Editor’s note: This post was originally published in 2013.

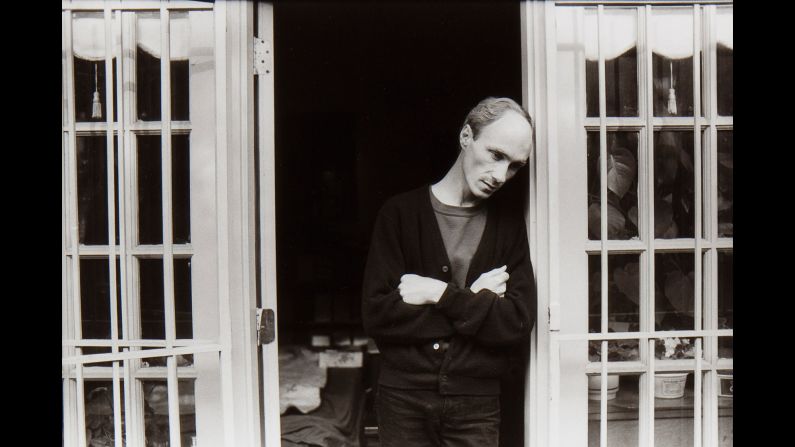

Before Billy Howard had finished the intro to his photo book of HIV/AIDS portraits, 15 of the people in the book had died.

He’d started the project in 1987 and wanted as many as possible of the people who had participated to get a copy of the book.

“It was a mad rush to the finish line,” Howard said. The publisher, Southern Methodist University Press, put this book ahead of all its other projects.

By the time it was printed in 1989, three more of Howard’s 80 or so subjects had passed away.

