Editor’s Note: Melissa K. Miller is an associate professor of political science at Bowling Green State University specializing in American politics. Sam Nelson is a senior lecturer at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and directs Cornell’s debate program. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors.

Story highlights

The first Nixon-Kennedy debate generated an enduring myth that style trumps substance

Melissa Miller, Sam Nelson: On-air faceoffs, especially during primary stage, are actually very informative

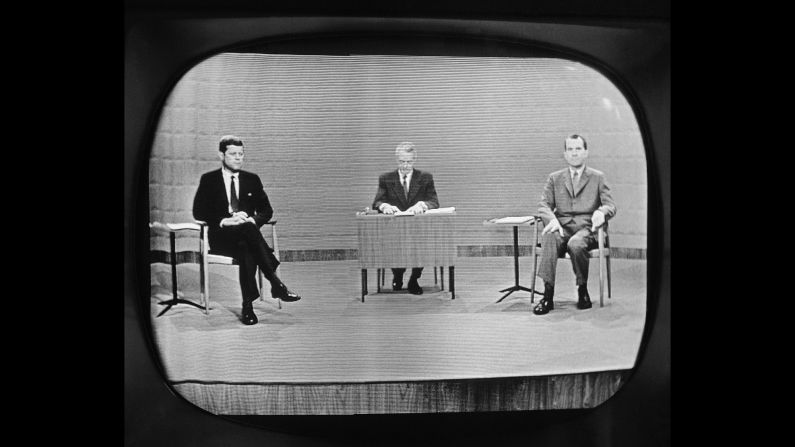

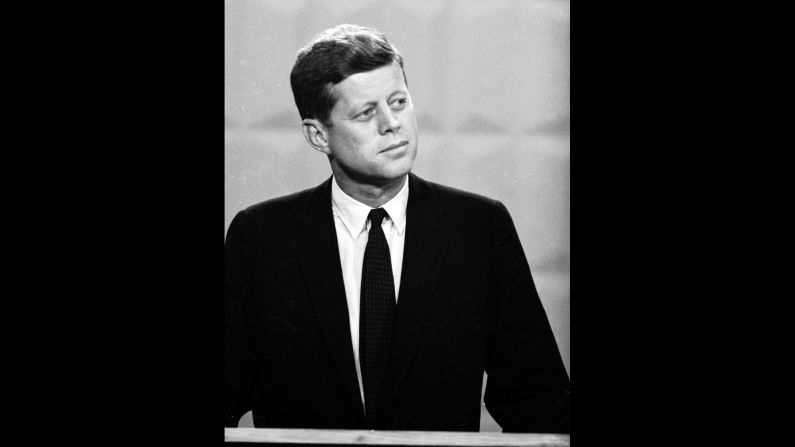

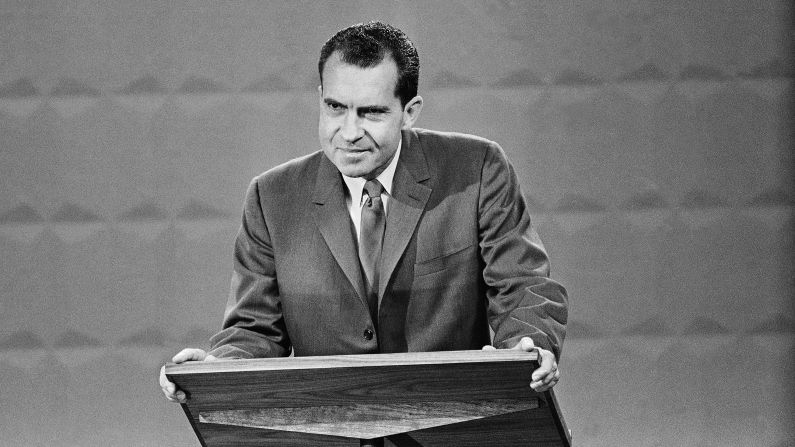

