Story highlights

Yo-yo dieters are more likely to develop heart disease, new research claims

Weight cycling didn't increase the risk among overweight, obese women

Yo-yo dieting may increase the risk for coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death in post-menopausal women, according to a study presented to the American Heart Association on Tuesday.

Although previous research focused on the heart risks associated with obesity, study leader Dr. Somwail Rasla of Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island questioned whether women with normal weights could be putting their hearts in danger by on-and-off dieting.

There’s evidence that being overweight in midlife increases risk of dying from two types of heart disease, according to the heart association – coronary heart disease, in which blood vessels are blocked by fat and other material, or sudden cardiac death, where the heart’s electrical system suddenly stops working.

But it wasn’t clear whether losing or gaining weight in adulthood increased the risk of death from those diseases.

“We wanted to know if weight cycling is clinically significant,” Rasla said.

Does weight cycling effect our hearts?

To find the answer, researchers studied 153,063 post-menopausal women who self-reported their weights.

At the start of the study, women were asked to describe their weights as normal (with a body mass index less than 25), overweight (a BMI of 25 to 29.9) or obese (a BMI greater than 30). They also reported their adult weight histories, describing themselves as maintaining stable weight, steadily gaining weight, steadily losing weight or weight cycling (if they had lost and regained 10 pounds or more). Weight gained and lost during pregnancy didn’t count as weight cycling, Rasla said.

Researchers followed the outcome of their participants for more than 11 years, recording fatalities due to coronary heart disease and sudden cardiac death.

Over the course of the study, 2,526 coronary heart disease deaths and 83 sudden cardiac death deaths were recorded. Researchers categorized the deaths based on the women’s starting weights and their weight histories over time.

For overweight and obese women, weight cycling was not associated with the risk of heart disease-related deaths.

But the most surprising findings came from the group of normal-weight women who confessed to weight cycling. They were 3? times more likely to have sudden cardiac death than women with stable weights. Additionally, yo-yo dieting in normal-weight women was associated with a 66% increased risk of coronary heart disease deaths, according to the research.

“Normal-weight women who said ‘yes’ to weight cycling when they were younger had an increased risk of sudden cardiac death and increased risk of coronary heart disease, which can lead to heart attacks and other serious issues,” Rasla said.

The frequency of weight cycling – how often the women had lost and regained 10 pounds or more – was also a risk factor. “The more cycling, the more hazardous (to their hearts),” Rasla explained.

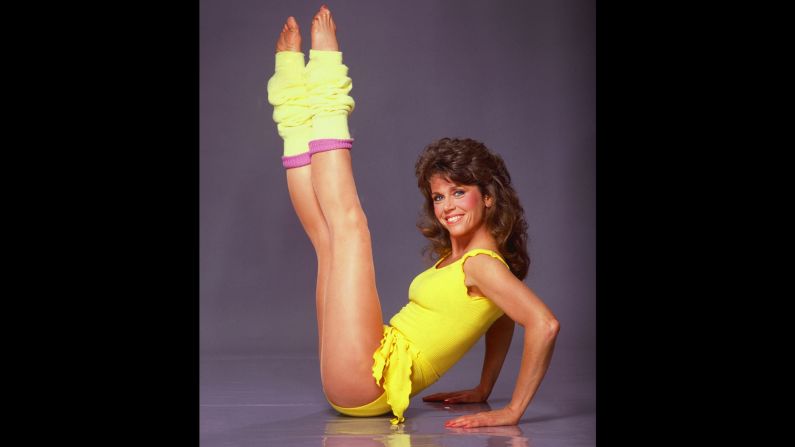

The dangers of yo-yo dieting

Women are more likely to change their weight frequently: According to Rasla, 20% to 55% of the female population of the United States has admitted to weight cycling, while only 10% to 20% of men have. Though it’s a common issue, the clinical significance of weight cycling isn’t always agreed on.

“Some studies say weight cycling has no effects on health,” Rasla said. Others claim that it can cause cancer, diabetes and other illnesses.

According to Rasla, one reason weight cycling may be harmful is “overshoot theory”: When someone changes weight frequently, he explained, gaining weight increases health risk by raising blood pressure, cholesterol and body fat. When she loses the weight, these levels drop, but not all the way to her healthy baseline, because her “normal” state was overshot by the weight gain. If these cycles keep repeating, the woman’s health will decline, even if she appears “normal.”

“The appearance of health can be deceptive,” said Dr. Michael Miller, a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine who was not involved in the new research. “You can look and appear healthy, but you don’t know what your risk factors are.”

As a cardiologist, Miller often encounters the effects of weight cycling in his patients, particularly middle-age women. “Yo-yo dieting can result in fluid shifts and electrolyte changes, such as potassium, that can cause deadly heart arrhythmias in susceptible middle-aged women,” he said.

Men are also negatively affected by weight cycling, but Miller sees the condition “more in women than men.”

“Popular diets want you to lose weight quickly, often by reducing your caloric intake by 500 to 1,000 calories a day,” he said. When this happens, the dieter’s levels of electrolytes, calcium and magnesium are depleted, which can be very hazardous to the body. “You should never lose weight in a drastic fashion,” he said.

“Under normal conditions, we shouldn’t be putting on or losing weight,” Miller continued.

“If someone is a normal weight, keep it stable,” Rasla agreed.

If a patient wants to lose some weight, Miller warns not to lose more than a pound a week. Instead of restricting food, he suggests eating a healthy diet and increasing energy output, or physical exercise, by about 300 calories a day.

Dr. Naveed Sattar, a professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow who wasn’t involved in the study, emphasizes that weight loss is still a healthy choice for many people.

“This study does not change the fact that overall evidence shows the value of intentional weight loss where lifestyle changes lead to beneficial weight change,” Sattar said. “If we look beyond this study at the totality of evidence, it shows us that if women (or men) try to lose weight intentionally, then there is no evidence from trials that this does anything other than good, even if weight gain recurs.”

Outside factors?

Dr. Suzanne Steinbaum, director of Women’s Heart Health at Lenox Hill Hospital and a Heart Association spokeswoman, says the study “shows the real, true negative effects of what yo-yo dieting can do on our hearts, and this is very, very relevant and important for us to see and understand.” Steinbaum was not involved in the research.

However, she continued, “I don’t know how much emphasis we can put on this study, because it is an observational study” and is therefore not conclusive about the effects of yo-yo dieting.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

“In observational studies, there are always factors that can’t be adjusted for,” such as pre-existing unhealthy habits, Miller said. These outside factors may have triggered the women’s heart conditions, he explained.

“This study has limitations,” Sattar agreed. “Women of normal weight are less likely to be intentionally losing weight than overweight women, so this weight loss in normal weight women is much more likely to be unintentional and could be due to illnesses, and the study cannot rule that out. So, weight cycling in normal weight women may be disguising some underlying illness, and these same illnesses may also in turn increase heart disease risks.”

Rasla also noted that the data collected for the study were self-reported, and the participants could have given biased answers. For future studies, he hopes to see participants’ weights monitored for better precision.

Miller is hopeful about the study results and future research on yo-yo dieting’s effects on heart health. “I think it’s a great start,” he said.