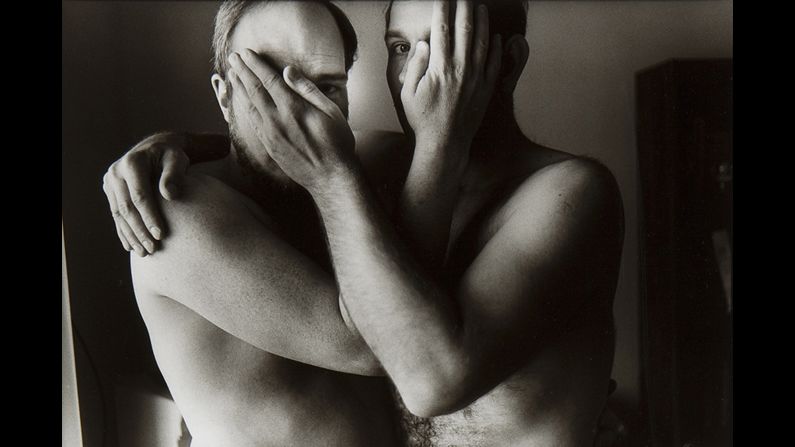

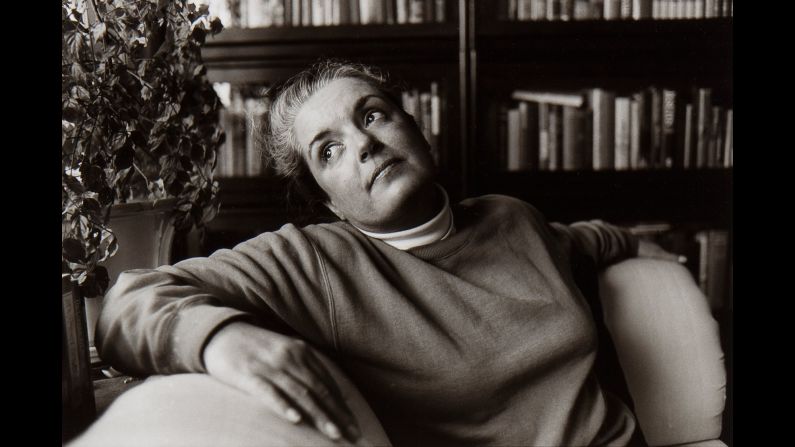

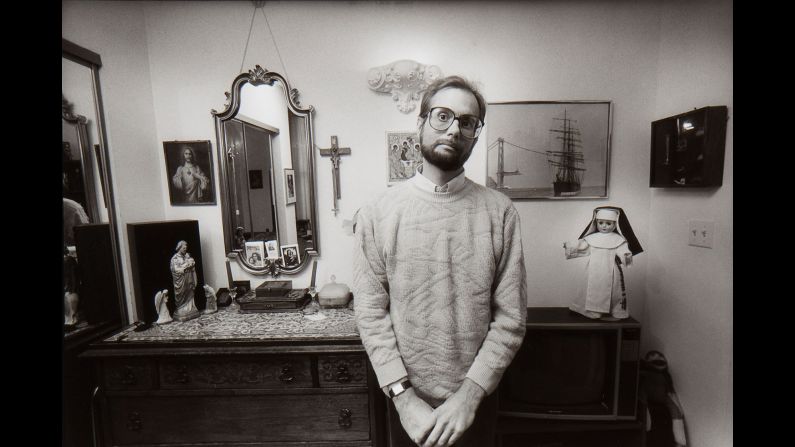

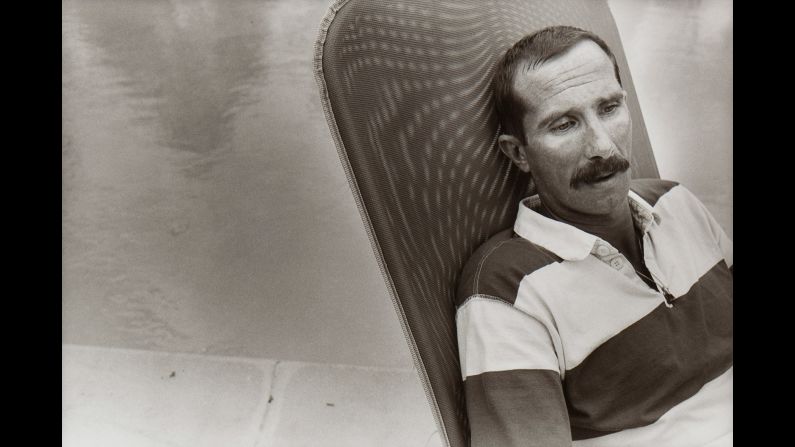

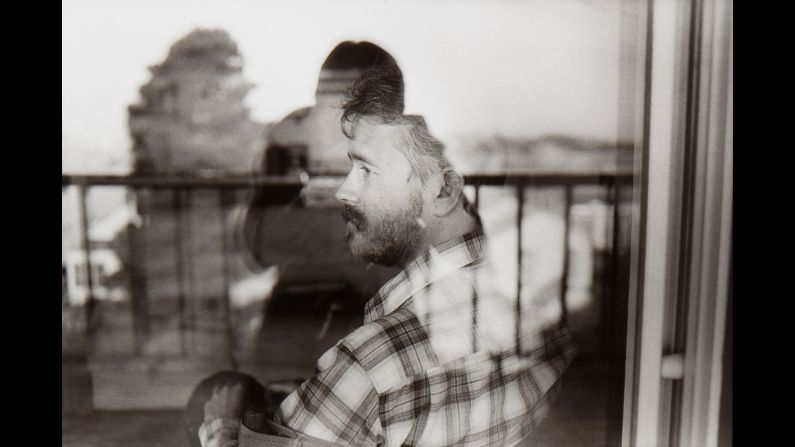

Howard spent a year and a half taking portraits of people with HIV/AIDS at their homes around the United States. He’d give them prints of their pictures and ask them to write about what it was like to live with the disease.

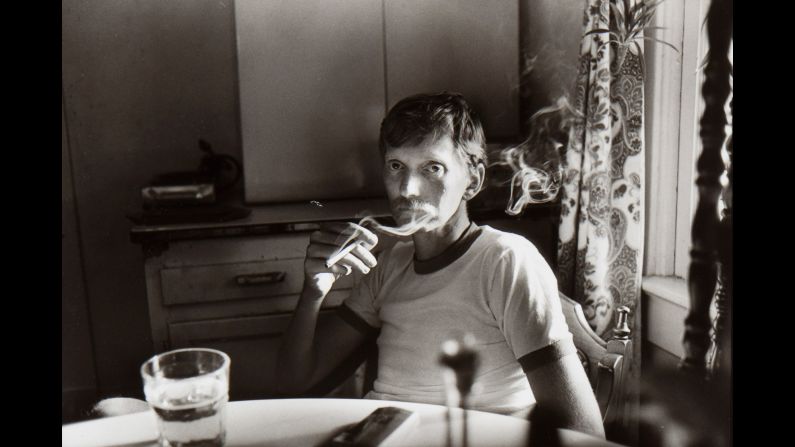

Twenty-five years ago, when Howard started this project, a person diagnosed with AIDS was expected to live less than 18 months.

