Story highlights

More than two dozen students have died because of hazing since 2008

CNN has learned that in five hazing-related deaths, institutions knew there was trouble before the incidents

Nolan Burch’s parents didn’t know what West Virginia University knew – that the fraternity their son was pledging had a history of bad behavior and was about to lose its charter.

Tucker Hipps’ parents didn’t know what Clemson University knew – that there were an unprecedented number of fraternity violations happening in the weeks their son pledged.

And Marquise Braham’s parents didn’t know what they say Penn State University allegedly knew – that there were concerns about their son’s well-being in the days leading up to his suicide.

All three sets of parents now believe they were kept in the dark by institutions they trusted to care for their sons.

The Burch, Hipps and Braham families share a common sadness – their sons are dead, lost to what they believe was hazing-related behavior. They’re three of the more than two dozen students who have died because of hazing at U.S. colleges and universities since 2008.

College Deaths

And, CNN has learned, through record requests and other sources, that in five hazing-related deaths in as many years, institutions knew there was trouble before the deadly incidents happened.

‘Occurrences of concern’

Nowhere on West Virginia University’s website did it say that Kappa Sigma fraternity had a history of, as the school now puts it, “occurrences of concern” – specifically referring to the fraternity “behaving inappropriately and hosting an unsanctioned event.” The fraternity was also warned about overcrowding in its off-campus residence.

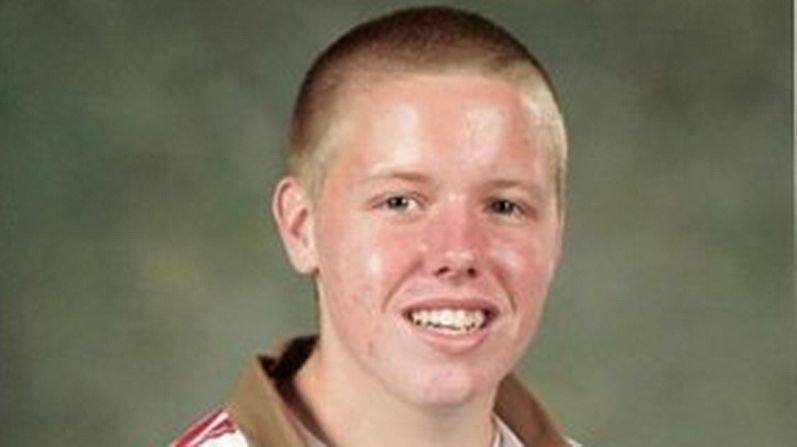

Burch, a WVU freshman, died following a fraternity hazing event in November 2014. His blood alcohol content was measured at 0.493, more than six times the legal limit to drive. His death led to the suspension of all Greek activities at WVU and criminal charges against two Kappa Sigma brothers.

Two days before the event, where police say Burch and others were blindfolded and forced to drink liquor, the national office of Kappa Sigma notified WVU that it was pulling the charter of the local fraternity chapter. According to a statement given to CNN, the national office directed the local chapter to stop holding functions. But that directive was ignored, according to the fraternity’s national office.

“They’d been in so much trouble they (the national office) put cameras in the fraternity house,” Burch’s mother, Kim Burch, told CNN. “The frat actually installed cameras.”

Kim and T.J. Burch say their 18-year-old son was not aware of the fraternity’s troubles when he decided to pledge. No one told him, and no one told his parents either.

“We had no idea, unfortunately, until Nolan passed, that there had been so many problems,” Kim Burch said. “It’s sad. It’s really sad. If we had known this was going on, we would have never let him join this fraternity.”

‘Unprecedented conduct issues’

That same semester, Tucker Hipps’ family had no idea that Clemson University was having a serious problem with fraternities. The university was considering a moratorium on all fraternity events, but decided just three days before Hipps died to hold off.

