Story highlights

Suicides among US children ages 5-12 are rare compared to other age groups

Study: Some factors in these suicides might differ from older children

One day after school in January, 8-year-old Gabriel Taye returned to his Cincinnati home and hanged himself with a necktie, his family’s attorney says.

His mother, Cornelia Reynolds, found his body that afternoon in his bedroom. His family sued his school district last week, alleging that he’d been bullied and that the school didn’t inform his relatives.

“Gabriel was a shining light to everyone who knew and loved him,” his mother said in prepared statement released to the news media. “We miss him desperately and suffer every day.”

Suicides among US children under 13 are rare, but perhaps more frequent than you think. And 8 is hardly the youngest.

More than 1,300 dead since 1999

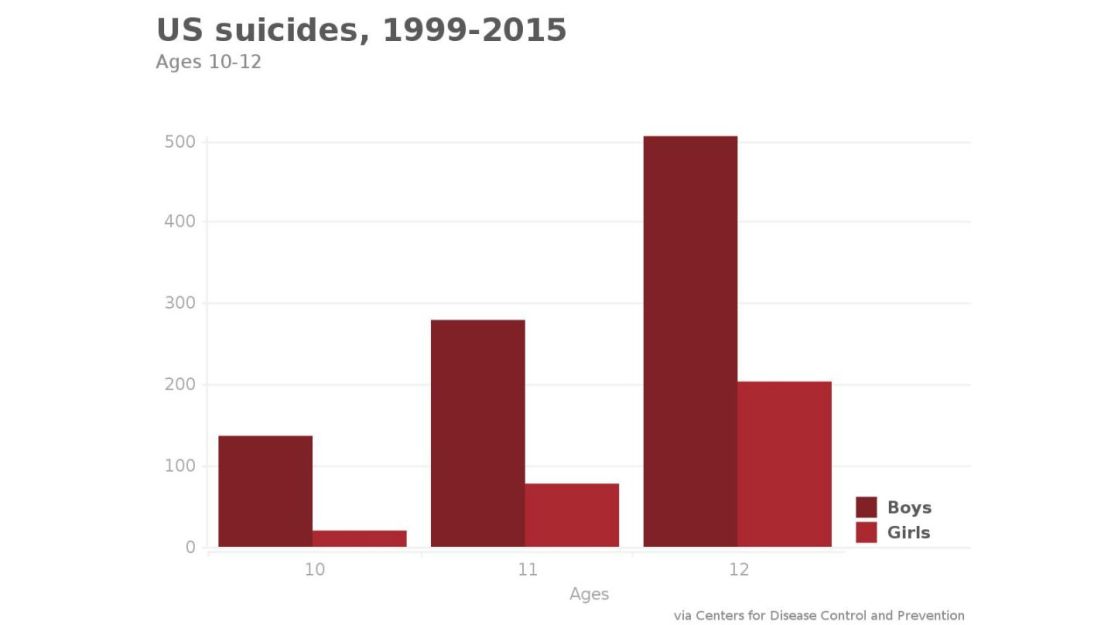

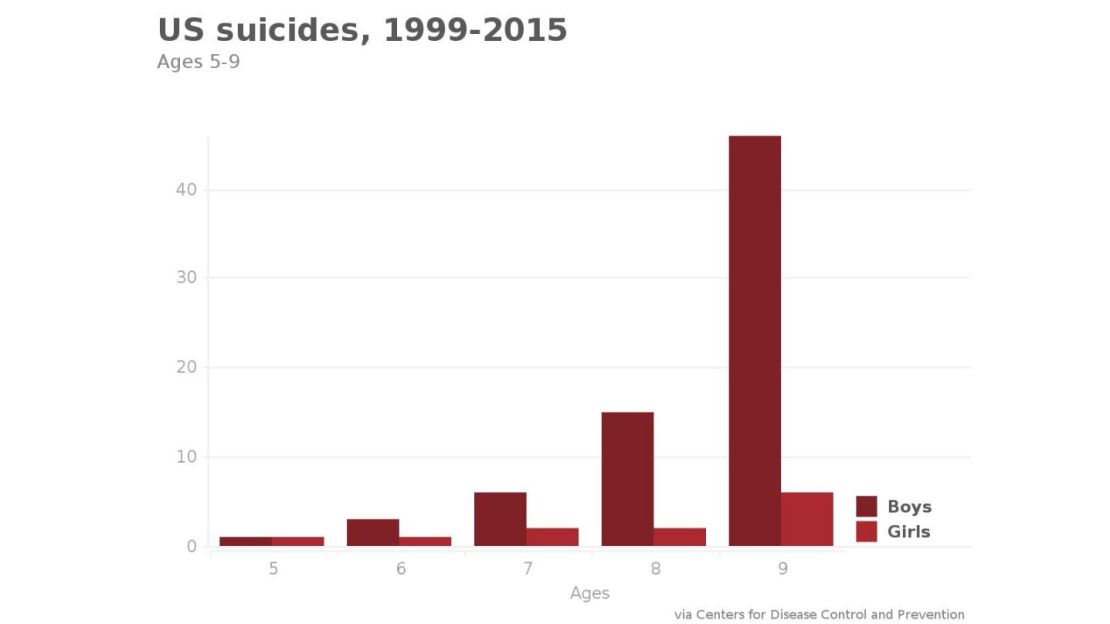

From 1999 through 2015, 1,309 children ages 5 to 12 took their own lives in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

That means one child under 13 died of suicide nearly every five days, on average, over those 17 years.

