As tens of thousands of Americans die from prescription opioid overdoses each year, an exclusive analysis by CNN and researchers at Harvard University found that opioid manufacturers are paying physicians huge sums of money – and the more opioids a doctor prescribes, the more money he or she makes.

In 2014 and 2015, opioid manufacturers paid hundreds of doctors across the countrysix-figure sums for speaking, consulting and other services. Thousands of other doctors were paid over $25,000 during that time.

Physicians who prescribed particularly large amounts of the drugs were the most likely to get paid.

“This is the first time we’ve seen this, and it’s really important,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, a senior scientist at the Institute for Behavioral Health at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University, where he is co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative.

“It smells like doctors being bribed to sell narcotics, and that’s very disturbing,” said Kolodny, who is also the executive director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing.

The Harvard researchers said it’s not clear whether the payments encourage doctors to prescribe a company’s drug or whether pharmaceutical companies seek out and reward doctors who are already high prescribers.

“I don’t know if the money is causing the prescribing or the prescribing led to the money, but in either case, it’s potentially a vicious cycle. It’s cementing the idea for these physicians that prescribing this many opioids is creating value,” said Dr. Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

CNN spoke with two women who’ve struggled with opioidaddiction, and they described the sense of betrayal they felt when they learned that their doctors had received large sums of money from the manufacturers of the drugs that had created such havoc in their lives.

Carey Ballou said she trusted her doctor and figured that if he was prescribing opioids, it must be because they were the best option for her pain.

Then she learned that opioid manufacturers paid her doctor more than a million dollars over two years.

“Once I found out he was being paid, I thought, ‘was it really in my best interest, or was it in his best interest?’ ” she said.

To do the analysis, CNN – along with Barnett and Harvard’s Dr. Anupam Jena – examined two federal government databases. One tracks payments by drug companies to doctors, and the other tracks prescriptions that doctors write to Medicare recipients.

The CNN/Harvard analysis looked at 2014 and 2015, during which time more than 811,000 doctors wrote prescriptions to Medicare patients. Of those, nearly half wrote at least one prescription for opioids.

Fifty-four percent of those doctors – more than 200,000 physicians – received a payment from pharmaceutical companies that make opioids.

Doctors were more likely to get paid by drug companies if they prescribed a lot of opioids – and they were more likely to get paid a lot of money.

Among doctors in the top 25th percentile of opioid prescribers by volume, 72% received payments. Among those in the top fifth percentile, 84% received payments. Among the very biggest prescribers – those in the top 10th of 1% – 95% received payments.

On average, doctors whose opioid prescription volume ranked among the top 5% nationally received twice as much money from the opioid manufacturers, compared with doctors whose prescription volume was in the median. Doctors in the top 1% of opioid prescribers received on average four times as much money as the typical doctor. Doctors in the top 10th of 1%, on average, received nine times more money than the typical doctor.

“The correlation you found is very powerful,” said David Rothman, director of the Center on Medicine as a Profession at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “What’s amazing about the findings is not simply that money counts but that more money counts even more.”

Paying doctors for speaking, consulting and other services is legal. It’s defended as a way for experts in their fields to share important experience and information about medications, but it has long been a controversial practice.??

Pharmaceutical company payments to doctors are not unique to opioids. Drug companies pay doctors billions of dollars for various services. In 2015, 48% of physicians received some pharmaceutical payment.

It’s illegal, however, for doctors to prescribe the drug in exchange for kickback payments from a manufacturer.

Dr. Steven Stanos, president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, said he wasn’t surprised that doctors who frequently prescribe a drug are often chosen and paid to give speeches about the drug to other doctors.

“They know those medicines, and so they’re going to be more likely to prescribe those because they have a better understanding,” Stanos said, adding that some of the money paid to doctors may have been to teach other doctors about new “abuse-deterrent” opioid drugs.

Stanos’ group accepted nearly $1.2 million from five of the largest opioid manufacturers in the United States between 2012 and 2017, according to a recent report by the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.

Stanos said the money was used for various projects, including courses on safe opioid prescribing.

“I would obviously hope that a physician would not prescribe based on some type of kickback or anything like that, that they’d obviously be prescribing [in] the best interest of the patient,” he said.

But Dr. Daniel Carlat, former director of the Prescription Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts, said the CNN and Harvard findings are in line with other studies suggesting that money from drug companies does influence a doctor’s prescribing habits.

“It’s not proof positive, but it’s another very significant data point in the growing evidence base that marketing payments from drug companies are not good for medicine and not good for patient care,” said Carlat, a psychiatrist who blogs about conflicts of interest. “It makes me extremely concerned.”

