Story highlights

Hail might become less frequent, but it will be more damaging, a new study suggests

The greatest impact will be to current hail-prone areas

Climate change is likely to reduce the number of hailstorms across North America in the coming years, a new study says, but don’t get rid of your insurance policy quite yet. You will probably still need a new roof due to hail damage, as the research suggests the storms that do come will be more damaging.

According to the study, published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change, human-induced climate change is likely to decrease the number of hailstorms while increasing the size of hail in the storms that do form.

“As the planet warms, we are finding that we’re having fewer rainfall events, but when it does rain, it tends to be heavier. And that seems to be what – at least what our work is suggesting – it could be what’s happening with the hail as well,” said Julian Brimelow, a researcher with Environment and Climate Change Canada, a government department, and a co-author of the study.

The team used computer modeling simulations of hail growth to discover how hailstone growth will change. It ran models for the years 1971-2000 and 2041-2070 and then compared the data.

This is not a calculation you could do on the back of an envelope, Brimelow said. It took about six months to run the calculations for a 50-kilometer resolution model that includes most of North America, run for four time periods a day for the 30-year intervals, past and future.

“At the end of the day, we generated about a billion profiles,” he said.

Though the researchers weren’t surprised there would be less hail in the future, they were surprised it would be more damaging, he said.

Hail on the Plains

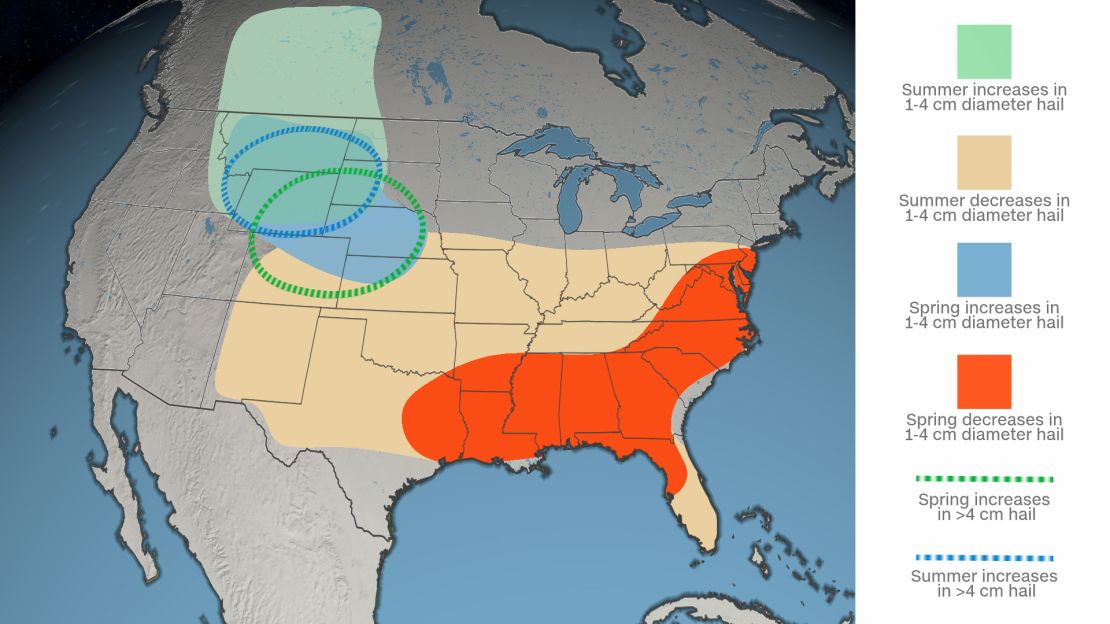

According to the study, “Drier and cooler regions are predicted to experience the largest increase in hail threat,” such as the Northern Plains, whereas warm and moist areas like the Southeast are likely to see a decreased threat.

The greatest impact was found to be areas already hail-prone, like the High Plains, increasing both hail frequency and size over spring and summer.

By comparison, “the number of severe hail days in spring is expected to decline markedly over the far southern and southeastern portions of the US; the signal is strongest near the Gulf of Mexico coast and over the Florida panhandle, extending northwards to the Appalachians.”

Billion-dollar disasters

In the past several years, billion-dollar hail events have been on the rise. There have been at least three billion-dollar hailstorms in the last two years, including one in just the past few months.

On May 8, one hailstorm in Denver during rush hour caused an estimated $1.4 billion in damage, mostly to vehicles stuck in traffic.

One could therefore expect that the amount of property damage will increase along with hail disasters.

But this all depends on where the hail falls, said Julie Rochman, president and chief executive officer of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety. A hailstorm in an empty field won’t cost anyone anything, but one in a city definitely will.

The institute is also doing its own hail research focused on what causes different types and sizes of hail, as well as hailstone softness and materials that can better withstand hail damage.

The new study will help add to the understanding of the types of environments that create different “flavors” of hailstorms, Rochman said.

Making progress in hail research

“It’s an exciting time for hail research,” Rochman said. “A lot of bright minds are looking into how hail will change in the future.”

The institute’s meteorologists were enthused by the new study, she said. It is consistent with some results and some data sets that the institute has published. And in the world of climate change, she said, hail hasn’t gotten a lot of attention.

Brimelow agrees that “virtually nothing” has been done in this space.

More research is being done in Europe, where hail impacts more people due to greater population density. In North America, hail research has mostly given way to the study of tornadoes since the 1980s.

Brimelow says the researchers will be happy to share their code with anyone who wants to run it for other parts of the world.

“We are just hoping this study spurs some interest,” he said.