Story highlights

Scientists are working on a way to grow human organs inside animals through gene-editing technology

Ethical questions surround the idea, experts say

There’s a worldwide shortage of donor organs. Some people spend years on a transplant list, and others lose their lives while waiting.

But what if we could change that by growing organs?

It isn’t the premise of a science-fiction movie. Scientists believe they have the knowledge and technology to make this scenario a reality.

Researchers are in the very early stages of using adult stem cells to grow human organs. The twist: These human organs are being grown inside animals.

Every day, about 22 people in the United States die while waiting for organ transplants, according to federal statistics.

In an attempt to solve the global donor-organ shortage, researchers at the University of California, Davis have created embryos that have both human and pig cells.

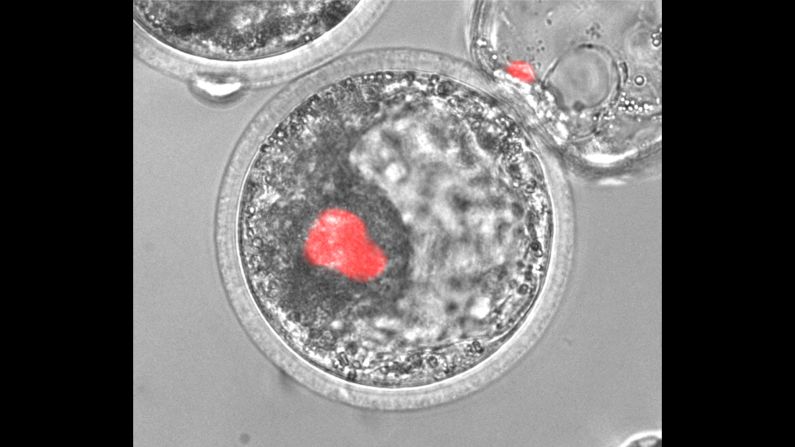

These cells are created by taking human stem cells from an adult’s skin or hair, using them in a pig embryoand injecting it into the uterus of a pig.

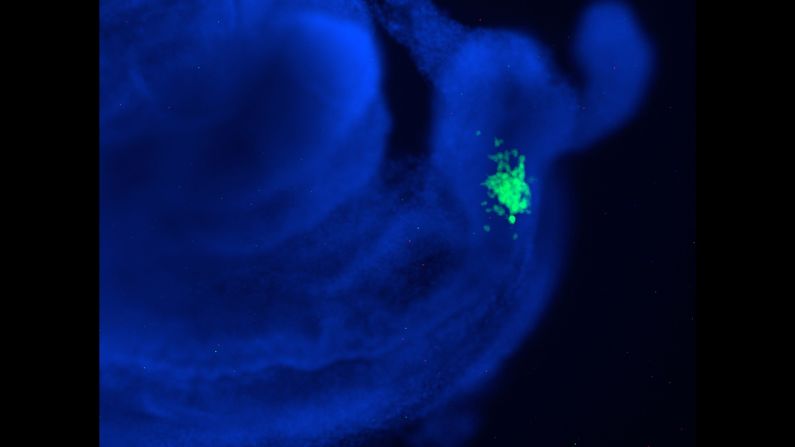

The embryo needs a few weeks to mature for scientists to determine whether the procedure worked, but after 28 days, the pigs’ pregnancies were terminated, and the cell remnants were analyzed.

Besides growing organs for transplant patients, this technology may help treat people with life-threatening diseases like diabetes, said scientist Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

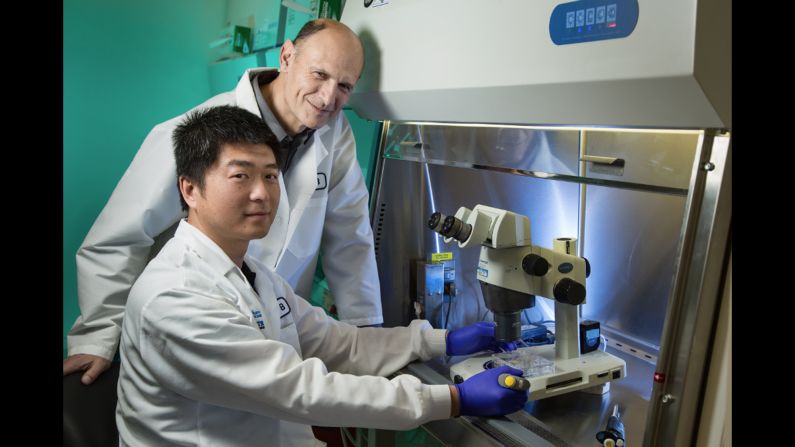

Belmonte is working with UC-Davis’ Pablo Ross on this research. Their work is being funded in part by the Defense Department and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