“The shortest distance between life and death is… A.I.D.S.,” one man wrote on his print.

Some took months to get the print back to Howard. One man took a year. He told Howard it was because it felt as if he was writing his will. This inspired the project’s title, “Epitaphs for the Living.”

“The notes ran the whole gamut of human emotion,” Howard said. “I was surprised at how many upbeat ones there were.”

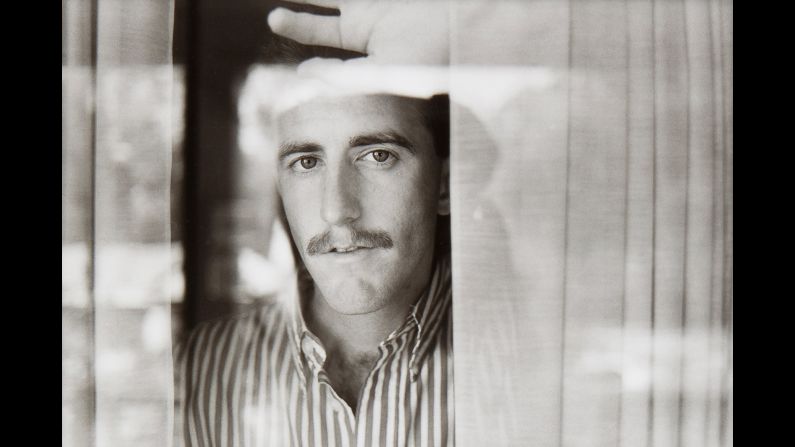

He’s drawn to people faced with challenges not of their own choosing. It brings out a grace that’s dormant in most of us, he said.

Howard said he’s never experienced this on another project, but every person he photographed turned immediately into an old friend.

“It’s because we get rid of all the bulls*** in our lives,” one man told him. “We either let you in completely or not at all.”

It was special to get so close so quickly, Howard said. But over and over, as soon as the connection was made, he’d lose the person. Some died before having a chance to write their notes on their portraits.

