Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

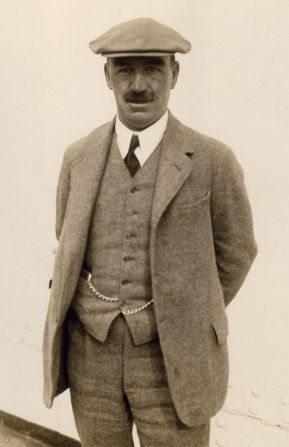

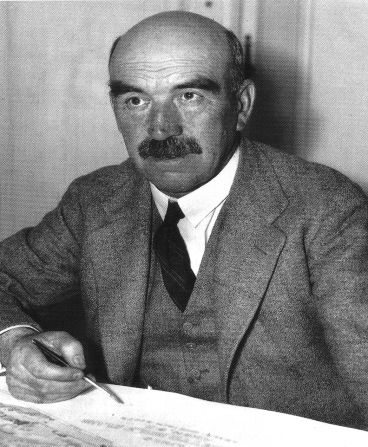

Alister MacKenzie, a physician turned golf architect, designed famed Augusta National course

The Scot was enlisted to help by Bobby Jones, a multiple golf champion of the 1920s

MacKenzie never received full payment for his work and died before first Masters was held

Many of his design principles still permeate the course despite many changes over the years

“Can you possibly let me have, at any rate, five hundred dollars to keep us out of the poor house?”

These are not the words you expect to hear from a man who designed one of the world’s most famous golf courses.

Dr. Alister MacKenzie, the brains behind Augusta National’s revered contours and curves – elegantly showcased each year by the Masters – died pleading poverty in 1934 and begging for his fee.

He never even saw his finished work before his death, which came less than three months before the first Masters tournament was held.

“I have been reduced to playing golf with four clubs,” he wrote in a letter to Augusta National, recorded in “The Making of the Masters,” a book by David Owen commissioned by the club.

“I am at the end of my tether, no-one has paid me a cent since last June, we have mortgaged everything we have and have not yet been able to pay the nursing expenses of my wife’s operation.”

MacKenzie, a physician turned golf architect, had embarked on a pilgrimage that had taken him from a modest town in northern England to the pacific coast in California.

His journey incorporated a stint in the Boer War, which influenced his underpinning principles of course design, and saw his work evolve during the boom and bust years of the 1920s.

By the time he was enlisted to build a championship course for all of America by its biggest sports star of the age, MacKenzie was the preeminent golf architect of his time.

Bobby Jones had won the grand slam as an amateur in 1930 – capturing all four major tournaments in the calendar year – before he stunned the public by announcing his retirement aged just 28.

He determined to construct an exclusive golf course in the sun-blushed south of the United States that would offer him twin benefits: sanctuary from his fame and a healthy stream of income.

But though Jones declared himself delighted with the finished product, and its architect trumpeted Augusta as his finest creation, MacKenzie was almost destitute by the time he died.

He halved his fee to $5,000 in a bid to be paid quickly, but clawed back just $2,000, with several other golf courses also slow to settle their debts.

It was symptomatic of the financial difficulties Augusta encountered in its fledgling years, exacerbated by the Great Depression, a fact that seems inconceivable given the club’s towering strength in the present day.

“Augusta struggled a lot in the early years and found it very hard to attract members they wanted,” Adam Lawrence, editor of Golf Course Architecture magazine, told CNN.

“They were really struggling for money. MacKenzie didn’t get full payment paid for his work at Augusta – until he died he was writing letters asking perhaps they could send part of the fee.

“MacKenzie divorced his first wife and was living what would appear to be an expensive lifestyle in California. He was basically bankrupt when he died.

“There were a lot of golf architects from that time who were the same. Most seemed to be terrible businessmen and there were a few bad habits like too much booze flying around.”

Humble beginnings

MacKenzie’s portrait still watches over the course where his maverick design ideas were first put into practice over 100 years ago.

Despite the odd tweak, Alwoodley Golf Club – just outside the city of Leeds in the north of England – still boasts many of the original characteristics conceived by the Scot.

As Nick Leefe, secretary of the Alister MacKenzie Society, told CNN, the physician’s long-held affection for the game even permeated some of his diagnoses.

“How frequently have I, with great difficulty, persuaded patients who were never off my doorstep to take up golf, and how rarely, if ever, have I seen them in my consulting rooms again!” MacKenzie is reported to have proclaimed.

This love of golf sparked an interest in course architecture after a period serving during the Second Boer War, between the British and the South African Republic, at the turn of the 20th century.

