Editor’s Note: Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff is the author of “The Making of Les Bleus: Sport in France, 1958-2010” and was a historian at the State Department. The opinions expressed are solely that of the author and do not express those of the U.S. government. This article was originally published in March 2015.

Story highlights

Sport brings together kids from different backgrounds in France

The country's demographic has changed since decolonization

Government policies encouraged greater sports participation

Cultural attitudes towards sport, and football in particular, remain problematic

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, the idea of liberté, égalité, fraternité in France might have seemed irretrievably fractured. But try telling that to the thousands of kids and teenagers playing football in the Paris ?le-de-France region week-in and week-out.

Football is one area of French life where the nation’s founding principles are very alive and kicking.

With a population of 12 million, the Ile-de-France - also known as Région Parisienne (Paris Region) – is bigger than some European countries and in Chatenay-Malabry, a town 12 kilometers south of Paris, the football section of the local sports club, ASVCM, serves as a hive of activity.

It accepts young players of any level in its football school and fields several competitive teams. Membership is diverse and reflects the club’s location in a Zone Urbaine Sensitive (ZUS,) an urban area designated as a policy priority to help alleviate its difficult socio-economic conditions. “For us,” noted Marc Girard, the football section’s president, “it is a kid and a ball.”

Some families encounter difficulties paying membership fees due to parental unemployment. Yet, the club does all it can to facilitate youth participation. The aspiring footballers are there, after all, for their enjoyment of the sport.

They’re also there to learn. Beyond teaching technical skills, the club instills concepts of punctuality, respect, fair-play, and tolerance.

“A football club like ours,” said Girard, “we work very much on education and citizenship.” In French, “éducation” can also mean “upbringing.”

Throughout the country, local football clubs serve both senses. “It’s true that we have a social responsibility,” Girard said of Parisian-area football clubs, which constitute the nation’s most populous league.

As a journalist for Canal + and president of sports think tank Sport & Démocratie (which the author is also a member of), Sylvère-Henry Cissé is intimately familiar with this educative role.

“Through football,” he said, “sport is the third means of socialization after school and the family.”

It can also potentially instill the values of democracy, teamwork, playing by the rules, and success based on merit. “Sometimes it is the second means of socialization,” added Cissé, “when the family cannot, or does not have the time or means to participate in socialization.”

Following the January attacks, Cissé noted, “we immediately sought solutions in sport, to understand where sport had failed.” Even if sport didn’t fail in socializing the three young men who committed the atrocities. Society did. After all, as Cissé emphasized, “sport is just a reflection of society.”

France has changed vastly over the past 50 years, a shift the sports world mirrors. It has always served as a destination for immigrants.

Patrick Mignon, a sociologist at INSEP, the national sports institute (Institut National du Sport, d’Expertise, et de la Performance), noted that until the 1960s, “France was a very white society.” Most who emigrated originated from all corners of Europe and assimilated seemingly seamlessly into the social fabric.

Decolonization, however, and the aftermath of the Algerian War changed the demographic. North Africans had long resided in France, but arrived in far greater numbers after 1962, as did Sub-Saharan Africans and French Antilleans. Most sought economic opportunity. France offered better paid jobs and their labor fueled the booming postwar economy.

Then the 1973 oil crisis hit and brought inflation, unemployment, and xenophobia. Racism reared its ugly head and the ascendant far right wing Front National began to question just who, exactly, was “French.”

Newcomers caused consternation, as did the baby-boomers of the 1960s. Youth’s disinterest in athletics fed the era’s sports crisis, a lack of medals and victories at international competitions.

