Story highlights

New study offers hope for preventing breast cancer in high-risk women

Scientist used the drug denosumab in mouse experiments to halt breast cancer growth

Scientists might have just pinpointed a nonsurgical way for women at a high risk of breast cancer to minimize their chances of developing the devastating disease.

About 12% of all women across the United States will develop breast cancer in their lifetime, according to the National Cancer Institute. However, about 65% of women with a mutation in the breast cancer gene BRCA1 will develop breast cancer by age 70.

Women with the mutated gene have very few options to minimize that risk. Most, including actress Angelina Jolie, resort to a mastectomy as a preventive measure.

But a new study, published in the journal Nature Medicine on Monday, suggests that a drug already on the market to treat osteoporosis could be another option in the fight against breast cancer.

The research shows that the drug, denosumab, can stop certain breast tissue cells with the mutation from morphing into cancerous tumors, said Jane Visvader, a scientist at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Australia and a co-author of the study.

“If this is an effective prevention strategy, then our hope is that it will be possible to prevent or delay breast cancer in women with a BRCA1 mutation and possibly other women at high genetic risk,” she said. “It would be great if this strategy could ‘buy time’ for women considering having mastectomies.”

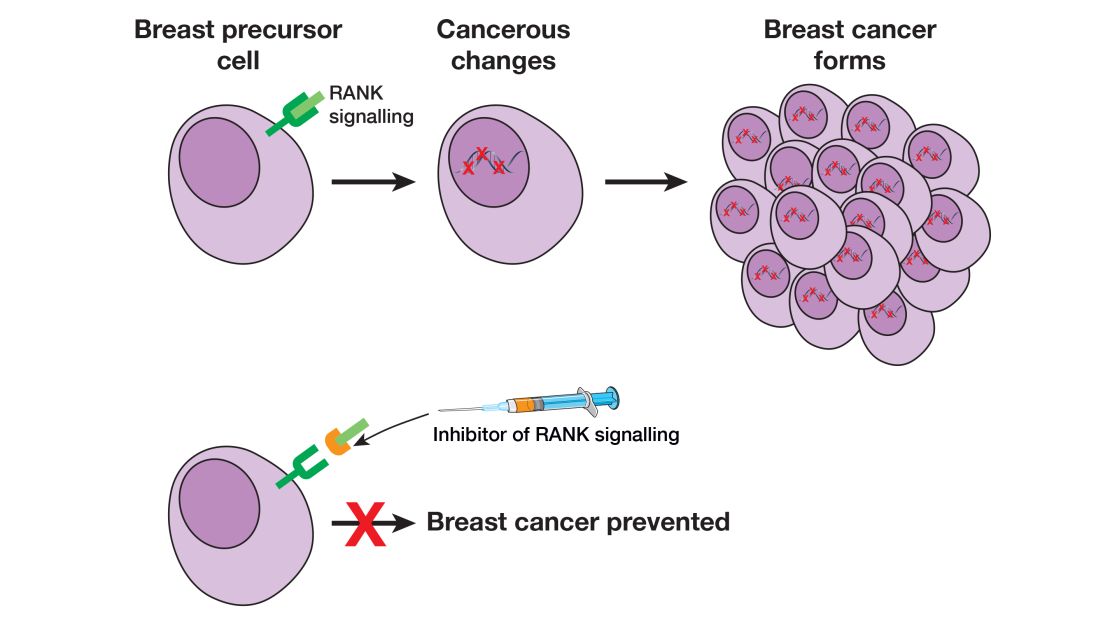

For the study, 33 samples of breast tissue with no BRCA1 mutations and 24 samples of breast tissue with the mutations were analyzed. The researchers noticed that a molecule called RANK was prevalent in a certain subset of cells in BRCA1 breast tissue. Those cells seemed to be the most likely to transform into cancer cells.

“We have now been able to pinpoint the precise culprit cells and were very excited to see that they express the RANK protein,” said Geoff Lindeman, a clinician-scientist at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and a co-author of the study. “Over the last few years, it has become increasingly clear from the work of several groups that RANK ligand, which switches on RANK, is an important regulator of cell growth in the breast.”

The researchers attempted to shut down RANK in those cells by injecting the tissue samples with a dose of denosumab, using the drug as an inhibitor. Denosumab is an approved drug known to target RANK ligand, and used to treat bone-related conditions, such as osteoporosis or bone loss in cancer patients.

The researchers then repeated this strategy using an inhibitor in mice experiments.

It turned out that the inhibitor was successful in delaying and preventing tumor growth in both the tissue samples and mice, compared with the samples and mice that didn’t receive the drug.

As part of a pilot study, Lindeman said, three women with a BRCA1 mutation were treated with denosumab, and the results “were promising.”

The researchers concluded that denosumab injections possibly could be used in women with a high risk of breast cancer as a preventive measure. They even called the study an important first step in achieving the “holy grail” of breast cancer prevention.

Of course, more tests and clinical trials are needed before denosumab can be considered for use as a breast cancer preventive drug.

Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center are planning to conduct a clinical trial. They hope to further examine the molecular changes that occur in breast tissue when a dose of denosumab is administered, said Dr. Francisco Esteva, professor at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, who was not involved in the most recent study.

Join the conversation

“The new study does not change any management or clinical use of any drugs at this point, but it provides data that can be tested in a clinical trial,” he said. “The data are compelling.”

Lindeman and Visvader said their research team is also hoping to contribute to a large international collaborative clinical trial, starting within the next two years.

“Of course, results from a large clinical study would take time: up to 10 years,” Lindeman said. “However, this does offer hope for the next generation of women.”