Story highlights

Rwandan bishops asked for forgiveness for sins of hatred and disagreement

A statement from Rwandan bishops was read in the country Sunday

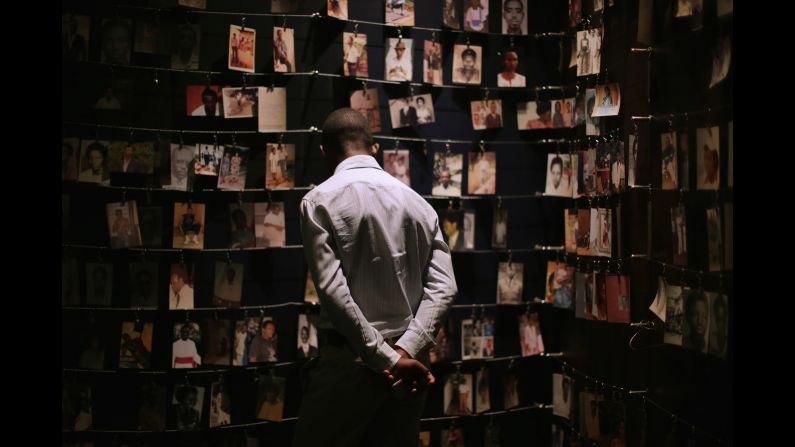

The Catholic Church in Rwanda has apologized for its members’ role in the genocide that saw hundreds of thousands of Rwandans killed in 1994.

Rwandan bishops asked for “forgiveness for sins of hatred and disagreement that happened in the country to the point of hating our own countrymen because of their origin,” in a statement read after mass in parishes across the country Sunday.

In 1994, Hutu extremists in Rwanda targeted minority ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus in a three-month killing spree that left an estimated 800,000 people dead.

Hutu attackers burned down churches with hundreds or thousands of Tutsis inside. The violence was triggered by the death of President Juvenal Habyarimana, an ethnic Hutu, in a plane crash April 6, 1994.

Although the church states it did not send anyone to participate in the killings, it acknowledges that its members were active, apologizing for “Christian leaders who caused divisions among people and planted seeds of hate.”

The church released its apology to coincide with the last day of the Jubilee Year of Mercy declared by Pope Francis.

Four Catholic priests were indicted by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda for their role in the genocide in 2001.

Among them was Rwandan Catholic Priest Athanse Seromba who was sentenced to 15 years in prison in 2006, increased to life imprisonment, for actively participating in the massacre of around 2,000 Tutsis who sought protection in his church.

The United Nations has criticized the Catholic Church in the past for its failure to apologize for its complicity in the killings.

Human rights groups have also joined in the criticism of the church and its role in the genocide.

Groups such as African Rights, who research the genocide, say there is “overwhelming evidence that church leaders maintained their silence in the face of genocide,” according to a 1998 report.

They argue that the small number of indictments do not accurately represent the church’s role in the genocide.

Some Rwandan commentators praised the apology as an important first step but said it didn’t go far enough.

“I think it’s a good start,” said Gatete Nyiringabo, who works with the Rwanda-based Institute of Policy Analysis and Research. “This shows the church is finally reforming.”

But Nyiringabo added: “It was a half apology,” noting the statement’s absence of any policy recommendations. “They didn’t indicate which bishops, and they didn’t speak of the Catholic Church as a whole,” he said.

While several priests have been tried in the UN tribunal and in local courts, Rwandan genocide scholar Tom Ndahiro said that others continue to operate without repercussions.

“There are many more [priests] who have not been held into account,” said Ndahiro.

“None of them have been held responsible by the Catholic Church itself and that is what is missing. You have civil courts that have tried them but the church has its laws and none of them has been held to account by the Catholic Church.”

“What they have done is a good step forward,” he said. “It’s significant only if it is followed by actions,” he added.