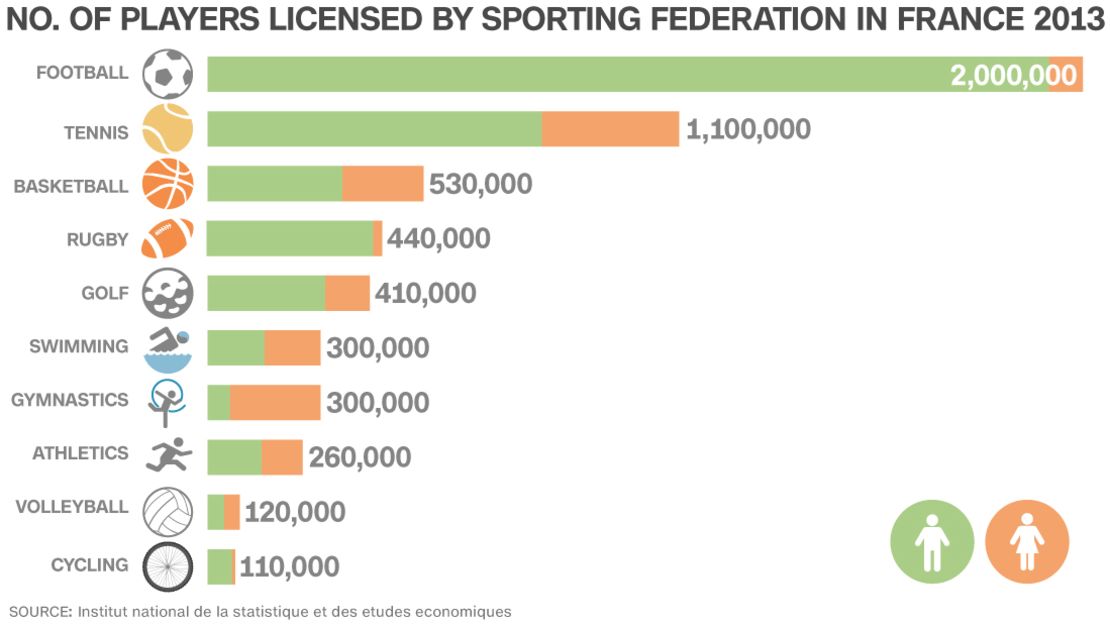

Subsequent government policies encouraged greater sports participation, and the 1975 Mazeaud Law legislated a place—and funding—for sports within the national culture. Since then, athletics are increasingly a tool for social insertion and football leads the way.

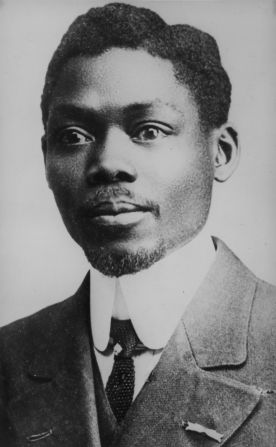

For Cissé, the intersections of assimilation and football are personal. His great grand-uncle, Blaise Diagne, was the first black African deputy elected to the French parliament. Diagne’s son Raoul was a talented, highly regarded footballer for famed Racing Club de Paris. Raoul became the first black player for the national team in 1931, and was welcomed by the public and press.

Both Diagnes were successful because of their talent, but it wasn’t easy. They constantly had to be one-and-a-half or two times better than everyone else to demonstrate their merit. “That is tiring,” Cissé said, “and after a while, it’s discouraging.”

Eighty years later, sport remains an arena where anyone can participate. Across the country, kids from all backgrounds play together. They learn to excel regardless of skin color, family origins, or religious background.

Such was the case for Farid El Alagui, who now plays for Scottish club Hibernian.

“I never felt anything, any difference, from the way that people were looking at me,” he recalled of his youth in Marmande, near Bordeaux.

Born to parents who emigrated from Morocco in the early 1970s, El Alagui grew up near the football stadium and played for local club FC Marmande 47. He enjoyed football as a youth in the early 1990s, the camaraderie it offered, and sense of community.

“I think it helps a lot for you to not be by yourself and excluded by others,” he said.

Football plays the same role today, but the constant lure of the Internet and social media complicate the situation. Some kids become socially isolated from their peers the more they become involved in the online world. For El Alagui, football is an antidote to this seclusion.

It also serves as a social lubricant. “Sharing the same passion and the same sports definitely helps a lot to be more involved in society,” he said.

And in France, the most common sport is football. “For every kid,” El Alagui went on, “the first ball we kick is a football.” Most athletes, regardless of their discipline, played football as young children, including basketball players Nicolas Batum and Kévin Séraphin.

Yet, cultural attitudes towards sport, and football in particular, remain problematic.

France does not have a national sports culture akin to that of the United Kingdom or the U.S.. French cultural elites and opinion makers traditionally disdained football as a working-class sport.

Consequently, public discourse has historically criticized it, particularly when the national team fares poorly at international competitions.

Such snobbism may be related to football’s legacy as the first team sport to professionalize in the early 1930s. The mercenary nature of the professional game rankled a country that long clung to the Olympian ideal of amateurism.

And old habits die hard. According to Christian Gourcuff, the French coach of the Algerian national team, France still lacks a high respect for football.

Inroads were made when the country hosted and won the 1998 World Cup and the sport’s popularity, especially within youth culture, was bolstered.

“There was a lot of pride among the French with this title,” Gourcuff observed. It was an important turning point, though Gourcuff emphasized, “the French are not connoisseurs of football like the Spanish or Italians.”

The 1998 experience built national solidarity around the black-blanc-beur team. For former player and ex-Paris Saint-Germain official Jean-Michel Moutier, “the true value of sport is that everyone is there thanks to their talent and work.”

The white, black, and Arab players that year embodied this notion. They were hailed as a positive representation of a multi-ethnic France and it seemed that sport had much to teach society.

