Editor’s Note: Kenneth O’Halloran is the winner of the Open Competition category of the Syngenta Photography Award 2017. A selection of these works will be on display at the Syngenta Photography Award exhibition “Grow Conserve” at Somerset House in London until March 28.

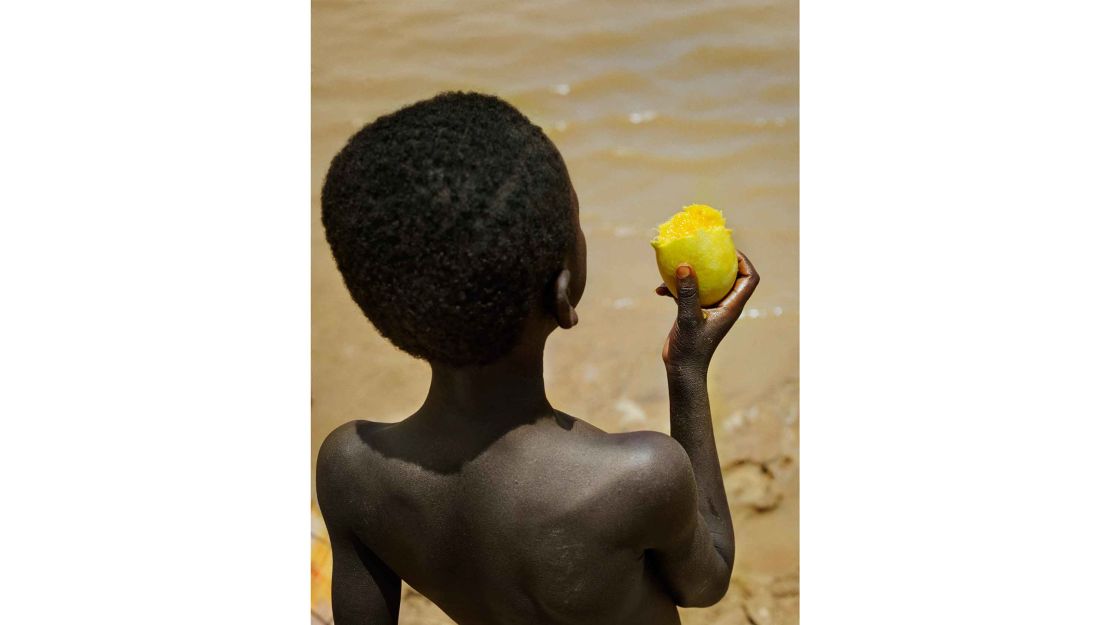

In the arid farmlands of Burkina Faso, a young boy takes a bite from a ripe, bright yellow mango, as he looks out over the muddy waters of Lake Bam and the local cattle who come here to drink.

Whether for fish or crops, his community of subsistence farmers relies on nature’s resources for their survival.

But not nearly enough rain has hit the cracked soil in recent years, and the lake is shrinking.

In an attempt to capture the struggles and beauty of life in smallholder farming communities like this, photographer Kenneth O’Halloran visited farmlands in Malawi, Kenya, Zambia, Burkina Faso and Togo, over the last couple of years.

His images depict the daily life of some of the world’s most vulnerable people.