Barnett, one of the Harvard researchers who worked with CNN, said pharmaceutical companies pay doctors for a reason.

“It’s not like they’re spending this money and just letting it go out into the ether,” he said. “They wouldn’t be spending this money if it weren’t effective.”

According to a statement by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, drug companies support mandatory and ongoing training for prescribers on the appropriate treatment of pain.

“PhRMA supports a number of policies to ensure patients’ legitimate medical needs are met, while establishing safeguards that prevent overprescribing,” according to the statement from the group.

‘I trusted my doctor’

Angela Cantone says she wishes she had known that opioid manufacturers were paying her doctor hundreds of thousands of dollars; it might have prompted her to question his judgment.

She says Dr. Aathirayen Thiyagarajah, a pain specialist in Greenville, South Carolina, prescribed her an opioid called Subsys for abdominal pain from Crohn’s disease for nearly 2? years, from March 2013 through July 2015.

Subsys is an ultrapowerful form of fentanyl, which is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“He said it would do wonders for me, and it was really simple and easy. You just spray it in your mouth,” Cantone said.

She says Subsys helped her pain, but it left her in “a zombie-like” state. She couldn’t be left alone with her three young children, two of whom have autism and other special needs.

“I blacked out all the time. I’d find myself on the kitchen floor or the front lawn,” she said.

She says that if she missed even one day of the drug, she had uncontrollable diarrhea and vomiting.

She said she brought her concerns to Thiyagarajah, but he assured her it couldn’t be the Subsys that was causing her health problems.

“I trusted him. I trusted my doctor as you trust the police officer that’s directing traffic when the light is out,” she said.

She says that when she eventually asked Thiyagarajah to switch her to a non-opioid medication, he became belligerent.

“He said it was Subsys or nothing,” she said.

Cantone would later learn that from August 2013 through December 2016, the company that makes Subsys paid Thiyagarajah more than $200,000, according to Open Payments, the federal government database that tracks payments from pharmaceutical companies to doctors.

CNN compared the $190,000 he received from 2014 to 2015 with other prescribers nationwide in the same medical specialty and found that he received magnitudes more than the average for his peers.

Nearly all of the payments were for fees for speaking, training, education and consulting.

Cantone is now suing Thiyagarajah, accusing him of setting out to “defraud and deceive” her for “the sole purpose of increasing prescriptions, sales, and consumption of Subsys to increase … profits.”

Through his attorney, Thiyagarajah denied any wrongdoing but declined to comment on this story due to the pending litigation.

In a court filing responding to Cantone’s lawsuit, Thiyagarajah denied all of the allegations against him and said that all medical care provided to Cantone was “reasonable and appropriate and in keeping with the standard of care.”

His attorney, E. Brown Parkinson, said the doctor is currently practicing medicine, alternating weeks between his practices in South Carolina and New York.

Thiyagarajah might be expected to write a relatively high number of prescriptions for opioid painkillers, given that he’s board-certified in physical medicine and rehabilitation with a subspecialty in pain medicine.

But he wrote an unusually high number of prescriptions for Subsys and other opioids even when compared with other doctors with the same certifications.

In 2014 and 2015, physicians with Thiyagarajah’s certifications wrote an average of 3.7 opioid prescriptions per Medicare patient per year, according to the analysis by CNN and Harvard. Thiyagarajah, however, annually wrote more than seven opioid prescriptions per patient per year.

After about two years on Subsys, Cantone says, she took herself off the drug cold turkey.

According to an affidavit by an investigator for the Drug Enforcement Administration, Thiyagarajah’s office was inspected by the agency in June 2015 and found to be prescribing another opioid, buprenorphine, “for non-legitimate medical need” in violation of federal law.

In March 2016, the agent conducted another inspection and seized 45 medical records related to Subsys.

The DEA did a compliance review and referred its findings to the Department of Health and Human Services, according to Robert Murphy, associate special agent in charge of the agency’s Atlanta Field Division.

Cantone is also suing Insys, the company that makes Subsys. Insys denied allegations of wrongdoing in a court filing responding to Cantone’s lawsuit.

Separate from Cantone’s lawsuit, John Kapoor, the founder and largest shareholder of Insys, was arrested and arraigned in federal court in October on charges of bribing doctors to overprescribe the drug.

“Dr. Kapoor engaged in no wrongdoing and refutes all of the charges in the strongest possible terms,” said Tom Becker, a spokesman for Kapoor. “He looks forward to being fully vindicated after having his day in court.”

