Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writer.

Story highlights

Gene Seymour: We need to talk about things that make us uncomfortable in dialogue on race relations

Americans of all races and classes must acknowledge common cultural bonds, he says

Among the results of the recent deadly police shootings in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Charlotte, North Carolina, is the additional jolt of grim reality enhancing the rap artist T.I.’s video of his “War Zone,” which depicts scenes of excessive, at times deadly police force used against unarmed citizens and other incidents of harassment. The blunt, brutal twist is that racial roles are reversed to show the police as black and the victims as white.

It’s a provocative approach that has people talking. Which is good: We have a lot to talk about in this country when it comes to race. Maybe that’s why so many of us try to avoid what we continue to euphemize as “our ongoing national dialogue.” And when we can’t avoid it, we try to keep it contained within boundaries familiar and safe – in other words, terms we can live with, guaranteeing that what we believe – whether “we” are black or white – will always be validated.

Guess what? That gets us exactly nowhere.

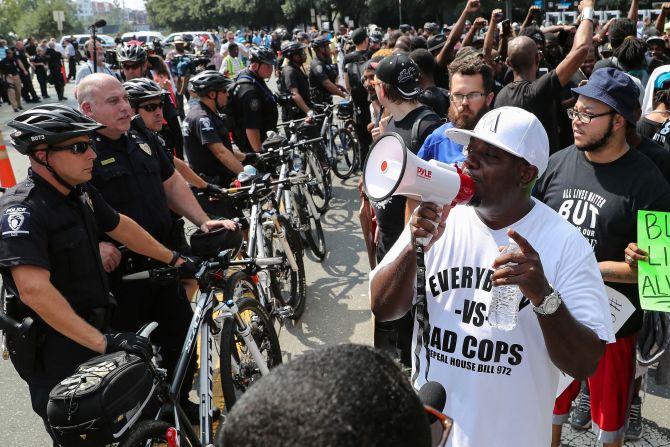

As long as this “dialogue” spins around in a cul-de-sac of accepted wisdom, recycled bromides and, worse, unyielding biases, the conversation, which everybody from the President on down insists is crucial to our survival as a democracy, will forever chase its own tail. The Black Lives Matter movement and what protesters believe to be a lack of legal and moral accountability in excessive police force against unarmed black citizens seem at this writing to have placed Americans of all ethnic, religious and racial persuasions in locked positions, where some refuse to look away and others can’t do anything but.

To break that cycle, we’re going to have to expand our capacity for reason and imagination. We need to stare at things that make us uncomfortable and take our time before dismissing them outright. If we’re still uncomfortable … well, then we’re going to have to talk it out. And keep talking, even though it likely won’t make us feel any better.

Which brings us back to T.I. The rapper recently appeared on Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show With Trevor Noah” to talk about his recent work. After a clip from “War Zone” was shown, Noah asked T.I. if this work aspired to increase the intensity of the dialogue on race:

T.I. Well, absolutely, I want them to take notice. … As disturbing as these images may be to watch on your television, just remember, these are fictional. … These things actually happened to people. These same events took the lives of fathers, sons, uncles, brothers, sisters. … These things actually happened to us. … So as disturbing as it is to watch it on your television, imagine how uncomfortable for us it is to live through these events … in reality.

Trevor Noah: This is always a tough question. … You get people who say, I hear you guys saying you want justice. I hear all hip-hop stars and fans saying this is not right. But then, in hip-hop, people are talking about guns … shooting. … People are saying things like, f*** the police. How is this helping the dialogue? As a hip-hop artist, how do you reply to that?

T.I.: Well, first of all, I think that people need to take into consideration that hip-hop traditionally has always been a reflection of the environment the artist had to endure before he made it to where he was. So if you want to change the content of the music, change the environment of the artist and he won’t have such negative things to say.

Protests over Charlotte police shooting

There’s a lot to unpack from this exchange, and maybe the best way to do so is to present one’s own response in four parts, point by point:

1. If, as Noah says, there are those who accuse hip-hop artists and fans of employing a double standard when it comes to violence against black Americans, then it sounds to these ears as yet another cop-out, an excuse to avoid confronting the repercussions of the often shocking images we’ve all seen in the last couple years of unarmed African-American men and boys being shot by police. Hypocrisy has its own way of chasing its own tail while presuming to track it down in others.

2. Then again, the kind of inquiry into root causes of violence – what T.I. labels “the environment” – has been noticeably AWOL in our public discourse since the 1980s as the center of American political discourse edged more to the right. At the same time the examination of economic and social factors behind street crime was considered by increasingly influential conservative politicians and pundits as tantamount to “making excuses” for or “coddling” criminals. The more recent police shootings have marked a shift in such emphasis. But even as that adjustment continues, there are now and will continue to be arguments over whose responsibility it will be to change that environment: the minorities who live in the community or the nation’s political and economic powers.

3. And to be clear: There are a lot of black people who didn’t grow up in “the environment” who are intimately, urgently engaged in Black Lives Matter and other movements protesting excessive force. Not all African-Americans began life as “children at risk,” and neither they nor, I suspect, many of the people who live in poor or working-class communities are exactly enthralled with the violence that has put minority neighborhoods in fear and peril.

4. I don’t think real change will start, however, until Americans of all classes and races begin to move beyond the binary classifications of “black” and “white” and begin acknowledging our common cultural bonds, the things that make us what the late African-American novelist and critic Albert Murray memorably labeled “Omni-Americans.” It’s label that rejects classifying whole parts of the American people in reductive, sociological boxes and begins sharing how what is classified as “black” and “white” in our culture often overlap – in our pop music, for instance, and also in our sense of a common national origin and destiny. Sorting all this out is complicated. But as our greatest thinkers and activists recognized from our nation’s inception, it’s also unavoidable if we want to move ahead.

As I said, we have a lot to talk about. Even more than all this. Give credit to Noah and T.I. for recognizing it.