Story highlights

At least four medical groups call hate crimes a public health concern

Doctors and public health leaders weigh in on how racism and hate crimes hurt public health

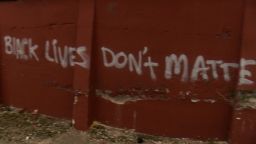

As a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, turned deadly on Saturday, doctors and public health leaders were among those watching events unfold on their television screens and social media.

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, was at a car dealership getting his vehicle inspected when he saw news reports of a car plowing into a group of counterprotesters. “I was horrified,” he said.

Dr. Elizabeth Samuels, an emergency physician in New Haven, Connecticut, and Providence, Rhode Island, was closely following the events in Charlottesville from home.

“I had actually been following the news, went out for a run and saw (counterprotester) Heather (Heyer) had been killed when I got back home,” she said.

Dr. Jack Ende, president of the American College of Physicians and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, also was watching from home.

“I was shocked to see what was going on,” he said. “I was shocked and saddened.”

Benjamin, Samuels and Ende all agree that the expressions of hate seen in Charlottesville over the weekend were a public health problem.

‘This is a public health issue’

Hate crimes directed at people based on their race, ethnicity, gender, nationality, sexual orientation, religion or other characteristics are a public health issue, according to a policy statement from the American College of Physicians that was posted on its website Monday.

“Is it appropriate for a medical organization to take a stance on hate crimes? The American College of Physicians said, ‘Yes, it was,’ ” Ende said.

“There are data indicating the public health ramifications of both the hate crime itself but also of the stigma of bias, the stigma of prejudice and hatred directed against somebody because of their sexual orientation, because of their race, because of their ethnicity or their country of origin,” he said. “For that reason, we felt that this is a public health issue, and we joined with other medical organizations to take a stance against hate crimes.”

The American Psychological Association, the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians also have issued policy statements on hate crime as a public health concern.

The American Public Health Association has a site devoted to racism’s negative impact on public health and launched a national campaign against racism, including hate crimes.

“We studied the statements of our sister groups before we came out with our own,” Ende said. “There is a consensus within the medical societies that this really needs to be kept on our radar.”

The American College of Physicians’ statement, which its board of regents approved last month, calls for more research on the impact of hate crimes, the understanding and prevention of hate crimes and interventions to address the needs of hate crime survivors and their communities.

“By identifying discrimination and hate crimes as public health issues, the ACP not only acknowledges the impact these factors have on our patients but also our role and responsibility to address them as part of our professional dedication to the health of our patients and the public,” said Samuels, who was not involved in the policy statement but attended a vigil in Providence on Sunday where people reflected on the violence.

“When I have cared for patients assaulted because of their race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age or disability, what has stood out to me is not so much the physical injuries inflicted – which are not to be minimized – but the psychological harm,” she said. “Hate-based violence and systemic racism are detrimental to public health.”

How hate hurts public health

Several studies suggest that experiences of racism or discrimination raise the risk of emotional and physical health problems, including depression, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and even death.

A study of 1,016 Arab-Americans found that their reports of abuse and discrimination after September 11, 2001, were associated with higher levels of distress, lower levels of happiness and worse overall health. The study was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2010.

As for hate crimes in particular, a study found that lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender high school students living in neighborhoods with higher rates of LGBT assault hate crimes were significantly more likely to report having suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts than students in neighborhoods with lower rates of hate crime. That study was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2014.

“Bottom line is that hate has physical and mental health consequences and should be considered within the remit of public health,” said Dr. Sandro Galea, dean and professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, who was not involved in the American College of Physicians’ latest policy statement.

In other words, being considered within the remit of public health means that hate crimes have significant public health consequences, such as being associated with mental and physical problems.

Galea said that he agreed with the policy statement, adding that what appears to be a recent rise in divisive language and outward expressions of hate is “deeply troubling” both as a citizen and as a doctor. He pointed to the weekend’s rally in Charlottesville as an example of that expression of hate.

“The escalation to outright violence, including the killing of one person, are the tip of the iceberg, the ultimate manifestation of the consequences of hate,” Galea said.

The American College of Physicians is not the first health organization to recognize hate crimes as a public health concern – and Charlottesville certainly is not the first city to see hateful rhetoric sweep its streets. Nor will it bethe last, with rallies planned in other cities this weekend.

America’s narrative includes not only the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the first federal statute to recognize hate crimes, but a haunting history of violent Ku Klux Klan gatherings and lynch mobs.

As for why the American College of Physicians and other health organizations are only now recognizing hate crimes as a public health issue, Ende said the health community has evolved and become more “sophisticated in our sensitivity” to determinants of illness and social issues.

Now, some medical groups are seeking out public health solutions.

‘We have the capacity as a nation to … fix this’

The American Academy of Family Physicians points to educational programs directed at the prevention of hate crimes as a possible solution, and such programs could be implemented in community centers and schools.

The American Psychological Association cites research suggesting that getting people from conflicting groups in the same room in a peaceful way to hear each other’s perspectives, such as in a town hall meeting, or teaching the history of hate in America – such as how there was prejudice against German culture during World War I – are both approaches to turning bias around and possibly preventing hate.

The American Medical Association even urges the expedient passage of appropriate hate crimes legislation.

The American Public Health Association’s campaign against racism includes three potential public health solutions to hate crimes and racism, Benjamin said. They mostly focus on public discussions.

“The first one is naming it. Identifying it. That is a very, very important first step, you know, putting it on the agenda,” Benjamin said.

In other words, he said, calling out a hate crime or racism by name can initiate public discussions. Then, as part of that discussion, the second step would be to identify how racism is driving policies, practices or social norms, he said.

For instance, “when you have two societies that live on different sides of the railroad tracks and there’s differences in their economic well-being and health … was that constructed?” Benjamin asked.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

The third step would be taking action, such as promoting or facilitating research and interventions through educational programs or community forums, to address racism and hate crimes from a public health perspective.

“The public health community is good at understanding the data, thinking about the population-based impact of it and then working with others, because we don’t do this alone. We work across many sectors to find solutions,” Benjamin said.

“I think we need to recognize Charlottesville is an overt expression of something that has been going on for a long time in our country,” he said. “That is a stain and a terrible, terrible situation in our country that we have to fix, and we need to do it now. We have the capacity as a nation to come together and fix this.”