“The attitude of the Boers towards camouflage got him interested in disguise and trickery,” Leefe explains. “People suggest this is the reason he came back after the war and took an interest in golf design.”

When a group of businessman joined together in 1907 to build Alwoodley, MacKenzie presented his designs and had them rubber-stamped by Harry Colt – another famed architect of the age who worked as a consultant on the project.

MacKenzie’s fundamental belief was that a good golf course should provide a stern test for a good player but not prove impossible for average players.

Also included in his manifesto was an insistence that a player should be required to utilize a variety of shots to prosper and that every hole should have a different character where possible.

Among the more eccentric attributes listed was the suggestion that though the course should be sufficiently undulating, there should be no hill climbing, and that a complete absence of irritation caused by looking for lost balls was preferable.

“Alwoodley is very proud indeed because we have the original MacKenzie design and we are very proud to introduce people to it,” Leefe says.

“MacKenzie was a pioneer and went on to become one of the best known architects of his time. He’s become much more famous after his death and the golfing public have realized what great courses he’s made.

“There are a lot of the original MacKenzie characteristics on show at Alwoodley. We try our best when we restore the course or renovate course to keep to the original design of which we have a copy.”

Augusta National

MacKenzie had carved a formidable reputation for himself by the time he left for the United States in 1926.

But it was his work on the Californian coast that would pique the interest of Bobby Jones and lead to his most memorable tender – designing Augusta National.

Many believe MacKenzie’s true masterpiece to be Cypress Point, which he designed to complement its proximity to the rugged Pacific Ocean coastline.

By the time Jones had completed his first round on the Monterey Peninsula he vowed to employ MacKenzie to build his very own course.

It seemed the logical choice, given how closely their vision for the ideal golf course was.

“We believe that no good golf hole exists that does not afford a proper and convenient solution to the average golfer and the short player, as well as to the more powerful and accurate expert,” Jones was reported as saying.

But by the time $100,000 had been spent transforming an Augusta fruit plantation into a golf course, the political and financial landscape had changed dramatically thanks to the stock market crash of 1929.

The exuberant flourishes on show via a series of elaborate bunkers at Cypress Point and another of MacKenzie’s fabled courses – Royal Melbourne in Australia – gave way to a more modest design in which contour was king.

“Originally, Augusta was light on bunkers – it has many more today than it used to have,” says Lawrence. “Augusta was one of the very last things MacKenzie did before he died and it seems he was moving away from those flashy bunkers.

“He was working in a style that was appropriate of the era of depression when Augusta was built. It wasn’t about sand or water – what defined it were the contours of the land.

“You can take a flag stick and put in a flat area and it’s a very easy golf hole; you can put it behind a little hump and it’s an almost impossible golf hole.”

The genius of Augusta

In those early years of struggle, the notion of Augusta preparing to host the 78th installment of the Masters in 2014 would have seemed quite fanciful.

As Owen reports in “The Making of the Masters,” let alone having the funds to pay MacKenzie for his design, the club could barely cover its staff’s $200 weekly wage bill in the early 1930s.

The idea to create a yearly tournament, initially called the Augusta National Invitational Tournament, helped stave off the threat of financial ruin and generated plenty of interest when Jones came out of retirement to play in the first one.

But what really catapulted the club into the public’s consciousness was Gene Sarazen’s “shot heard around the world” during the 1935 event.

The American was trailing the leaders by three shots when his double eagle on the par-five 15th hole helped him cut the deficit with one stroke, paving the way for his eventual win in a playoff.

That landmark moment is testament to the principals upon which MacKenzie’s design was built.

Various tweaks over the years have stripped many of his original features from the course, most of them dictated by the modern player’s ability to hit the ball over a hundred yards further than their predecessors.

But as Owen wrote: “MacKenzie’s and Jones’ ideas about golf course design continue to define the Masters in ways that modern golf fans may not fully appreciate.”

The pair’s commitment to break from the culture of golf design at the time – which penalized poor shots harshly – has engendered some of the greatest finishes in major golf.

As Owen makes clear, the plentiful birdie and eagle opportunities down the closing stretch discourage any conservatism, as anyone in with a sniff of winning charges for the finish line.

But it’s not just at Augusta that MacKenzie’s legacy is felt – an estimated 100 clubs as far afield as Buenos Aires and Blackpool have been touch by his hand.

“MacKenzie is undoubtedly one of the most important figures in terms of the evolution of golf course design,” Lawrence says.

“Augusta, Cypress Point and Royal Melbourne are three courses that would typically be in the top 10 in the world in most rankings, and the fact all three courses have MacKenzie’s footprint is pretty impressive.”

MacKenzie may be long gone, but he lives on in the soul of golf courses the world over.