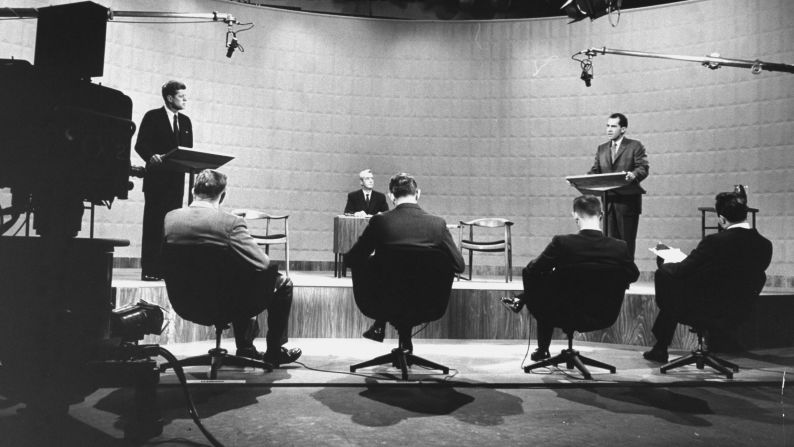

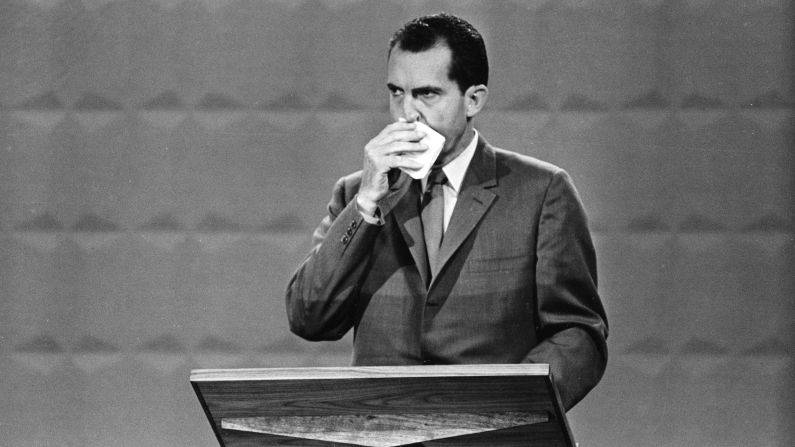

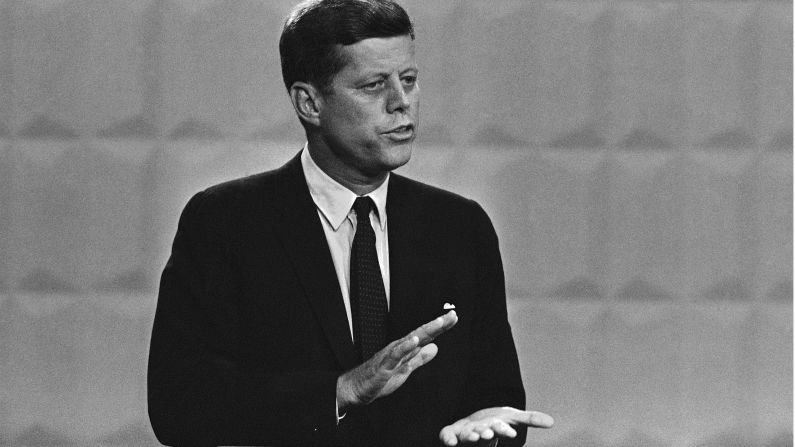

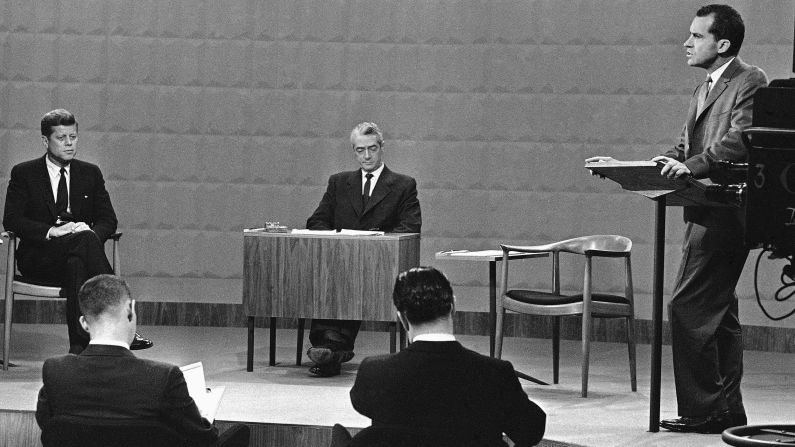

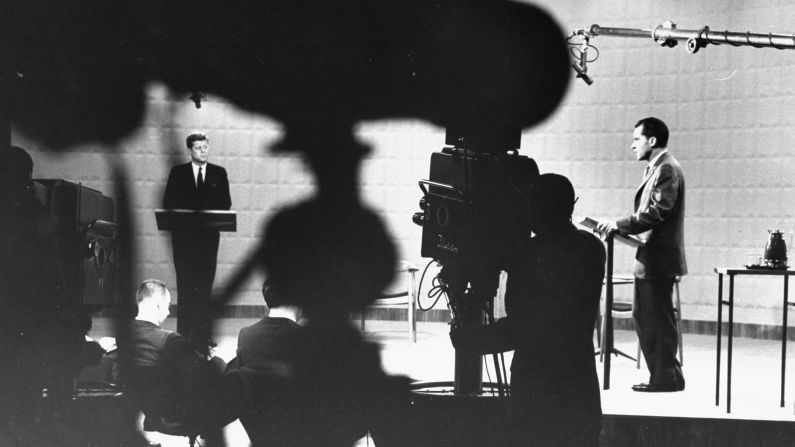

Ever since Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy entered CBS studios in Chicago on September 26, 1960, for the first televised presidential debate, these on-air face offs have generated complaint. Back then, Russell Baker, campaign correspondent for The New York Times, observed that Nixon and Kennedy seemed mostly concerned with “image projection,” while The Baltimore Sun wryly noted that “the ‘great debate’ wasn’t exactly great.”