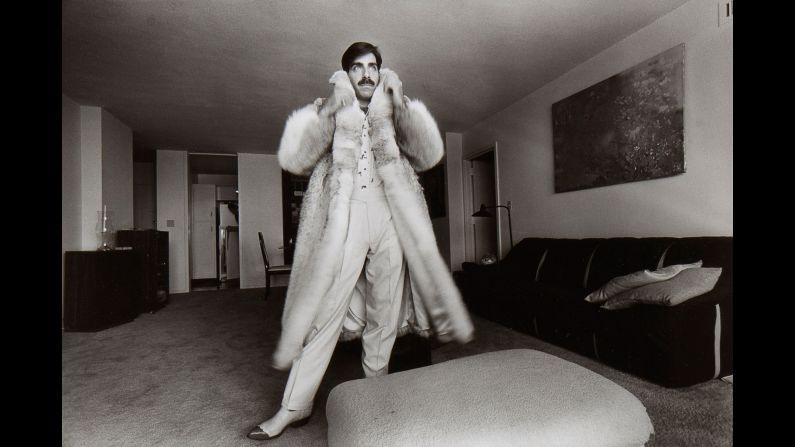

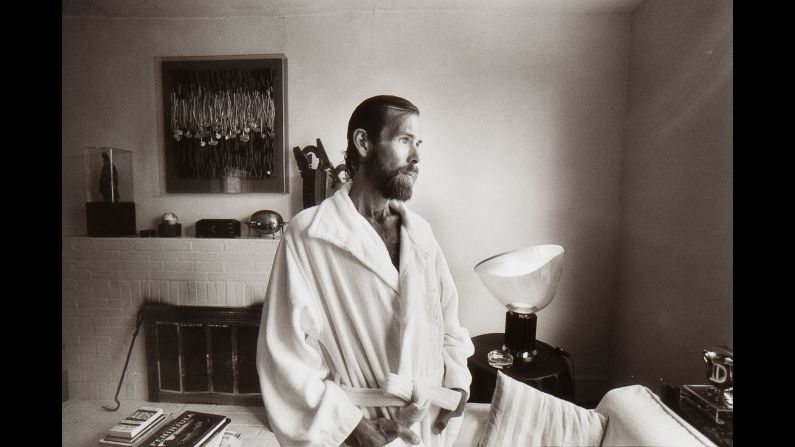

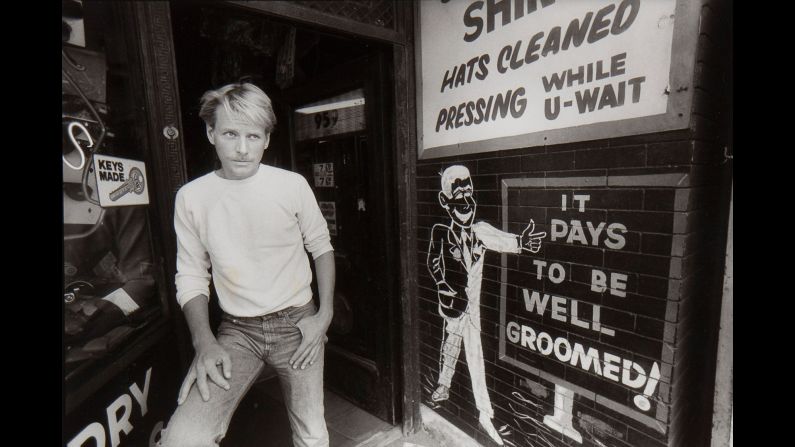

A positive HIV test result in the 1980s was not just a painful, ugly death sentence. It branded a person as one of society’s untouchables in the last years of their life. The first identified cases in 1981 were in gay men – a community already reviled by many people – who often contracted it through anal sex. Early media reports called it a gay disease, and some health care providers diagnosed people with Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, GRID for short. It appeared to be a plague on the male gay community and injection drug users, who would contract it through dirty needles.

People lost their jobs, they watched their close community plagued with AIDS dwindle, and some were ostracized by friends and family who couldn’t handle the stigma of the disease.

One subject, George R. Kish, had been diagnosed with GRID in 1982, when the disease had still not been identified. He had seen more than 60 friends die of AIDS by the time he participated in Howard’s project six years later.

“Thanks, dear Lord, for making my life with AIDS worth living!” he wrote. “But please, an end to this holocaust.”

Another man, John Mitchell Routh, wrote that he was tired of having no place to meet his family other than the parking lot at a Shoney’s.

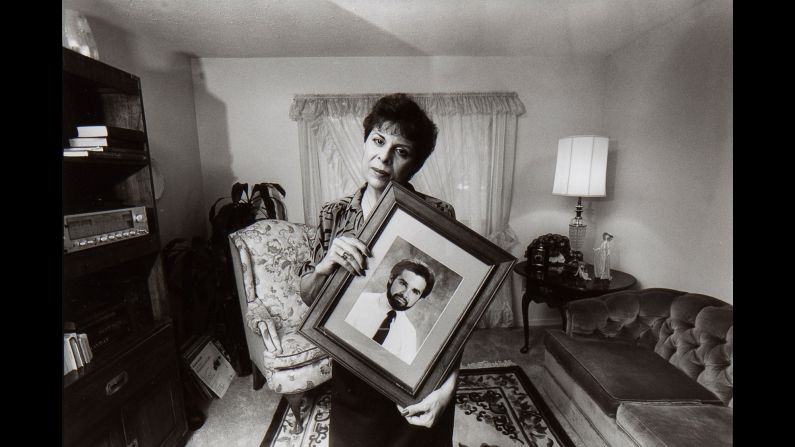

“You always wonder if you can make a difference with photography, and on the grand scale, I’m not sure,” Howard said. But he did transform the final days of his first subject.

