dei, namely that every person is created in the image of God and has inherent value. To honor King’s life on the anniversary of his death means we must value the beauty, dreams, hopes and humanity of all victims of gun violence. The innate worth of every person not only undergirds King’s philosophy of nonviolence and the insistence of the American Declaration of Independence that we all have God-given rights but also that black lives matter.

Cornell Brooks is a former president and CEO of the NAACP. He is visiting professor of ethics, law and justice movements at Boston University School of Law and School of Theology, senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice and a senior research scholar at Yale Law School.

William J. Barber: Nothing would be more tragic than to turn back now

Dorothy Day said, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” America would do well to recall her words as we honor her contemporary on this 50th anniversary of his martyrdom, for in celebrating him we risk missing his call to each of us.

It is too easy to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of black and white together but forgetting that the March on Washington was a call for jobs and economic justice. It is tempting to remember King’s last sermon in Memphis as only a bright and glorious vision from the mountaintop. A preacher in the prophetic tradition, King knew he could never proclaim hope without lifting people up. But to separate his word of inspiration from his prophetic instruction is to risk reducing him from prophet to motivational speaker.

Anyone who wants to honor King this week must go back to the beginning of his speech on April 3, 1968, at Mason Temple. There King stated his theme, a summation of what he had learned from 12 long years of fiery trial in the freedom movement: “Nothing would be more tragic than to turn back now.” After demonstrating the power of nonviolence to challenge Jim Crow in Montgomery, the movement had linked up with young people in the sit-ins and Freedom Rides to compel the federal government to uphold the 14th and 15th amendments through the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. But King always knew that reconstructing American democracy required both political and economic empowerment. The Poor People’s Campaign was about pressing on in truth and love to become the America we had never yet been.

Together with Ella Baker and Bayard Rustin, Fred Shuttlesworth and Fannie Lou Hamer, King experienced what the hymn says: “Just when I thought I was lost/my dungeon shook and my chains fell off.” Their movement was always up against great odds. But Gandhi had showed them the pattern: First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, and then you win. In a struggle for justice, resistance is your confirmation. The money, violence and lies waged against you are a measure of your power. Or, as they used to say in the South African struggle against apartheid, “Only a dying mule kicks the hardest.”

As unprecedented sums of money are poured into politics and voter suppression tactics proliferate, we need to hear King afresh: Nothing would be more tragic than to turn back now. Racism, poverty, ecological devastation, the war economy and a distorted moral narrative have intersected to undermined democracy over the past 50 years. Any of us who would honor King must resolve to go forward together, not one step back. We must reach down into the blood of the martyr, take up his baton and run the next mile of the way. In the face of extremism, people in 39 states and the District of Columbia are committed to 40 days of coordinated direct action this spring as part of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. We will be living King’s legacy in action.

The Rev. William J. Barber II is co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and President of Repairers of the Breach. He is author of “The Third Reconstruction.”

Amy Liu: King’s understanding of economic justice should shape the 21st century

I was born after key victories of the civil rights movement, such as the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. So when I visited the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis recently, I received a powerful re-education that left me with pride and shame at this period of our nation’s history. It was also hard to escape mirrors of today’s struggles – police brutality in cities, marches (in Charlottesville, Virginia, and elsewhere) that protest integration, and the slow cultural acceptance of equal rights and access. The museum tour ends at the room and balcony in which Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated 50 years ago, adding to the sense that the work to advance racial equality remains undone.

Today, the struggles continue. Too many people remain on the margins of a dynamic American economy. While black employment levels have improved, income and education disparities between black and white Americans remain stark. And if that isn’t somber enough, new research points to race as an even more powerful indicator than family wealth in explaining the divergent economic outcomes of black and white males. Meanwhile, many black Americans still live in racially segregated neighborhoods that are increasingly located far from centers of new job growth.

The failure to address de facto segregation is not simply bad for humanity, it’s also a major risk to American competitiveness. The strength of the modern economy depends on our collective ability to achieve innovation and inclusion in an era of rapid digitalization and demographic change. Yet, black and Hispanic workers are currently underrepresented in the fast-growing tech sector in nearly every metro area in the country, particularly in computer and math occupations, while a majority of Americans under the age of 18 will be nonwhite by the next presidential election.

Given these challenges, employers, business leaders and economic developers are finding their way in the 21st century to the table long ago set by social justice advocates, neighborhood activists and educators such as King. Their engagement is critical as they hire, make investments and influence the priorities shaping community life. Motivated not by compassion – although that is crucial – these relative newcomers are driven by the imperative to foster continuous invention, seize new market opportunities and stay globally competitive. And a growing number are realizing that an economy that excludes people and perpetuates inequalities carries deep market costs, resulting in billions in lost regional income, insufficient talent and entrepreneurs to fuel local industries, and outmigration of firms and people to other regions.

What’s encouraging is that across the country, from San Diego to Indianapolis, and Chicago to Minneapolis, business leaders are embracing inclusive economic growth, leading or convening diverse coalitions to advance regional priorities that help under-represented people gain relevant skills, start and grow new businesses, and afford homes in neighborhoods with good jobs and schools. These regional commitments are key to ensuring that American prosperity comes not from the fruits of the few but from the untapped potential of more people, more firms and more communities participating in economic success.

Just weeks before his death, at a rally for sanitation workers in Memphis, King recognized that the achievement of equal rights under the law had not resulted in economic equality when he exclaimed, “What does it profit a man to be able to eat an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?” Fifty years later, we still struggle to see economic inclusion as a shared value, rather than a program, that must permeate individual mindsets, organizational missions, broader collaborations and systemic reforms. But that is what’s required if the United States is to live up to its aspirations of being a place of widespread opportunity and cutting-edge innovation.