Television and media have since bolstered the game’s popularity and amplified its pervasiveness. The influx of money into professional football from sponsors, television contracts, and foreign investors has made being a footballer attractive to many youths. Traditional careers in medicine, law, and public service pale in comparison.

The route to a métier (professional career) in football is through the professional clubs’ youth academies, which claim to focus on athletics, academics, medical supervision, and citizenship. Today these formation centers are filled with aspiring players whose parents or grandparents immigrated to France from Africa.

For the boys, it is a chance to realize a dream. For their families, however, football is a way for their sons to survive.

“It is much more difficult to be promoted socially though work or school,” said Mignon, than through sport. Thus, “sport is a means for people of immigrant background to not only integrate into society, but to have some rewards.”

If successful, the payoff can be large. But Moutier threw caution to the wind. “Often,” he said, the academies “take youths too young.” The problem comes when the player does not evolve well, fails to sign a professional contract, and is let go.

“Then he is put in a position of failure,” Moutier said, “and that is not good for society. Sport needs to pay attention to keep its true values.”

Despite that dark side, football remains one of the most inclusive and egalitarian milieus.

According to Moutier, this is because “one needs everyone else” in order to win. “There is sincerely no discrimination,” he said.

Gourcuff agreed. “Frankly, there is no [discrimination],” he said. “There are fewer problems of discrimination within football than in society.”

Such egalitarian claims are sometimes tested.

Last fall, Bordeaux coach Willy Sagnol was taken to task for comments about African players, who he deemed more powerful, albeit less disciplined and intelligent than others.

The former French international insisted his words were misinterpreted, that he spoke about on-field intelligence, not player IQ. Critics disagreed and cited the offensive nature of his remarks.

The incident illustrated that football may be equal in practice, but not in politics.

“The problem,” Mignon observed, “is not at the level of playing, but at the level of managing sport.” Today there are many coaches from diverse backgrounds, but the football hierarchy remains the domain of older white men. One of the exceptions is Jamal Sandjak, president of the Ligue de Paris Ile-de-France de Football, whose family has roots in Algeria.

Football is not singular in this regard, but handball is an instructive exception. The national men’s team, Les Experts, won the World Championship in late January, a victory that helped national healing.

The team is often cited as a good representation of France as the federation recruits from diverse pools of talent.

According to Cissé, former handball player Didier Dinart, who is from Réunion, is on track to possibly become Les Experts’ next head coach.

“Here is someone who is an example,” Cissé said, especially for youths. “A French person, whether they are white, black, or Arab, could say, ‘I have an example I can follow.’”

While handball may be exemplar, it does not have the same reach as football.

El Alagui emphasized the ease of playing football, even for those without financial means. Football can be played in the streets; one doesn’t have to belong to a club.

“I haven’t seen any kids by themselves playing handball in the street,” he said.

“Football is a leader,” agreed Mignon. With clubs in most cities and towns nation-wide, he pointed out, “football is everywhere.” Moreover, as these clubs are open to all, Mignon noted, “you don’t need to have ethnic clubs to promote sports.”

In late January, Secretary of State for Sport Thierry Braillard launched an appeal to sports clubs nationwide. He asked them to use their expertise to help improve social ties in the attacks’ aftermath.

For football clubs in particular, with their extensive, extended networks and deep involvement in some of the nation’s disadvantaged communities, there are great hopes.

Last Friday, the government called sport to national service. The announcement of new measures aimed at improving the social malaise highlighted by the January attacks included a “citizens of sport” component.

The program seeks greater provision for and access to sports facilities in underserved areas. It also encourages sports federations to help train citizens – their young athletes.

The hope is that football, and sports more broadly, can help France’s varied communities to feel more included, less ostracized.

As a French Muslim El Alagui is well positioned to speak about such difficulties. “We love France a lot and this is a great country to live in,” he said.

“France and French-Muslim people [are like] an old couple who has forgotten they used to live well together for many years.

“The communication between each other has been really bad, and both sides camp on their positions. One side has to go towards the other to re-open constructive talks.”

After the January attacks, he emphasized, “it is important to try and manage to find a way to re-learn how to live together again in France.”

But can football serve in this capacity?

“Sport is only an instrument,” stressed Cissé. “Sport is akin to nuclear power. If it is used well, you make electricity.”

But, he cautioned, “if it’s misused, you make bombs. For sport to be well used, it is necessary that coaches and volunteers who occupy themselves with our children are also well formed.”

On Thursday, read Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff on why French football struggles to attract and retain girls

!["We love France a lot and this is a great country to live in," said French Mulsim Farid El Alagui who now plays for Scottish club Hibernian. He added: "France and French-Muslim people [are like] an old couple who has forgotten they used to live well together for many years."](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/150309123202-farid-hebdo.jpg?q=w_2444,h_3059,x_0,y_0,c_fill/h_447)