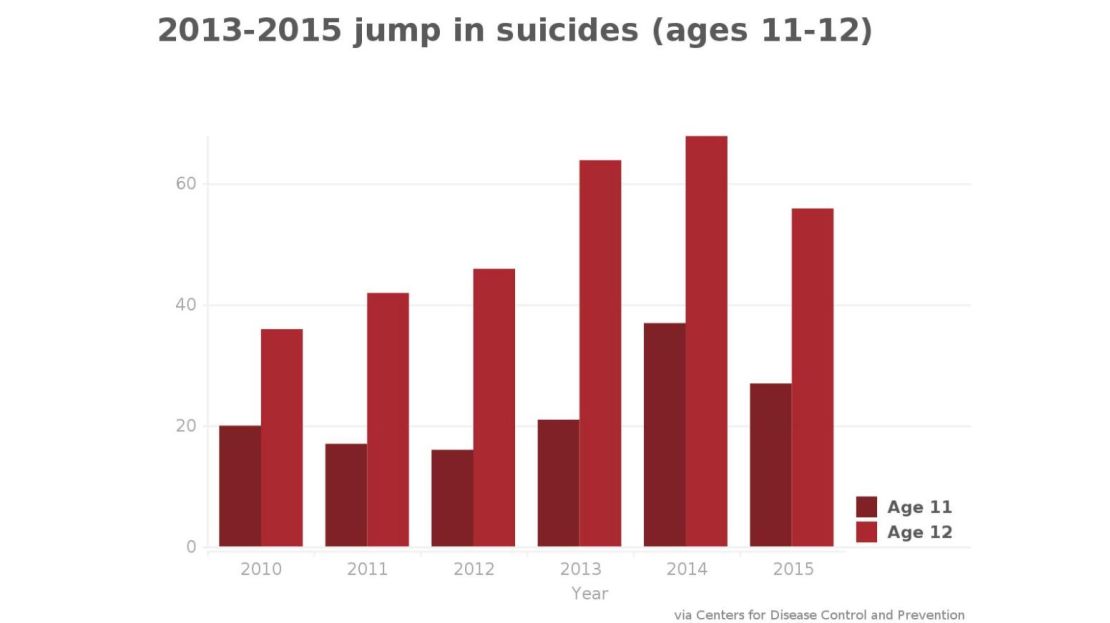

The frequency was higher from 2013 to 2015 – once every 3.4 days – thanks mostly to a 54% spike in the suicides of 11- and 12-year-olds compared to the three years prior. That jibes with the CDC’s announcement of a recent rise in suicide rates in ages 10-14.

Still, some perspective: Suicides before the teen years are infrequent compared to other groups.

There were 0.31 suicides per 100,000 children ages 5-12 during those 17 years. Compare that to 7.04 suicides per 100,000 people ages 13-18, or 17.39 per 100,000 for ages 18 to 65.

Child suicide rates rise with age. But, yes, the CDC has recorded suicides of 5-, 6- and 7-year-olds. From 1999 to 2015 (the most recent year for data), those numbers were two, four and eight, respectively.

Why does it happen?

Suicides for elementary school-age children have been little examined, but a study published last year in the journal Pediatrics saw some differences in factors from suicides in older children.

That study examined suicides in 17 states from 2003 to 2012, and broke down the factors among ages 5-11 and 12-14.

Relationship problems – such as arguments or other issues with friends and relatives – were the most common factor for both groups. Given their ages, the problems, naturally, were more likely to involve boyfriend/girlfriend issues in the older group.

Documented mental health problems were equally prevalent in both groups (about 33%). But differences in the types of mental issues were intriguing.

Attention-deficit disorder was more common in the 5-11 group, whereas the 12-14 set was more likely to have had been diagnosed with depression, lead study author Arielle Sheftall said.

That might mean the younger kids are more susceptible to responding impulsively to problems, said Sheftall, a research scientist at the Center for Suicide Prevention and Research at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

“I think having (the) information that we are seeing ADD/ADHD in kids (5-11) dying by suicide may help us to intervene differently in that age group,” Sheftall said.

Most are boys

By far, most children under 13 who kill themselves are boys: 76% of those who died in 1999-2015 were male.

GET HELP

That dovetails with research showing most of those taking their own lives across all ages are male. That same research, however, shows females attempt suicide more frequently.

But Sheftall said it’s not yet clear how many boys and girls ages 5-12 attempt suicide.

Separate research presented in May showed the number of children ages 5-17 who were hospitalized for suicidal thoughts or actions in the US doubled over nearly a decade.

A growing racial divide?

Sheftall’s team found something else: 36.8% of the 5-11 set who died by suicide were black – nearly double the rate reported in the same demographic group between 1993 and 2002.

The researchers were keen to see whether there were differences in precipitating circumstances among races, citing previous research showing that “black youth may experience disproportionate exposure to violence or traumatic stressors,” and are “less likely to receive services for depression, suicidal ideation and other mental health problems.”

But “when potential racial disparities in precipitating circumstances … were examined in the current study, few differences were found,” the authors wrote.

Experts: More research is needed

Sheftall said more research is needed, both to understand the increase in suicide rate in black children, and to determine whether and how suicide prevention efforts should be tailored to preteens.

Pre-13 suicides have been understudied, Sheftall said, largely because it’s hard to imagine children this young want to kill themselves.

“That’s why we’re making an effort to say, ‘Yes, this is occurring. Now, what can we do to help?’ “