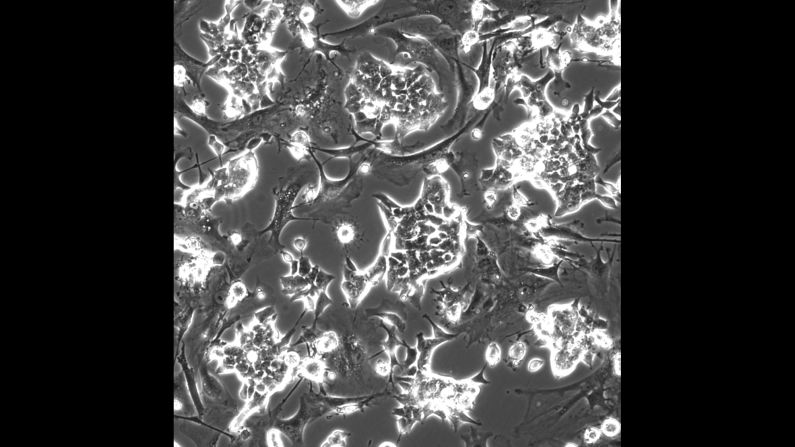

Getting to the point of creating human-animal hybrid organs is possible because of the combination of two breakthrough techniques in stem cell biology and gene-editing technology.

Scientists are able to knock out a section of an animal’s DNA, such as the pancreas, so a pig embryo won’t have the information it needs to make that particular organ.

Then, stem cells come into play. Once injected into the embryo, the adult stem cells will start working on creating a pancreas. Since embryos don’t have immune systems, they can’t reject the foreign cells.

The next step, which Belmonte said is still a dream, is that old, damaged or sick human organs could be easily replaced, possibly saving thousands of lives each year.

When man and beast unite

What makes stem cells so special is that they can form any type of tissue.

The stem cells are injected into an embryo at such an early stage, when the embryo is just a few cells in a Petri dish, that they can essentially develop into any part of of an animal’s body.

That possibility also makes the research controversial.

The mix of human and animal DNA in modern medicine is known as chimera. The name is inspired by a monstrous creature from Greek mythology that is depicted as part lion, part goat and part snake.

The U.S. National Institutes of Health announced in November that it would not support this human-animal research after reviewing a presentation from scientists working in the field.

The institutes’ main concern involves the concept of chimeras acquiring a cognitive state. Scientists are essentially asking themselves what happens if human stem cells somehow start to create a human brain inside an animal.

It’s a major bioethical question, according to Paul Root Wolpe, director of the Center of Ethics at Emory University.

“If you were creating a pig with a heart made from human cells, is that OK? I think it is. There’s nothing magical about the human cell,” Wolpe said.

But the landscape gets murkier if there’s a possibility of an animal experiencing human thoughts, Wolpe explained. Mental cognition is an intrinsically human experience.

“This is pretty crude procedure. We are throwing stem cells into embryonic cells and hoping that it works out. We have to be really careful about that,” he said.

Although the risk of an animal acquiring human consciousness is slim – their brains are smaller than and different from humans’ – anything is possible, Belmonte said.

“We need to consider all the possibilities. Where the cells go is a major question. They can go to the brain or anywhere,” he said.

But the National Institutes of Health’s funding ban has drawn criticism from scientists, including Daniel Garry, a cardiologist who leads a chimera project at the University of Minnesota, who said the agency’s stance is inhibiting medical progress and creating a stigma around the research.

‘Personalizing’ the future of medicine

Other than transforming to essentially anything, human stem cells are important in chimera research because they can limit the chance of a human-pig organ being rejected by a transplant patient’s body.

“With the compatibility of these cells, this will open the door for personalizing medicine,” Belmonte said.

So why grow organs inside a pig, anyway?

The creature’s organs are almost the same size as ours, said Walter Low, professor at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Neurosurgery.

“The animal is acting as a biological incubator,” Low said. “If the stem cells were taken from a patient with diabetes, those stem cells are identical to the patient’s own cells.”

Low has been using stem cells to treat neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, a condition that affects the central nervous system.

This idea of chimera organs isn’t a new concept, Low explained. In 2010, Japanese scientist Hiromitsu Nakauchi, who is now a stem cell biologist at Stanford University, was able to grow a rat pancreas inside a mouse. This was a huge breakthrough in chimera research because rats and mice are different species.

Join the conversation

If we can grow a rat organ in a mouse, why not a human organ inside a pig? Low asked.

However, we’re not very close to growing a human organ inside a pig just yet.

Belmonte and other scientists are pushing forward in their research. They want to create life-saving organs and potential treatments for debilitating diseases, but that dream isn’t possible without funding and support, Belmonte said.

“If this works, it may change the practice of medicine,” he said.