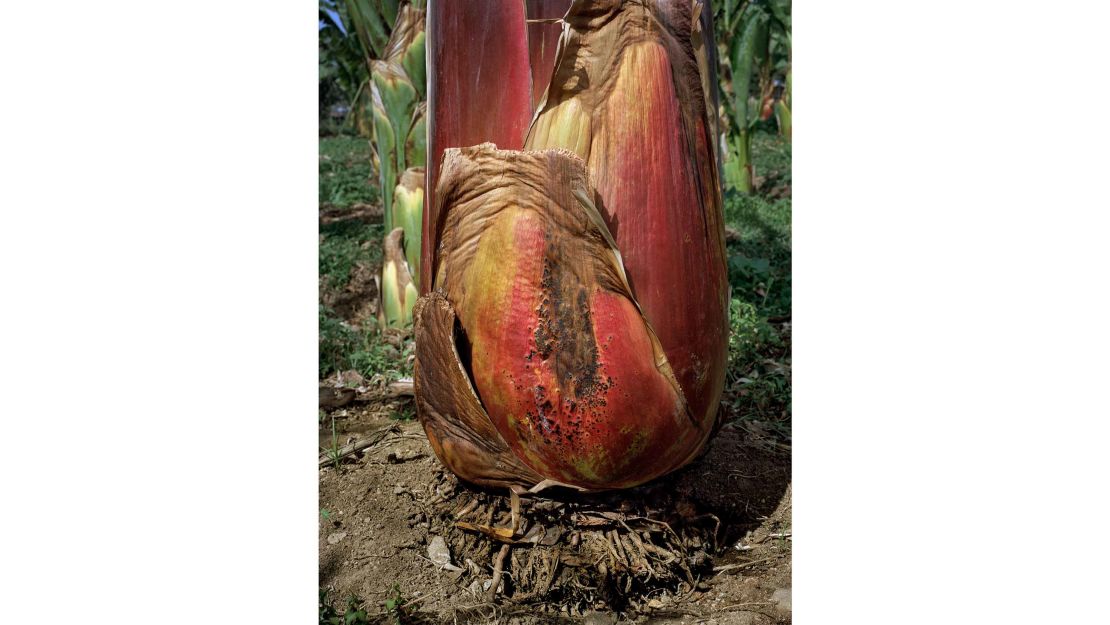

Agriculture in the belt of countries below the Sahara desert is particularly vulnerable to climate change, with some projections saying that the production of cereal crops in the region could fall by up to 30 per cent in the coming decade, according to Self Help Africa, a non-profit organization who operate in the area and supported the photographer’s work.

Shorter growing seasons, a decrease in rainfall, and yet occasional destructive flooding all contribute to the vulnerability of the people in the region, who depend on their crops for their survival.

Without water, nothing grows, but too much, from heavy rain and flash floods, can create problems too.

At a stop in a village in the Centre-Est region of Burkina Faso, O’Halloran met a young man digging for groundwater with a shovel.

His community hopes the well will help boost their crop yield, in an attempt to adapt to a changing climate which has brought on hotter summers and poor harvests.

The images show how climate change directly affects poor, rural communities, the photographer Kenneth O’Halloran told CNN.

“They have been forced to accept that rain-fed agriculture will only provide them with a supply of food for part of the year,” he says.

In 2014 and 2015 upwards of two million people in Burkina Faso received food aid during the so-called hungry season – the months after the year’s store of grain has been used up and before the next harvest, according to O’Halloran.

“In the past they used to grow enough to carry them through eight or nine months, they told me. But no longer.”

O’Halloran’s photos “Rural Africa” are currently on display at the Syngenta Photography Award 2017 exhibition, “Grow-Conserve,” at Somerset House in London until March 28.

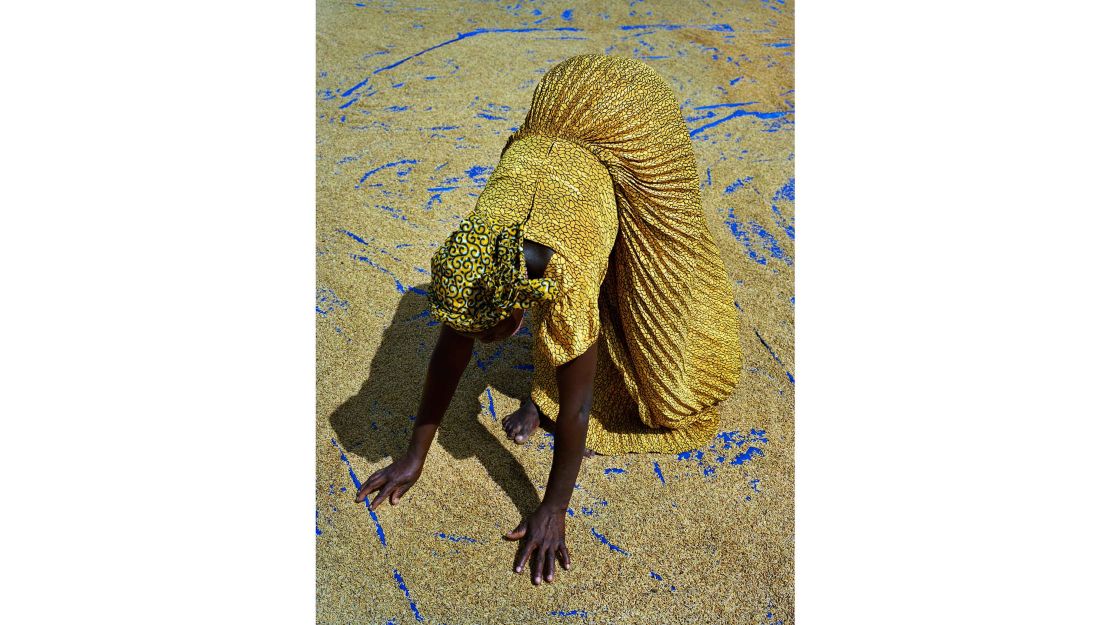

The image “Rice Farmer” (below) won the Open Category.