Amy Liu is a vice president at the Brookings Institution and director of its metropolitan policy program.

Gerard Robinson: The path to the mountaintop isn’t always straight

Fifty years ago, this week, America lost a prophetic voice to a gun shot in the city of Memphis.

And the lingering psychological wounds require our care and attention still today.

For some, there is temptation to claim that little progress has been made in 50 years since the assassination of King. For example, community responses to the police killings of young black men from Sacramento to Baton Rouge, Baltimore to Minneapolis in the past few years have been compared to the Klan’s Birmingham bombing that killed four little girls and the martyring of King in Memphis. The temptation is to suggest that, then as now, black lives still do not matter in America.

The presidential election of Richard Nixon in 1968 ushered in a “tough on crime” mantra that is consistent with the playbook President Donald Trump is using today.

On the education front, in a case argued just the day before MLK’s assassination, Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, the Supreme Court held that “freedom of choice” plans which failed to desegregate public education are inconsistent with Brown v. Board of Education.

Today, public or private “choice” programs are in place in more than 40 states at a time when white students are a minority, and the complexion of 50 million public school students is becoming browner and poorer.

And the beat goes on.

However, as we consider the meaning of our post-April 4, 1968 world, we must consider what America was like before MLK fell.

The notorious practices of red-lining and whites-only deed transfers begot systemic and legal discrimination and segregation in housing, creating black ghettoes and isolation. LBJ signed the Fair Housing Act later in 1968, outlawing those practices.

Blacks were also demonstrably poorer. In 1968, 35% of blacks lived in poverty. Although stubbornly and disproportionately high, black poverty has fallen by more than a third overall while today the poverty rates for married two-parent black families, the norm for black families in 1968, are only slightly above whites and in the single digits.

Average black earnings have risen by 43%, even faster than that of whites. High school graduation rates for blacks mirror white attainment, and college graduation rates have more than doubled.

In a survey conducted in the past few months by Gallup for my organization, blacks in “fragile communities” – that is high poverty with limited opportunities and social mobility – are more hopeful about the future, value college education more, and want to start their own businesses at higher rates than similarly situated whites.

But the “good news” is colored in America by persistent gaps between blacks and whites.

One distressing new study shows that for a black boy, born rich or upper middle class, staying there is harder than for his white counterpart. Reaching the rags-to-riches success of the American Dream is more nuanced than we know.

But one exemplar of the American Dream, Barack Obama, noted, “Progress isn’t always a straight line or a smooth path.” In terms of what King might say about the current state of black America, it is not as much a crooked path but what mountain climbers call a “false peak” – the point you realize that you must go back into the valley to reach our shared, final destination.

MLK’s last public speech sums it up well, “I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead…I just want to do God’s will…I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

In that Memphis speech, as King figures himself as Moses on the mountain, black America – really all people in America – should see themselves as Israelites in the desert – wandering but not lost.

Though a man of God, Martin was also a believer in our American scriptures: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Those laws and wisdom should guide our next steps as people of all races and faith traditions acknowledge both the growing pains and the possibilities that are endemic to our American republic. Only then can we go down into the valley and come out on top, together.

Gerard Robinson is the executive director of the Center for Advancing Opportunity, a research and education initiative created by a partnership with the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, the Charles Koch Foundation, and Koch Industries.

Nina Turner: King would want us to find our beautiful selves

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, and five decades after his death, we are still pondering what our country might look like were he alive today.

King fought for racial and economic injustice. During his time, society was largely divided along racial lines, when blacks and whites had separate lunch counters, and where other people of color were rarely acknowledged. Since the civil rights movement, there has been tremendous progress along racial lines, but sadly, we are falling short in other areas. While some barriers have been lowered, others have been erected.

In the 21st century, one of the biggest barriers to progress is idolizing political ideology. With each passing election cycle, political affiliation becomes a bigger identifier for American households. With each passing election, we appear to look less on what King described as the content of a person’s character and more on the “D” or “R” beside their names.

Rather than discovering the shared experiences that unite us, we obsess over the political labels that divide us. Rather than discovering our beautiful selves, we obsess over who’s in our camp and who’s outside of it.

This obsession with political affiliation has inspired a “win at all costs” mindset. Most of us can barely stand to be maligned in the comments section of news stories, or in social media threads, but King withstood so much more. He famously said, “Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that; hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that.” He withstood his share of hate, but he did not allow it to make him bitter nor did he allow it to alter what he envisioned as possible for the future.

I wonder what he would think of the cruel, politically motivated attacks that have become synonymous with campaigning in the 21st century.

We have hit a fault line in this country. We can’t get people to see our point of view by calling them names or insulting their intelligence. We can’t inspire people who think differently from us to open their minds, if we attack them.

If we refuse to recognize and respect someone else’s humanity – even in the thick of the fight – we will be consumed by the same hate and backwardness that King and those who strive to follow his example oppose. For instance, when high school students made the decision to sit in at a Woolworth counter in North Carolina, they knew they wouldn’t be greeted with “Do you take cream and sugar,” but rather with people yelling at them and beating them, but they remained seated, knowing they were really taking a stand for change. They did not return blow with blow. Even though fighting back would have been a natural physical response, they knew their cause required more.

Today, many of us not only refuse to withstand challenges, we turn into the same type of bullies we rail against.

It may be tempting to think that discovering our beautiful selves is about refraining from fiercely advocating for what we believe in. It’s not. It’s about following King’s example and operating from a place of radical love and a belief in our shared humanity

Nina Turner is a former Ohio state senator, president of Our Revolution and a founding fellow at the Sanders Institute.