Story highlights

Almost 20,000 people died of hepatitis C in 2014, an all-time high, CDC says

Many at risk are baby boomers exposed before the nation's blood supply was screened

New cases of hepatitis C doubled as well, mostly among young, white drug users

Hepatitis C-related deaths reached an all-time high in 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced Wednesday, surpassing total combined deaths from 60 other infectious diseases including HIV, pneumococcal disease and tuberculosis. The increase occurred despite recent advances in medications that can cure most infections within three months.

“Not everyone is getting tested and diagnosed, people don’t get referred to care as fully as they should, and then they are not being placed on treatment,” said Dr. John Ward, director of CDC’s division of viral hepatitis.

At the same time, surveillance data analyzed by the CDC shows an alarming uptick in new cases of hepatitis C, mainly among those with a history of using injectable drugs. From 2010 to 2014, new cases of hepatitis C infection more than doubled. Because hepatitis C has few noticeable symptoms, said Ward, the 2,194 cases reported in 2014 are likely only the tip of the iceberg.

“Due to limited screening and underreporting, we estimate the number of new infections is closer to 30,000 per year,” Ward said. “So both deaths and new infections are on the rise.”

“These statistics represent the two battles that we are fighting. We must act now to diagnose and treat hidden infections before they become deadly, and to prevent new infections.”