Kapoor resigned from the Insys board of directors in October, according to a company news release.

Several other Insys executives were arrested in connection with an alleged racketeering scheme.

Separately, Sen. Claire McCaskill, a Democrat from Missouri, is conducting an investigation into the opioid industry.

According to her investigation and the federal indictment, Insys used a combination of tactics, such as falsifying medical records, misleading insurance companies and providing kickbacks to doctors in league with the company.

Saeed Motahari, president and CEO of Insys, wrote a letter in September to McCaskill, noting that he was “concerned about certain mistakes and unacceptable actions of former Insys employees.” He added that most of the field-based sales staff were no longer with the company.

“I stand with you and share the desire to address the serious national challenge related to the misuse and abuse of opioids that has led to addiction and unnecessary deaths and has caused so much pain to families and communities around the country,” Motahari added.

The analysis

Sometimes, pharmaceutical companies pay doctors to do medical research. They also pay doctors for promotional work: for example, to speak with other doctors about the benefits of a drug.

Among the doctors who prescribe the highest volume of opioids, the CNN/Harvard analysis found that the largest amount of money was paid for that second category, which includes speaking fees, consulting, travel and food.

Concerns about payments to doctors by opioid manufacturers were brought to light last year in a study by researchers at Boston University.

Several studies published in medical journals in recent years have found an association between payments by pharmaceutical companies for various types of drugs and doctors’ prescribing habits.

For example, researchers at the University of North Carolina examined the two government databases analyzed by CNN and Harvard and found that when doctors received payments from manufacturers of certain cancer drugs, they were more likely to prescribe those drugs to their patients.

“This study suggests that conflicts of interest with the pharmaceutical industry may influence oncologists in high-stakes treatment decisions for patients with cancer,” the authors concluded.

Some studies have looked at whether the amount of money a doctor receives makes a difference. Studies by researchers at Yale University, the George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health and Harvard Medical School have all found that the more money physicians are paid by pharmaceutical companies, the more likely they are to prescribe certain drugs.

Dr. Patrice Harris, a spokeswoman for the American Medical Association, said that the CNN and Harvard data raised “fair questions” but that such analyses show only an association between payments and prescribing habits and don’t prove that one causes the other.

It’s “not a cause and effect relationship,” said Harris, chairwoman of the association’s opioid task force, adding that more research should be done on the relationship between payments and prescriptions.

“[We] strongly oppose inappropriate, unethical interactions between physicians and industry,” she added. “But we know that not all interactions are unethical or inappropriate.” ?

Harris added that relationships between doctors and industry are ethical and appropriate if they “can help drive innovation in patient care and provide significant resources for professional medical education that ultimately benefits patients.”

Stanos, the pain physician, said a doctor who gets paid by a pharmaceutical company and prescribes that company’s drug might truly and legitimately believe that the drug is the best option for the patient.

“I hope physicians that do promotional talks prescribe because they think the medicine has a benefit,” he said.

But Jena, one of the two Harvard researchers who collaborated on the CNN analysis, said he worries that money from opioid manufacturers – especially large amounts of money – could influence a doctor to prescribe opioids over less dangerous options.

“Every decision, every recommendation a physician makes, should be in the best interest of the patient and not a combination of the patient’s interest and the financial interest of the doctor,” said Jena, associate professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

“If we lived in a different world where none of these payments to physicians occurred, how many fewer Americans would have [been prescribed] opioids, and how many fewer deaths would have occurred?” he asked.

From 1999 to 2015, more than 183,000 people in the United States died from overdoses related to prescription opioids, according to the CDC. In October, President Donald Trump declared the opioid epidemic a national public health emergency.

At least one company has decided to stop paying doctors for promotional activities such as speaking engagements.

Purdue Pharma discontinued its speakers program for the opioids OxyContin and Butrans at the end of 2016 and the program for Hysingla, another opioid, in November, according to company spokesman Robert Josephson.

“We have restructured and significantly reduced our commercial operation and will no longer be promoting opioids to prescribers,” a company statement said.

More than $1 million in three years

Though Thiyagarajah’s opioid prescription rates were particularly high, many other doctors who have prescribed large amounts of opioids have also been paid large amounts of money by pharmaceutical companies that make the drugs.

Several patients have filed lawsuits against these high prescribers.

From August 2013 through December 2016, Dr. Steven Simon of Overland Park, Kansas, was paid nearly $1.1 million by companies that make opioid painkillers, according to the federal Open Payments database.