It would later come out that Sigma Phi Epsilon violated five rules while Hipps was pledging, including violations related to hazing, harm to person, alcohol and organizational conduct. The university did not answer when asked by CNN if officials were aware of those five SigEp violations prior to Hipps’ death.

Hipps, 19, died after he fell, jumped or was pushed off a bridge during a predawn run that was against the fraternity’s hazing policy. There’s an open criminal investigation and the family is suing the university and three fraternity members, who all have denied knowing how he died.

His parents say it was not for lack of trying that they did not know about the fraternity’s problems.

Hipps’ father, in particular, was opposed to his son joining a fraternity at Clemson.

“His dad was totally against it in the beginning,” his mother said earlier this year. Cindy Hipps said she’d done her due diligence, even attending a Greek orientation meeting, which she said put her mind at ease.

“After that class I felt better about it,” she said. “They said kids in frats have better time management skills, set study times, did it as a group activity. Those kids had higher grade point averages. All the things a mother wants to hear, I heard. I convinced his dad to let him do it. Never once did I ever feel like my child would be harmed in any way.”

When she checked out Clemson’s Greek life website, she saw only positive information, such as links to the average GPAs of each fraternity and sorority. There were two references to hazing policy, but nothing that explained which fraternities or sororities had been cited for violating those rules.

But at that time, Clemson officials were concerned about “unprecedented conduct issues over the course of first 3 weeks of school,” at several of the school’s fraternities, according to internal documents obtained by CNN.

After Hipps’ death, Clemson added a list of suspended fraternities to its website.

If Hipps’ already-apprehensive parents had known what was going on at Clemson, they say, they would have pulled their son out of Greek life immediately.

Dangers are not myths

West Virginia University, Clemson and Penn State are not the only universities that brag about philanthropy, brotherhood and connections for life on their Greek life websites. Most schools list only the positives.

Clemson’s says “Greek organizations do hold social events, but most of these do not include alcohol.”

Penn State’s goes as far as to say: “For many parents, the fraternity and sorority community reminds them of images of the movie Animal House. There are many myths about the fraternity and sorority community, but the reality is that men and women in fraternities and sororities are committed to their academics, volunteer their time in the community, develop and strengthen their leadership skills, and form a campus network with other fraternity and sorority members.”

That kind of language outrages Doug Fierberg, an attorney for the Braham family, who recently sued Penn State on the family’s behalf and who has handled dozens of university misconduct cases in his career.

“The dangers of fraternities are not myths. They are reality,” Fierberg said. “The failure by universities to tell the truth about the risks facing students in fraternities specifically related to hazing misuse and abuse of alcohol and other misconduct is the new battleground.”

“It needs to be changed nationally, because parents and students are entitled to timely and accurate information about the risks they face. And universities have no basis, morally or legally, to withhold that information from the university community,” he said.

Some universities don’t post a hazing policy on their Greek sites. For example, at West Virginia University, it’s posted separately on the campus police site. (West Virginia University told CNN it is considering a number of changes, including “better and more timely communication.”)

Others have listed it in online FAQs, several clicks away from the positives.

There are very few universities that list fraternity infractions on their websites, and even when they do, it’s often difficult to determine what the infractions really mean.

For example, after the 2008 alcohol poisoning death of Brett Griffin, 18, at the University of Delaware, Fierberg sued on behalf of the family and forced Delaware to change its Greek life site to list violations. But the list is vague, just listing things like “multiple violations” or “social policy violations” or “hazing/alcohol” without details of the incidents.

“You’re looking at best practices,” Fierberg said, referring to the University of Delaware site. “What’s ‘multiple violations’? Were people hurt? Was a student hospitalized? What does it take to get suspended?”

Northern Illinois University adopted a policy of putting sanctions on its website after the 2012 death of David Bogenberger, a 19-year-old pledge who was forced to drink alcohol and died. (Twenty-two brothers from the Phi Kappa Alpha fraternity were criminally charged and sentenced to two years of court supervision, plus community service.) Three months after his death, NIU made the change, but the list isn’t on the Greek life website – and it’s so hard to find, CNN had to ask the university to point out where it is. (It’s on a separate page, one for the Office of Community Standards & Student Conduct.)

