Editor’s Note: Kara Alaimo, an assistant professor of public relations at Hofstra University, is the author of “Pitch, Tweet, or Engage on the Street: How to Practice Global Public Relations and Strategic Communication.” She was a spokeswoman for international affairs in the Treasury Department during the Obama administration. Follow her on Twitter @karaalaimo. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Facebook’s latest secrecy problem is not going to get a lot of “likes.”

On Friday, Facebook announced that it had banned Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm with ties to President Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign, from using the platform. According to Facebook, “in 2015, we learned that a psychology professor at the University of Cambridge named Dr. Aleksandr Kogan lied to us and violated our Platform Policies by passing data from an app that was using Facebook Login” to Cambridge Analytica and Christopher Wylie. Facebook says that about 270,000 people who downloaded Kogan’s app, called “thisisyourdigitallife,” gave permission for Kogan to access information about them, such as their locations and posts they liked – but Kogan violated the rules by sharing it. Kogan disputes Facebook’s claim that he lied about why he was collecting the data.

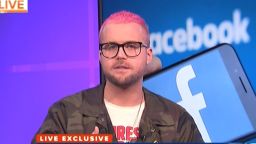

Wylie helped to found Cambridge Analytica but left in 2014, and now says the firm wrongly used the data to build psychological profiles of 50 million Americans for the Trump campaign.

“Cambridge Analytica will try to pick at whatever mental weakness or vulnerability that we think you have and try to warp your perception of what’s real around you,” Wylie said in an interview with ABC News. “If you are looking to create an information weapon, the battle space you operate in is social media. That is where the fight happens.”

Facebook says it thought the third parties with whom Kogan shared the data had deleted it in response to the social media company’s demands, but has now learned they didn’t. Cambridge Analytica said in a statement on Saturday that it deleted the data Kogan provided when it became clear that Kogan had not gathered it in line with Facebook’s terms of service.

Being profiled in this way by a political campaign is different than being targeted by a company selling shoes, for example, with a Facebook ad. While companies may select Facebook users based upon generic data such as what school they graduated from or what zip code they live in, industry practices prevent advertisers from knowing the personal identities of the people they’re targeting. Congress needs to respond now – in two ways.

First, we need laws that give Americans more information about how data we share online will be used. As I’ve argued before, organizations asking us to share personally identifiable information on social media should be required to say who they are, from whom they get funding, and how they’re going to use the data. This stipulation could help prevent situations like this in the future.

Second, Congress should force Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, to testify about what happened. This could shed some light on the shady way this all played out, helping lawmakers figure out how to prevent such episodes from recurring. It would also rightly publicly shame the company for failing to live up to moral obligations it had to its users to be forthcoming and transparent about what it knew.

It’s unconscionable that Facebook didn’t reveal what happened in 2015, when the company now says it first found out about it. Facebook had both legal and moral obligations to disclose all of this at that time. Although Facebook chose not to inform users in 2015, the company announced Monday that it had hired a digital forensic firm to conduct an audit of Cambridge Analytica’s servers and systems in an effort to show that it deleted certain data on some American users. A spokesperson for Cambridge Analytica did not immediately respond to a CNN request for comment about the audit.

The people whose data was shared without their permission had a right to know about it. Ann Ravel, an attorney who was previously chair of the Federal Election Commission, told me in an interview that the fact that Facebook didn’t disclose the problem earlier violates laws in most states requiring companies to notify people of such breaches.

Facebook also had a civic responsibility to tell Americans what was going on. The use of personally identifiable information (PII) in this way is widely eschewed by the advertising industry. The principles of the Digital Advertising Alliance – a non-profit group made up of industry organizations including the Better Business Bureau, 4A’s and Association of National Advertisers – require companies to “give clear, meaningful, and prominent notice” about how they collect and use data.

Clearly, the Americans who shared information about themselves on the “thisisyourdigitallife” app didn’t know it would end up in the hands of political consultants. If Facebook had disclosed before the 2016 election that a firm used by Trump was employing such dirty tactics, it likely could have changed the decisions of some voters at the ballot box.

On Monday, crisis expert Eric Dezenhall argued on CNBC that it’s unfair that Trump is being criticized for using social media in new ways, since President Obama did, too. That argument is ridiculous, of course, since the Obama campaign was never accused of using deceptive practices to obtain data. Obama was the first presidential candidate to fully exploit social media platforms to communicate with voters; Trump tweeted constantly on the campaign trail, but his team is now accused of using unethical and widely disavowed practices to obtain information about potential voters.

An earlier disclosure by Facebook could have also flagged possible violations of the law. Ravel noted that Federal Trade Commission rules state that “access to and disclosure of PII … must be strictly limited to individuals with an official need to know.” Furthermore, Cambridge Analytica is an affiliate of a British firm. Although Cambridge Analytica has not made a public statement about the audit or its international status, it’s not legal for foreigners to work on political campaigns in the United States.

A timely announcement by Facebook could have brought these issues to light – and could have influenced the decisions voters made on Election Day. While ads may promote products or even politicians based upon demographic information, it’s widely recognized that it’s not okay to use personally identifiable information about Americans without our permission. Disclosure of such dubious practices could have also sparked more timely action by regulators. Lawmakers need to prevent the company from getting away with such secrecy again. They should start by summoning Zuckerberg to Capitol Hill.