Despite the criticism, the first Nixon-Kennedy debate generated historic viewership, with Arbitron estimating that two-thirds of U.S. households with televisions tuned in to watch.

That debate also generated an enduring myth that style trumped substance. The notion that Nixon won the debate among radio listeners while the more telegenic Kennedy won among TV viewers has been debunked by scholars, yet the view persists that televised presidential debates are mere vessels for candidates to project a presidential persona rather than a firm grasp of issues. Even today, critics continue to deride presidential debate as mere theatrical distraction, rather than a democracy-enhancing event.

We beg to differ.

Televised presidential debates deliver vital information, especially during the primary stage when voters must choose among candidates within a party, whose positions on important issues may seem to differ relatively little.

Subtle (and not so subtle) differences in issue positions are often revealed on the primary debate stage, as when Democrat Hillary Clinton challenged Bernie Sanders’ view that gun manufacturers and dealers should be shielded from liability lawsuits. On the GOP side, the debates have laid bare a fault line on immigration, pitting the more moderate positions of Jeb Bush and John Kasich against those of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz.

Debates make substantive differences plain. Let’s face it, most voters would be loath to sift through position papers posted by the nearly 20 candidates for president. Even political junkies would find such an exercise taxing. Debates provide a shortcut.

Unedited interaction

Moreover, most voters have scarce opportunity to see unmediated versions of the candidates unless they happen to live in Iowa or New Hampshire. The typical campaign event – not to mention 30-second campaign commercial – is highly produced and packaged. Debates actually allow voters to see the candidates interact with one another in a format unedited by high-priced consultants.

Televised debates also allow voters to see the candidates face tough questions in front of millions of viewers. How they comport themselves is one indication of their ability to handle pressure, an important presidential trait. Debates may not be a perfect barometer of a candidate’s ability to address a rapidly unfolding crisis, but what campaign event is?

Scholarly research on presidential debates provides additional reasons to celebrate the medium. Those who watch are more likely to become informed about the campaign and feel confident in their political knowledge. These effects are especially pronounced among those who are only marginally attentive to the campaign, as opposed to political junkies like us who parse every stump speech and sound bite. This effect has led some researchers to assert that debates are “an equalizer among the political information haves and have-nots.”

Do debates change voters’ minds?

Scholars have also studied whether presidential debates change candidate preferences among those who watch. Not surprisingly, virtually no effects on vote choice have been found when it comes to general election debates. Voters tune in predisposed toward the Democrat or Republican based on their own partisanship, and the debates are unlikely to cause dramatic shifts in allegiances.

Primary season debates are a different matter. Research suggests that voters tend to be uncertain about which candidate to back during the primary stage. This is especially true for marginally attentive voters for whom information gleaned from primary debates can significantly influence vote choice.

What about the charge that viewers only tune in hoping to see a candidate become unhinged or make an unrecoverable gaffe? What’s wrong with that? Put simply, the democracy-enhancing effects of debates accrue regardless of whether a viewer hopes to see Donald Trump or another candidate dress down a rival or make an embarrassing stumble.

Fighting for screen time

Criticism of debates has been especially loud in Republican circles this year. One reason is that individual GOP candidates have garnered precious little screen time in each so far. In October’s CNBC debate, for instance, the most screen time went to Carly Fiorina – a whopping 10 minutes and 32 seconds. As well, there has been a free-for-all nature on the Republican debate stage this season, with candidates bickering with moderators over time allotted to rivals and interrupting each other to be heard.

But these criticisms say more about the sheer number of candidates vying for the GOP nomination than the debate medium. With 10 candidates debating in prime time, not many minutes can be allotted to each. Candidates will naturally interrupt one another and call out moderators if they feel cheated on the time clock.

We have already seen the hosting networks, campaign operatives and party leaders tinker with the format and rules for the debates this primary season, and midcourse corrections are to be expected in a fluid campaign environment. Such adjustments are part of the broader evolution of presidential debates.

Presidential debates will continue to evolve in the United States. Over 60 million viewers watched Barack Obama and Mitt Romney debate on a single night in 2012. These are not the kind of numbers the Super Bowl pulls in (over 100 million), but they are impressive nonetheless.

Current high interest in presidential debates may not last across indefinite election cycles. Older voters are gradually being replaced by younger ones, who have adopted new ways of gathering political information.

We have come a long way since the grainy, black-and-white debate between Kennedy and Nixon in 1960. Today, in 2015, we could be in the Golden Age of televised presidential debates. Let’s enjoy it, appreciate it and celebrate it.