Story highlights

Filipino house maid tells of exploitation in Jordan

There are at least 50,000 migrant domestic workers in the country

Isa Al-Maeda says her life as a farmer in the Philippines was hard, but they were good days, surrounded by her siblings and parents.

She wanted to help support her family, which struggled to make ends meet, so in 2006 she took a job as a domestic worker in Jordan. She says she was promised $500 a month, which would have greatly helped her ailing parents.

Al-Maeda’s recruitment agency got her a job with a Jordanian family living in a town near the Syrian border. She was kept busy with the house chores, most of the time working 17 hours a day. The first month she received the $500, the following two she got $300; then the money stopped.

The family told her they were going through financial troubles and would pay her as soon as they got money, she says. They never did.

Read: Migrants tell of brutality in Libya

Al-Maeda says she could not leave because she was too scared to go outside, she didn’t know the country and didn’t know if anyone would help her.

It took her nine years to gather the courage to escape, something that was made harder after her residency and work permits expired and years’ worth of fines accumulated, which made her illegal.

Now 36 years old, Al-Maeda told CNN she understands she was a slave. Wiping tears from her eyes, she says what she has been through haunts her even in her sleep. The thought of wanting to send money to her family, but having nothing, has been the hardest thing.

Deceived by employers

Hers is not an isolated case. Rights groups have documented many cases where migrant workers are not paid on time; some are deceived by employers who promise to pay them at the end of a contracted period, but fail to do so. Some employers lock their workers in the home, forcing them to work up to 20 hours a day, seven days a week.

Withholding passports and restricting movement are also common, according to advocacy groups.

Read: The sex trafficking trail from Nigeria to Europe

According to official government figures, there are more than 50,000 migrant domestic workers in Jordan and another estimated 20,000 operating without proper documentation.

Most of the women come from South and Southeast Asia, and East Africa. Monthly salaries range from about $200 to $500 and many are expected to do everything from cleaning to cooking, ironing to gardening and childcare.

‘We try to let them feel that they are safe’

Linda Al-Kalash established the NGO Tamkeen in 2007 to provide legal aid to migrant workers. With her team of lawyers Al-Kalash took employers to court for labor violations and mistreatment of workers, winning several high profile cases.

“Through our experience and meeting with the workers themselves … they feel they don’t have any access to redress,” she said.

“Some of them are difficult to talk to, because they are afraid, they don’t have any trust in anybody. We try to let them feel that they are safe. It is very important to shake hands with them, to hug them sometimes, to let them feel that you and they are in an equal situation.”

In 2010 Al-Kalash received the US State Department Trafficking in Persons Hero award for her efforts to combat modern day slavery in Jordan.

She now works closely with government agencies, including the country’s Anti-Human Trafficking department, which has been credited with investigating hundreds of cases since it was established in 2013.

The Jordanian government acknowledges that there is a problem when it comes to migrant domestic workers, but officials say it is only individual cases, not a widespread issue.

Shelter for victims

According to the 2017 State Department Trafficking in Persons report, Jordan remains a “Tier 2” country – as it does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking, but is making significant efforts to do so.

In addition to creating the unit, the government opened “Dar Karama,” a shelter for human trafficking victims, where domestic workers are given refuge while their cases are investigated.

Suzan Koshbay, who heads the Ministry of Social Development’s Anti-Human Trafficking department, told CNN: “Dar Karama is considered the first step in the response to victims of human trafficking.

“It provides them with a safe space, with all the support services … that enable them to begin psychological and physical rehabilitation, and that enable them to acquire skills to lift their feeling of self-value and stop them from becoming victims of human trafficking again.”

According to Al-Kalash, Jordan is considered to have some of the best legislation in the Middle East when it comes to migrant workers. In recent years Jordan passed laws that would protect the rights of migrant workers, like limiting working hours and fining employers for withholding travel documents.

But these laws remain hard to enforce as not all workers come forward with complaints.

Jordan is also working on amendments to its anti-human trafficking law and the penal code to strengthen sentences for human trafficking violations.

In November 2017, Al-Maeda was deported back to the Philippines. Tamkeen is still handling her case, which could take years in the Jordanian courts.

Al-Kalash says she will never stop fighting for the rights of migrant workers, trying to improve their situation one case at a time.

“My message to them is, ask for your rights, don’t be afraid,” she said. “Go to a police station, go to the Ministry of Labor, file a complaint against your employer. You have the right … it is very important to empower yourself.”

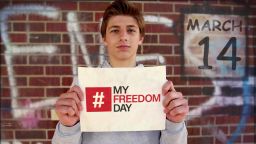

Join the CNN Freedom Project on March 14, 2018 for #MyFreedomDay – when students around the world will be holding events to raise awareness of modern slavery. Find out more at cnn.com/myfreedom