He was enthralled by the story of 38-year-old Sanwogou Lalle – a mother of five and rice farmer in Tonte Village, Togo – who lay out her grains to dry on a blue concrete surface in front of him.

“Sanwogou, who was just months away from giving birth to her fifth child when this picture was taken. She told me she was sending all of her children to school, and she had a dream that one day her son would become a doctor.”

More than half the farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are women, according to Self Help Africa, and in some areas women produce 70 per cent of the food grown on small farms.

Some 153 million people in sub-Saharan Africa – about 26 percent of people over 15 – suffered from severe food insecurity in 2014 and 2015, according to recent statistics from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

A distant memory for many of the world’s urbanites today, subsistence farming is still the main livelihood across sub-Saharan Africa, where 389 million people are estimated to live on less than $1.90 a day.

Around half the world’s extreme poor live in the region, according to the World Bank, who raised the threshold for extreme poverty from $1.25 to $1.90 in 2015.

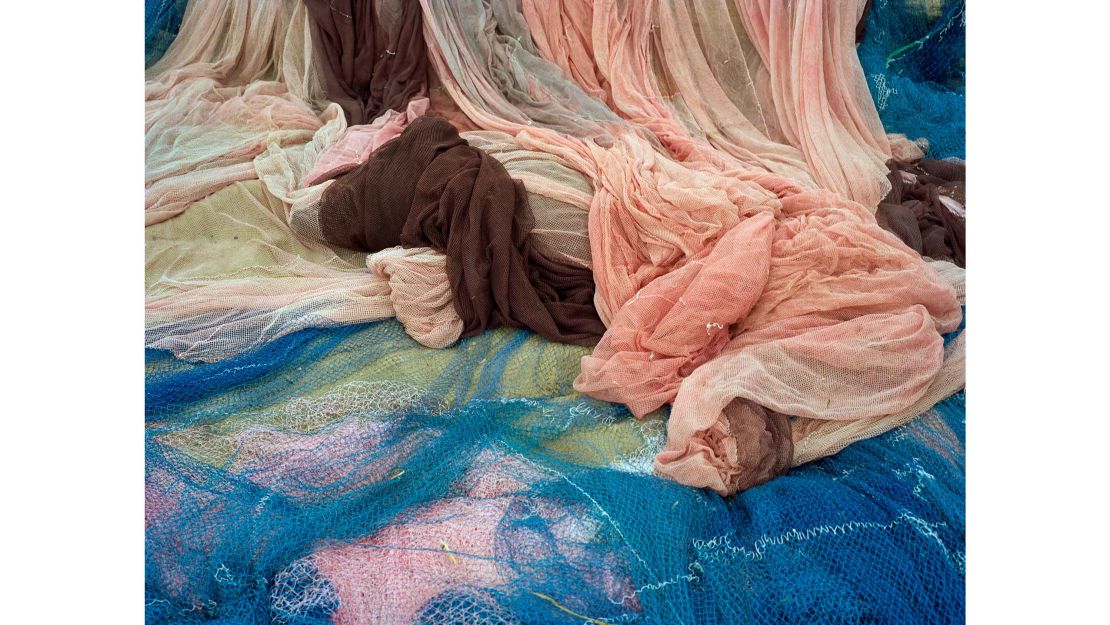

The challenges go beyond the confines of their farms. With many relying on local fish as well, threats of depleted fish stocks and lakes drying out leave them vulnerable too.

“The shrinking supply of fish from the lake has significant implications for food security in Malawi, where most of the population can rarely afford to buy meat, and rely on fish from the lake as a crucial source of protein, minerals and micronutrients,” says O’Halloran.

O’Halloran says the images send an important message of the reality of the people he encountered.

“They open a window into the real lives of real people, going about their daily jobs, working the land and the water, so that it will yield the food and the crops they need to sustain themselves.”

They illustrate the beauty and simplicity of rural Africa, where life is “timeless”.

“The way of life, particularly in rural communities, has changed little with the passage of generations. Because of this, many of the trappings of modern society – cars, roads, buildings, and housing – are entirely absent,” the photographer adds.

O’Halloran’s journey took him to some of the remotest corners of the continent. And he is likely to come back for more.

“Africa has always fascinated me. The early morning light, the colors, the landscapes and the people provide the photographer with an almost limitless array of options and possibilities.”

“I’ve traveled widely in Africa, and have developed a great love for the continent and its people.”