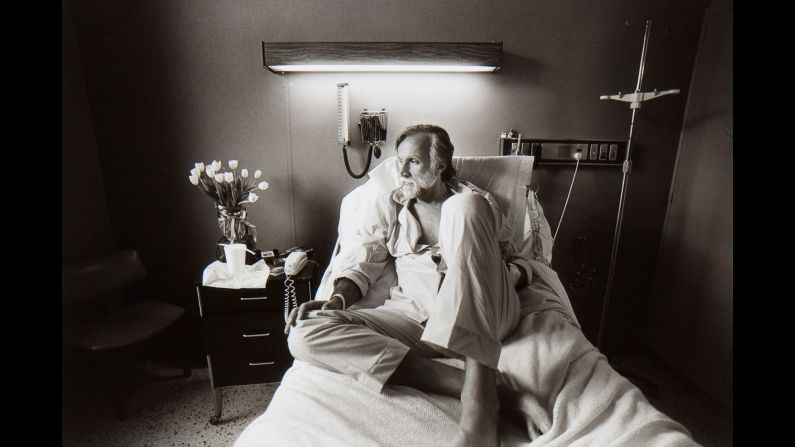

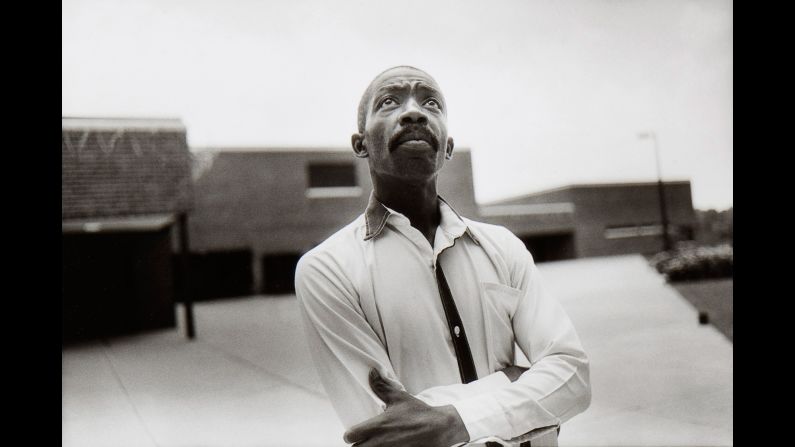

Howard met Ron while photographing him for a story on the HIV unit at Grady Hospital in Atlanta. Howard took Ron’s picture for Emory Magazine, then asked him what he thought about the idea of a portrait series of people with the disease and notes from them. Ron agreed to be the first subject, then found the next few at his support group. Howard would tell support groups around the U.S. about the project to find subjects but never asked anyone to participate.

Ron told Howard that he trusted him because the photographer shook his hand when no one else would touch him. At that time, police would wear gloves when around people with AIDS.

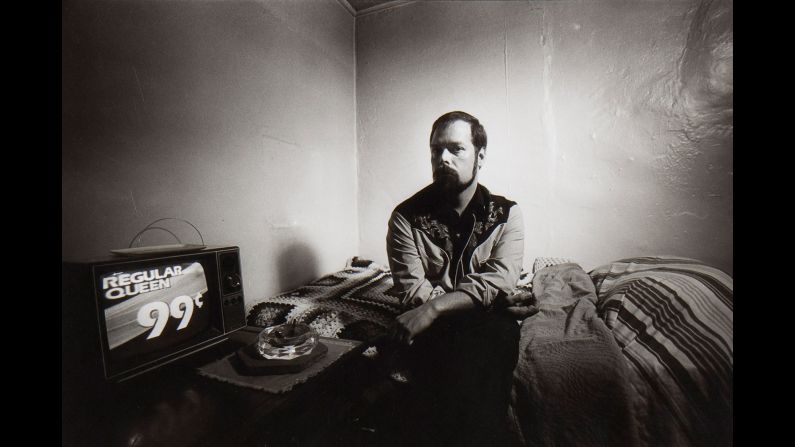

When Ron was diagnosed, he quit his job as a hospital administrator in Clayton County, Georgia, and moved into a rooming house. He was resigned to dying alone.

“I can talk openly about my illness now, but I still have fears,” he wrote on Howard’s photo of him. “I’m afraid I may die all alone. What’s more frightening is that no one will care.”

After Ron’s portrait he took for the series ran in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, friends in Clayton who hadn’t known that he was sick went to Atlanta and stayed with him until he died.

“It’s still an emotional experience,” Howard said, choking up as he told Ron’s story.

AIDS awareness and acceptance have taken huge strides since Howard worked on this project. Thanks to drug therapies and other medical advancements, people diagnosed with HIV now can have a near normal life expectancy. Recently, researchers announced a baby in Mississippi had been “functionally cured” of HIV, offering hope that the infection could be eradicated in infants globally.

Howard said he’s seen huge strides in the acceptance of people with the disease and the people with whom it was most associated, the gay community. He said he wishes that the change had happened faster, but he recognizes the transformation has been profound.

He credits it to the public learning more about people with the disease through media and personal stories.

“I wouldn’t do what I do if I didn’t think people would change,” he said.

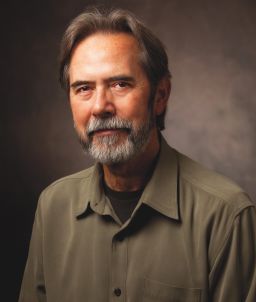

Billy Howard is a freelance photographer based in Atlanta. His book “Epitaphs of the Living” can be purchased on Amazon.com. You can also follow him on Twitter and Tumblr.