The relationship between universities and fraternities can be confusing, since many of them reside off-campus and are chartered by national organizations. But Fierberg said universities violate their duties to students and parents when they create websites about Greek life and only include feel-good information, instead of an accurate and complete picture.

And national fraternities are no better.

The only major fraternity that lists its violations is Sigma Alpha Epsilon, according to Fierberg, and that’s because he sued SAE after the 2008 death of a fraternity pledge at California Polytechnic State University and forced it to list prior violations online.

Carson Starkey, 18, died of alcohol poisoning following an event where pledges were forced to drink alcohol, vomit, and drink some more. The SAE chapter at Cal Poly had a prior drug violation before the death, according to Cal Poly.

“(Universities) won’t give you the full information because it will confirm that what you believe is right,” Fierberg said. “Of course you have a zero tolerance policy. (Hazing is) illegal. … But why wouldn’t you tell parents it’s still going on?”

Fierberg said he suspects that the universities don’t even write their own language for these Greek life information sites, since many of them look the same. In fact, a Google search of “myth” and “Greek life” and “hazing” and “.edu” shows nearly identical definitions of hazing on the websites of dozens of schools.

Mental health emergencies

Marquise Braham jumped off the roof of a Marriott in Nassau County, New York, in March of 2014, the same year that Hipps and Burch died. A source close to the case says there was evidence of alcohol-fueled physical and sexual hazing prior to Braham’s suicide.

Fierberg is representing Braham’s family in its lawsuit against Penn State.

Fierberg claims the university was aware there were “serious concerns” about the “well-being and psychological health” of Braham, 18, in the days leading up to his suicide.

Phi Sigma Kappa told CNN it hasn’t seen the lawsuit and will not comment.

The police chief in Logan Township, Pennsylvania, where the satellite campus he attended is located, told local reporters that Braham had discussed hazing at his fraternity with an aunt and with several friends. The case is under investigation by the state attorney general, but no charges have been filed. The fraternity was suspended. Penn State said it couldn’t comment on Braham’s death, because of his family’s pending lawsuit, but admitted there are times when the university reaches out to parents to notify them of harmful situations.

“Emergency in this context includes mental health emergencies as well,” university spokeswoman Lisa Powers said in an email. “In general, and in accordance with privacy laws and practices, when we have a student emergency we balance the critical nature/seriousness of the situation with the student’s privacy rights as we make the decision to contact parents, or not.”

Many universities say they alert parents of health risks, such as when a student contracts a contagious disease, but there is no such pattern of reporting when it comes to other potential threats, like hazing.

In addition to Hipps and Burch, there is the 2010 death of Samuel Mason, 20, who was allegedly made to drink a bottle of liquor in an hour while pledging Tau Kappa Epsilon at Radford University in Virginia. Radford University says that chapter of TKE had been found in violation of university policy earlier that year for serving alcohol to minors at a fraternity social event. His family sued and settled with the national fraternity and several of the local chapter’s members.

And the death of Armando Villa, a 19-year-old at California State University-Northridge, pledging Pi Kappa Phi, who died during a hazing-related 18-mile August hike where, his family lawsuit alleges, he and other pledges weren’t given enough water. His fraternity had been cited for not completing required education programs and for holding unregistered events, and had just been reinstated after a suspension when the hike took place. A spokesman for the family says his mother, Betty Serrato, didn’t know about the suspension and says that if she had, she would have tried to talk her son out of pledging that fraternity.

Neither Radford or CSUN has sanctions posted on its website, although CSUN told CNN it is considering putting them online.

“It’s sad. It’s really sad,” Kim Burch said. “If we had known this was going on, we would have never let him join this fraternity. I never in my life thought I was sending a 17-year-old kid off to end up two months later gone. It’s repulsive. He would have been better off joining the Marines and going to war.”