Most of the payments were fees for speaking, training and education.

Ballou, one of his patients, says she remembers Simon bragging about how drug companies were flying him across the country to give lectures to other doctors.

“He said he was going to Miami, and they were going to give him a convertible, and he was going to stay in the best hotel and eat the best Cuban food he’d ever had,” said Ballou, who filed a lawsuit against Simon after she says she became addicted to opioids.

Simon’s lawyer, James Wyrsch, said he would not comment on pending litigation.

In court documents, he asked for the case to be dismissed, saying in part that Ballou’s complaints that Simon improperly prescribed Subsys were “simply incorrect.”

Bridget Patton, a spokeswoman for the FBI’s Kansas City field office, said federal agents went to the office where Simon works, Mid-America PolyClinic, in July.

The clinic said in a statement that it is “fully and willingly cooperating with all investigations” and that Simon has not been employed there since July 24.

“We had a lawful presence at that facility,” Patton said. She declined to say whether investigating Simon himself was the purpose of the FBI visit.

The owner of the pain clinic, Dr. Srinivas Nalamachu, told The Kansas City Star that the agents showed up with a search warrant for Simon’s medical records involving fentanyl prescriptions.

Simon and his lawyer told CNN they couldn’t comment due to the pending litigation.

Ballou said that when she was Simon’s patient, it didn’t give her pause that the same doctor who was prescribing opioids to her was also taking money from the companies that made the drugs.

But now she looks back with anger.

Cantone, the patient who went to Thiyagarajah, the pain specialist in South Carolina, looks back with sadness.

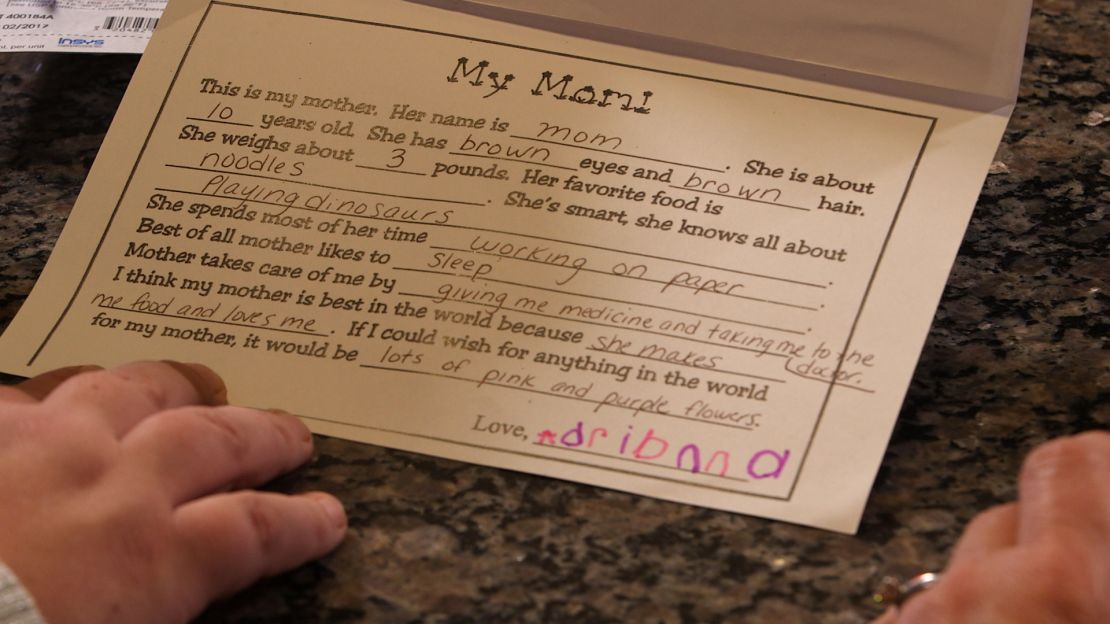

She cries as she remembers the Mother’s Day card her daughter made her in preschool. The teacher asked each child what their mother liked to do and wrote it on the card.

Her card said her mother liked to sleep.

“Instead of saying ‘she gives me hugs and kisses or takes me to the park,’ it was the years of her finding me on the floor,” Cantone said. “I feel like I failed as a parent.”

She becomes angry when she thinks about the hundreds of thousands of dollars her doctor was paid by the drug company.

“The medication that was being prescribed to me was for his benefit, not my own,” she said.

CNN’s John Bonifield contributed to this story. Janette Gagnon contributed research and David Heath contributed data analysis.