Silent but deadly disease

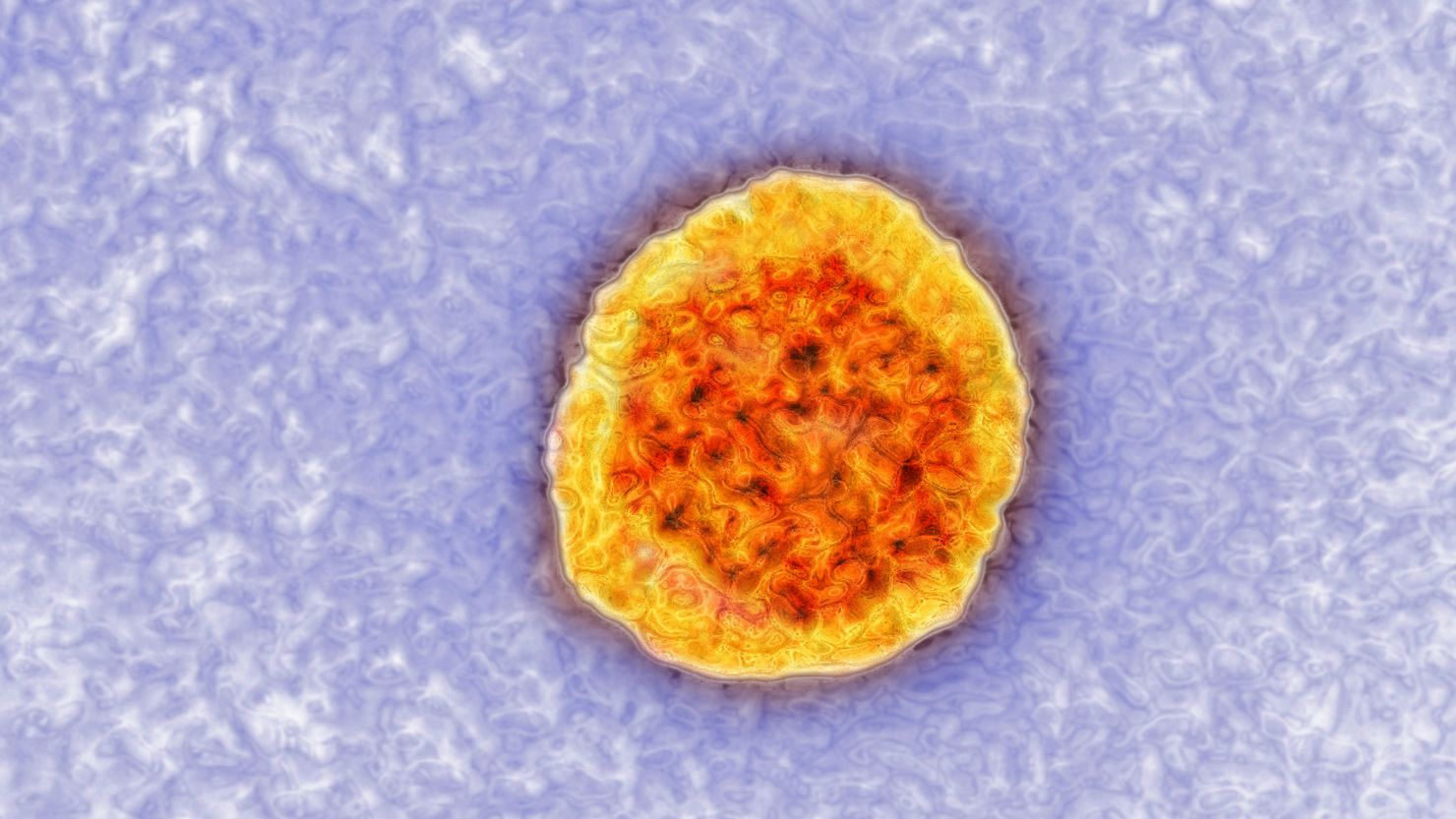

Hepatitis C is a viral disease that causes liver inflammation. Those with chronic or untreated infections can develop cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure. An estimated 3.5 million Americans live with chronic hepatitis C. The CDC estimates that half of those might not even know they are infected.

The greatest risk involves baby boomers – born between the years of 1945 and 1965 – who are most likely to have received a blood transfusion or organ transplant before 1992. That’s the year all donated blood and organs began to be screened for evidence of the virus.

“The average age of death is 59,” said Ward, “very much in the age group of baby boomers. But most people do not know they are infected, because people don’t really feel ill until the disease is very advanced.”

Data from death certificates shows a total of 19,659 deaths in 2014, up from 11,051 in 2003. Because death certificates often underreport hepatitis C, Ward said, that number could also be much higher.

“These deaths should not be going up, they should be going down,” Ward said. “We want every baby boomer to go to their doctor and get a one-time test. It’s a simple blood test, and can be done at any regular checkup or screening.”

If baby boomers follow this advice and get treatment if they test positive, Ward said, “more than 320,000 deaths can be averted over the next 15 years.”

Obstacles to treatment

Five years ago, treatment for hepatitis C involved weekly injections with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, a treatment associated with severe side effects that was only 50% effective. But drug manufacturers have flooded the market with new oral drugs, often prescribed in combination, that are between 80% and 95% effective.

The only drawback? The price: A three month supply of the drugs, which is the standard treatment course, can cost between $80,000 and $120,000. That led many insurance companies and state Medicaid programs to limit treatment to those with the most severe cases of liver disease.

“It’s the large number of people who need treatment that cause those sort of issues,” said Ward, adding that he sees some hopeful changes on the horizon.

“The cost of medication has declined. The most recent drug came out at half the price of the first released several years ago,” Ward added. “I believe the price of meds are heading in a very positive direction, so hopefully over time, that should result in the decline of these restrictions.”

Hepatitis C transmission

Today, most new hepatitis C infections come from sharing needles or other equipment used to inject illegal drugs. It’s much rarer to get a shot with infected blood on it, although that can occur in some developing countries where needles are reused due to poverty and a lack of medical supplies. A person might also get the virus from a tattoo or piercing if that equipment isn’t properly cleaned, but again, that is rare.

“The other transmission route we are worried about is mother to child transmission via birth,” said Ward. “We know that some of the younger illegal drugs users with new infections are women of childbearing age, and so we’re also trying to detect (it in) those infants and get them into treatment. That’s a work in progress.”

Join the conversation

Casual contact does not spread the virus, so you can’t get it from coughing, sharing food or utensils, or through hugging and kissing. Sexual transmission is possible, but the risk is very small unless you have many sexual partners.

If someone in your household does have the disease, precautions should be taken around any blood spills, such as nosebleeds. According to the CDC, the virus can survive at room temperature for up to three weeks, including in dried blood. Use gloves and clean up any blood with a dilution of one part bleach to 10 parts water.